Enslavement, Education, and Freedom

Absalom Jones was born enslaved in 1746 on “Cedar Town” plantation in Cedar Creek Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware. Abraham Wynkoop, a wealthy Anglican justice of the peace and assembly delegate, owned Cedar Town. Wynkoop’s grandfather emigrated from Holland to New Netherland (New York) in the 17th century. Abraham Wynkoop moved to the southern-most of the “Lower Counties” in the 1730s. Abraham saw Absalom’s intelligence and had him work in the house. Absalom sought instruction, saved money, and bought books including a Bible. Abraham Wynkoop died in 1753. Benjamin, his middle son, inherited Cedar Town.

Benjamin Wynkoop sold Cedar Town and Absalom’s mother and siblings. In 1761, Wynkoop brought Absalom to Philadelphia, joined St. Peter’s Anglican Church, and became a prosperous merchant. Wynkoop permitted Absalom to attend a Quaker-run night school for Black people founded by abolitionist Anthony Benezet. Absalom’s mathematics education was useful in Wynkoop’s store which sold European cloths. Benjamin Wynkoop married into a prominent Anglican mercantile family.

In 1770, with their enslavers’ permission, Absalom Jones married Mary Thomas. Mary was enslaved to St. Peter’s parishioner Sarah King. Absalom, and his father-in-law John Thomas, purchased Mary’s freedom with donations and loans primarily from Quaker abolitionists. Absalom and Mary repaid the borrowed money, saved more money, and bought property. The British briefly occupied Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War. The Wynkoop family went to Dover, Delaware staying with Mary Wynkoop Ridgely. The Wynkoops worshipped at Dover’s Christ Church. Absalom oversaw the Wynkoop store and house. Although Wynkoop refused, Absalom kept asking to buy his freedom. Absalom persisted because Wynkoop could take his money and property. In 1784 Benjamin Wynkoop manumitted Absalom and paid him for his services.

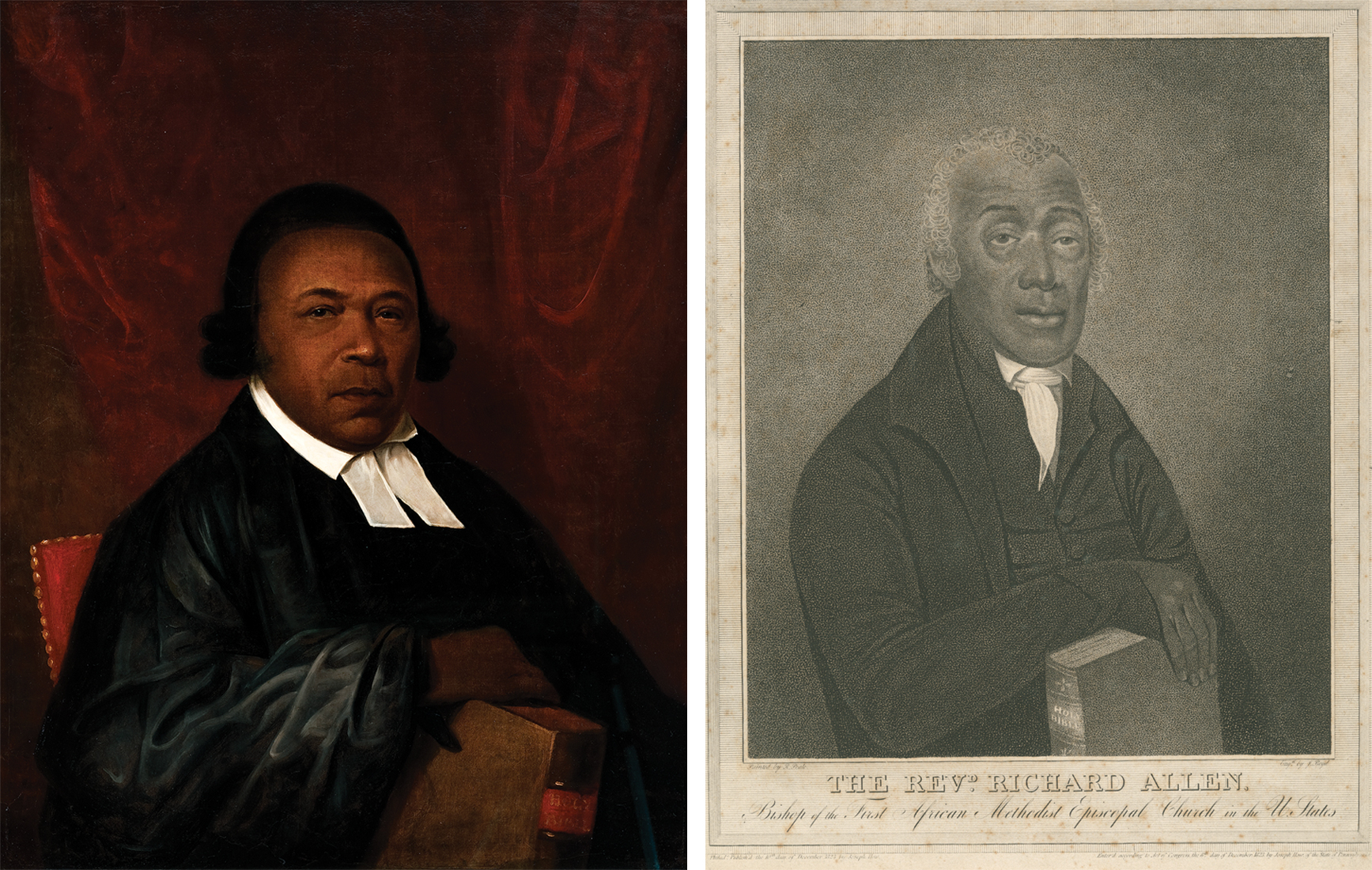

Left to right: Absalom Jones, 1810. Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825). Oil on paper mounted to board, 30 x 25 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Absalom Jones School, 1971. The Revd. Richard Allen, 1823. John Boyd from a painting by Raphaelle Peale. Stipple engraving, 16 x 11 1/2 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Left to right: Absalom Jones, 1810. Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825). Oil on paper mounted to board, 30 x 25 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Absalom Jones School, 1971. The Revd. Richard Allen, 1823. John Boyd from a painting by Raphaelle Peale. Stipple engraving, 16 x 11 1/2 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Founding of the Free African Society with Richard Allen

Absalom Jones started attending St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church. He met Richard Allen, who had also been enslaved in Delaware. They became lifelong friends. In 1787, they founded the Free African Society (FAS), the first mutual aid society organized by Black people. W.E.B. DuBois called the FAS “the first wavering step of a people toward organized social life.” FAS members paid monthly dues to benefit those in need. Jones and Allen were class leaders and lay preachers. The membership increased. They helped raise money to build a gallery. One Sunday morning in 1792, Jones, Allen, and other Black worshippers were directed to the gallery. Absalom knelt and starting praying, but ushers told him to move. He refused, and an usher attempted to physically move him. The prayer ended. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen led most of the Black members out of St. George’s in protest.

Yellow Fever

The FAS, assisted by Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, started the African Church of Philadelphia. The devastating 1793 yellow fever epidemic interrupted their work. Initially, Dr. Rush, a prominent physician, thought Black people were immune to the virus. He appealed to Absalom Jones and Richard Allen to help stricken White Philadelphians. There had been other yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia. It is doubtful that Jones and Allen believed Rush’s immunity theory. No one knew that the virus was spread by infected mosquitoes. Rush trained Jones and Allen to treat patients, and they trained Black nurses. Other FAS members buried the dead. Black Philadelphians proved equally susceptible to the virus. Fall’s colder weather killed the mosquitoes. The epidemic ended. Over 4,000 people perished. Matthew Carey published an account of the epidemic that accused Black nurses of stealing and extorting money. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen published a refutation.

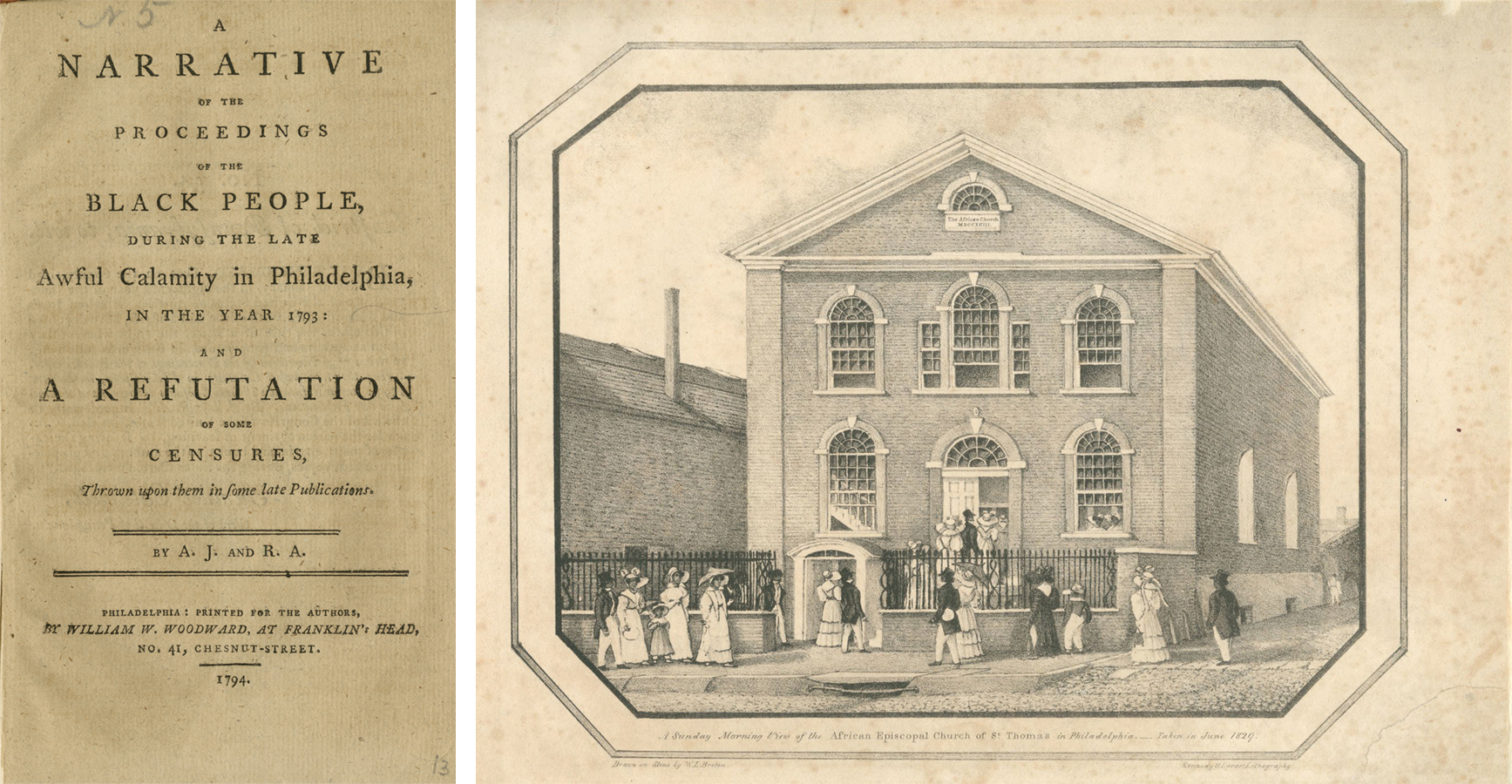

Left to right: Title Page, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, 1794. Absalom Jones (1746–1818) and Richard Allen (1760–1831). Library Company of Philadelphia. A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, 1829. Kennedy & Lucas from a drawing by W. L. Breton (c. 1733–1859). Lithograph, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Left to right: Title Page, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, 1794. Absalom Jones (1746–1818) and Richard Allen (1760–1831). Library Company of Philadelphia. A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, 1829. Kennedy & Lucas from a drawing by W. L. Breton (c. 1733–1859). Lithograph, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas

The African Church affiliated with the Episcopal Church. Richard Allen favored the Methodist tradition, and he organized the African Methodist Episcopal denomination. Absalom Jones agreed, after prayerful reflection, to provide pastoral leadership. The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas was dedicated on July 17, 1794. It applied to join the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania on conditions that guaranteed self-determination but ceded participation in diocesan governance.

Absalom Jones and others explained the church’s founding: “[W]e arise out of the dust and shake ourselves, and throw off that servile fear, that the habit of oppression and bondage trained us up in.” In October 1794, The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas was admitted to the diocese and incorporated in 1796. Bishop William White ordained Absalom Jones a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

Abolitionism

Absalom Jones knew Boston’s African freemasonry founder Prince Hall. Jones became Pennsylvania’s first African masonic Grand Master. In 1799, Absalom Jones and others petitioned the President and Congress to abolish the transatlantic slave trade and slavery. The petition asserted, “If the Bill of Rights or the Declaration of Congress are of any validity, we beseech that … we may be admitted to partake of the liberties and unalienable rights therein …. ” On January 1, 1808 The Rev. Absalom Jones delivered a “Thanksgiving Sermon” celebrating legislation prohibiting the transatlantic slave trade. Rev. Jones preached that “[God came] down to deliver suffering [Africans] from the hands of their oppressors … when … the constitution [mandated] that the [African] trade… should cease … [and] … when [legislation was passed] outlawing the slave trade. [T]his day [we] … offer up our united thanks.” The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas formed a school and was active in moral uplift, self-empowerment, and anti-slavery efforts.

Rev. Jones’ Legacy

Absalom Jones died February 13, 1818. He bequeathed Raphaelle Peale’s 1810 portrait to his nephew George Jones. The portrait made its way to the Absalom Jones School in Delaware and was later donated to the Delaware Art Museum.

Absalom Jones’ achievements are commemorated on three Pennsylvania state historical markers. Delaware’s state historical marker honoring Absalom Jones is in Milford. Absalom Jones was featured in the 2013 exhibition “Forging Faith, Building Freedom: African American Faith Experiences in Delaware, 1800-1980,” organized by the Delaware Historical Society. His story is prominently told in the Smithsonian’s Museum of African American History and Culture. The Episcopal Church recognizes February 13 as Absalom Jones’ feast day. The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas uses Absalom Jones’ altar on his feast day, and his ashes are enshrined in the parish chapel.

Arthur K. Sudler

William Cal Bolivar Director

Historical Society & Archives

African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas