October 22, 2022 – February 19, 2023

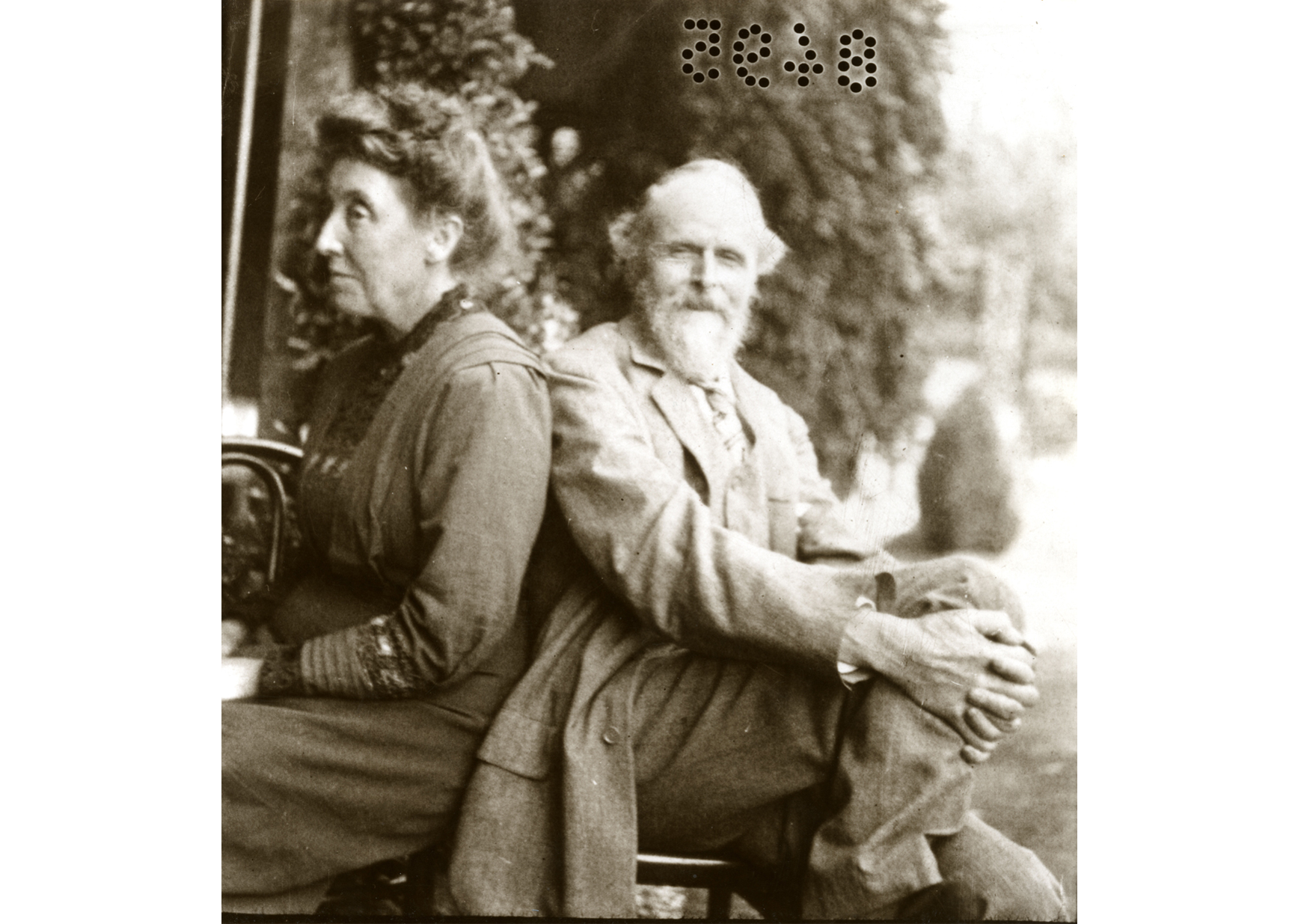

This fall the Museum will host the first retrospective exhibition of the work of Pre-Raphaelite painter Evelyn Pickering De Morgan (1855-1919) and her husband, the stained glass and pottery designer William Frend De Morgan (1839-1917) [FIG. 1 above]. The two artists met and married in 1887 after both were well-established in their careers. As a couple, their work touched on several influential artistic circles of the day including the Pre-Raphaelite, Arts and Crafts, and Aesthetic Movement. More broadly speaking, their individual and shared political and social views put them in connection with circles outside the art world – among others, socialists, suffragists, and pacifists — with the result that their combined reach within Victorian society and culture was quite broad —even comprehensive. And yet, they have received relatively passing recognition —William perhaps because he was a craftsman, a genre which has historically taken a back seat to fine arts, and Evelyn because of her gender. She was in fact often written off as simply a disciple of Edward Burne-Jones, a painter with whom she had very little if any professional relationship. Addressing the two artists within one exhibition allows for a comprehensive view of the expanded cultural milieu in which they functioned, not least regarding new attitudes towards Victorian marriage as a working partnership.

William De Morgan

William was born in 1839. His mother, Sophia, was a writer, activist, and an important figure in the spiritualist movement. His father, Augustus, was a mathematician and logician who taught at the newly founded University College, London. William shared his father’s facility for mathematics but was determined to pursue a career in the arts. Originally intending to be a painter, he enrolled at the Royal Academy Schools in 1859. There he met many members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle through whom he was introduced to William Morris around 1863. This was the moment that Morris’s newly founded decorative arts partnership, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., was finding success in the fitting out of newly built Gothic Revival churches, particularly with stained glass. William De Morgan began designing in this media. His lifelong inclination for experimentation led to improvements in the firing of stained glass, an interest that undoubtedly inspired his turn to pottery making.

In 1869, William De Morgan began his own pottery firm, focusing on the production process and the design of the decoration. His designs reflect his absorption of varied sources, including Pre-Raphaelite medievalism, Italian Renaissance maiolica, and ancient Middle Eastern lusterware [FIG. 2]. Additionally, his decorations feature a menagerie of anthropomorphized creatures that were the product of his own vivid imagination [FIG. 3]. Unfortunately, despite his acumen for invention and his facility for design, he was not a businessman. The pottery was never financially viable – in fact, Evelyn may have contributed to keeping it afloat during the early portion of their marriage – and by 1907 he decided to close the pottery business.

Evelyn Pickering De Morgan

When Evelyn Pickering was born in 1855, William was 16 years old and at the very beginning of his professional career. Evelyn’s family straddled the upper middle class and aristocracy. Her father was a London lawyer and Queen’s Counsel; her mother was a descendant of the 1st Earl of Leicester. Evelyn’s artistic inclinations were evident early on, and despite familial resistance, she insisted on pursuing an artistic career. She was assisted in dodging her mother’s opposition by her uncle, late Pre-Raphaelite painter John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829–1908), who had experienced similar opposition to his career choice. “Uncle Roddy” offered both mentorship and artistic tutoring.

In 1873 Evelyn was accepted at the newly opened Slade School of Art. The Slade offered one of the few opportunities for women to receive artistic training, and it was there that Evelyn’s mature style was nourished. Specifically, The Slade offered a rigorous program focused on drawing from the figure, and female students were permitted to draw from the live model. Evelyn’s education was further enhanced through continental travel, providing access to historic works of art, particularly those of the early Italian Renaissance, the touchstone of her mature style. Several watercolor copies of Renaissance paintings confirm her close study of the art of this period. In images like Flora [FIG. 4] we can see her borrowing from Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera.

Evelyn began her exhibiting career in 1876, showing first at the Dudley Gallery, a small outpost of avant-garde and early career artists. In 1877 she was one of only two female artists invited to exhibit at the inaugural exhibition of the trendy new Grosvenor Gallery, an avant-garde outpost for the Aesthetic Movement. This was a milestone in her career, indicating her professional success.

Willam & Evelyn’s shared passions

In 1883 William and Evelyn, who had for the last decade been travelling on parallel but separate tracks, came together. In addition to art, they were particularly committed to three causes — Victorian spiritualism, the early efforts of the women’s suffragist movement, and pacifism in response to the overwhelming devastation of the First World War. Many of Evelyn’s paintings reflect these concerns, for instance, The Gilded Cage [FIG. 5], depicting a beautiful young woman gazing wistfully out of the window of her richly furnished home at a group of revellers. At right, her aging husband slumps dejectedly in a chair. The scene conveys the constraints of being a woman in a traditional Victorian marriage. In The Worship of Mammon [FIG. 6], inspired by a story from the New Testament, the god of worldliness, a giant stone statue holding a bag of coins, is approached by a female figure who desperately clutches at his knee. The economic disparity of the ear distressed William and Evelyn.

The De Morgans lived well beyond the Victorianism and Pre-Raphaelitism of their youth. This included the last and particularly bloody expansion of the British Empire and the First World War. The Red Cross [FIG.7] depicts Christ being carried heavenward by a team of angels, while beneath a field of crosses litter the Belgian landscape — a direct reference to the extreme and extensive loss of lives brought about by the war.

US debut of De Morgan exhibition

Evelyn and William De Morgan’s art will be on display in the exhibition A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan, which makes its US debut at the Delaware Art Museum this fall. Drawn entirely from the collection of the De Morgan Foundation in Guildford, UK, I have been planning the exhibition for five years with co-curator Sarah Hardy, Curator, De Morgan Collection. Paintings, drawings, and pots by this artist couple will be featured.

The exhibition will travel on to two further venues: the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA (17 September, 2023-7 January 2024) and the Museum of Fine Arts St Petersburg, FL (27 January 2024 through May, 2024). A publication of essays will accompany the exhibition: Margaretta S Frederick, ed. Evelyn & William De Morgan: A Marriage of Arts & Crafts (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022). The catalogue will be available at the Museum Store later this year.

Margaretta Frederick

Annette Woolard-Provine Curator of the Bancroft Collection

Top: Figure 1: William and Evelyn De Morgan, undated archival photograph. De Morgan Foundation.