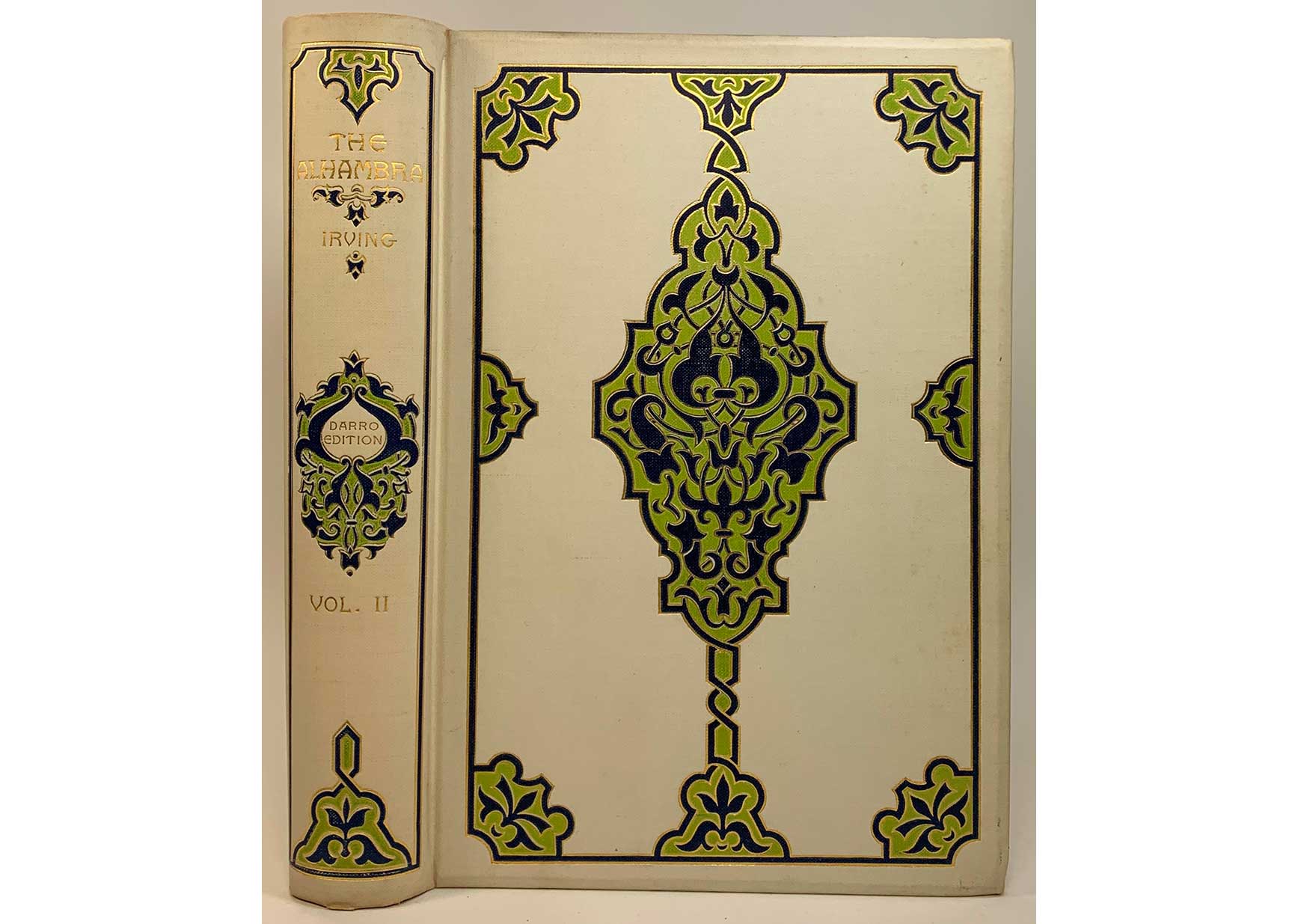

Above: The Alhambra by Washington Irving, cover design by Alice C. Morse (New York: Putnam, 1892) Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Most Americans are familiar with the writer and historian Washington Irving and his well-known legends of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle. Irving (b.1783-d.1859) was one of the first writers from the newly formed United States to be recognized across Europe and he set the standard for a uniquely American form of fiction writing. Less well known are some of Irving’s works of history or his time spent in Europe as part of the diplomatic corps. Two works that came out of Irving’s foreign adventures were histories of medieval Spain during the period when modern day Andalucia was controlled by the Nasrids, the Moorish Muslim Emirate of Granada. Known as The Alhambra and The Conquest of Granada these books remained so widely read that 30 years after Irving’s death they were re-released in revised editions with cover designs by the well-known female decorative artist Alice C. Morse (b.1863-d.1961). Pictured below, both books are a unique look at 19th-century interest in orientalist design.

Irving first came to southern Spain in 1826. His family’s merchant business in New York City had been severely damaged by the War of 1812, and they were no longer able to support his literary career. Hoping Spain would provide him with inspiration for a new book, Irving was given access to both the American consul’s library on Spanish history and the Duke of Gor’s collection of medieval manuscripts. With this source material, Irving compiled his chronicle of the conquest of the Emirate of Granada in the 1480s by Isabella I of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragon. This was the basis of The Conquest of Granada.

Eventually, Irving was given the opportunity to move into rooms at the Alhambra of Granada. This fortified hilltop was the seat of power for the Nasrids, and the location of an elaborately decorated palace from the mid-14th century. It is also arguably one of the finest examples of Moorish architecture in the world. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand chose this location as the site of their own royal court after the conquest. It was here that Washington Irving drew the inspiration for The Alhambra, a series of essays and short stories about the palace structures, their history, legends from the region, and musings about the complex’s current residents. In his preface to the revised edition Irving described it thus, “It was my endeavor scrupulously to depict its half Spanish, half Oriental character; its mixture of the heroic, the poetic, and the grotesque; to revive the traces of grace and beauty fast fading from its walls; to record the regal and chivalrous traditions concerning those who once trod its courts; and the whimsical and superstitious legends of the motley race now burrowing among its ruins.” This content fed the 19th-century West’s growing and ravenous interest in all things “oriental” and “other,” likely leading to the continued reprints of these works after Irving’s death. By 1842 Washington Irving was officially appointed Minister of Spain, due in large part to the contacts he had made in the region 15 years before.

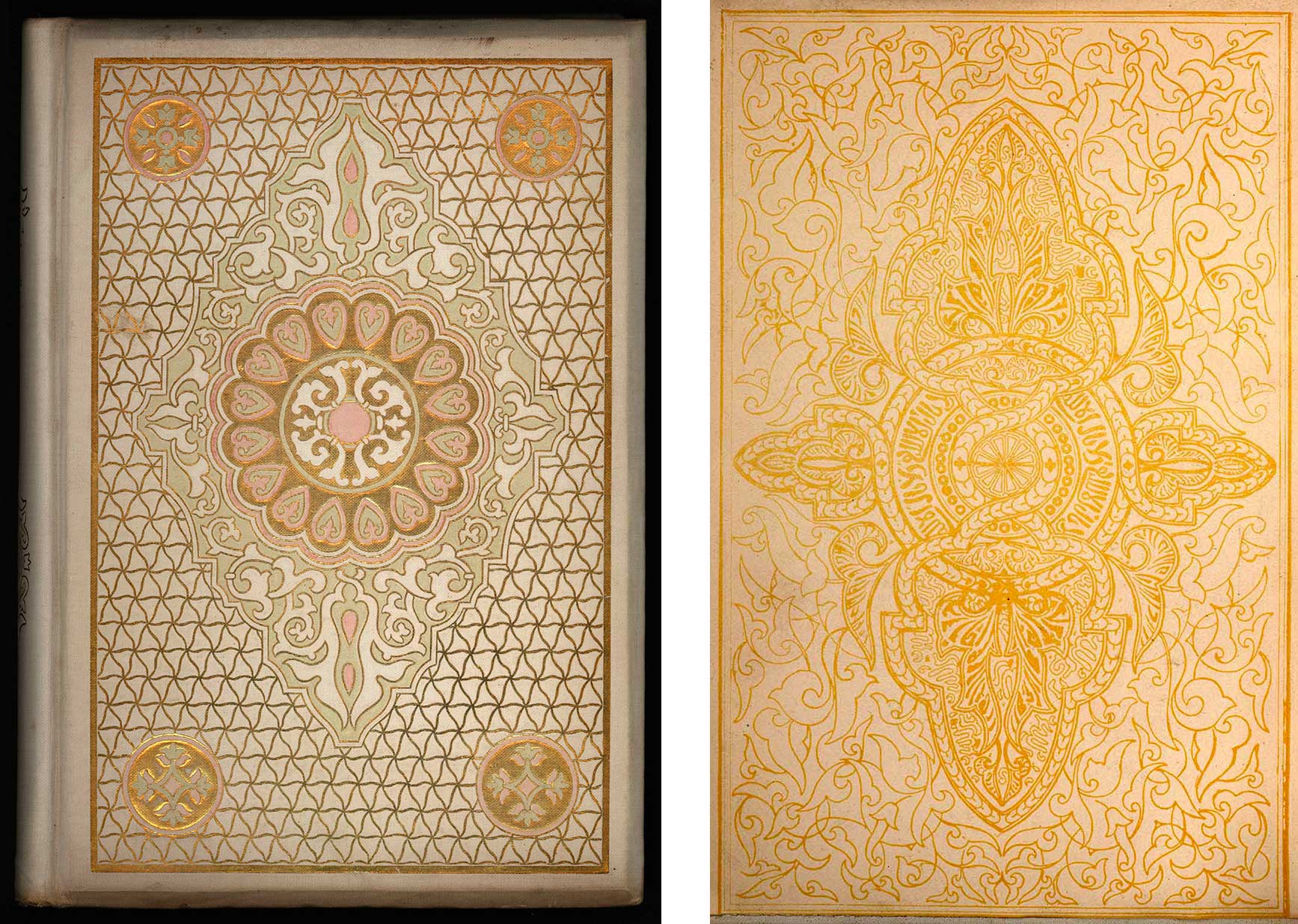

Published in 1892 and 1893 respectively, the revised reprints of Irving’s The Alhambra and The Conquest of Granada were intended as gift-books. Consequently their designs, while simple, are pleasing. They represent the height of book fashion in the 1890s. During the Victorian period dark and rich colors were popular choices for book covers, but by the turn of the century lighter colors of book-cloth grew in popularity. Both covers contain decorative lozenge-shaped fields containing interwoven designs known as “arabesques.” This same style of design-work was carried over into the books’, as shown below.

Above, left to right: Chronicle of the conquest of Granada by Washington Irving, cover design by Alice C. Morse (New York: Putnam, 1893) M.G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. | Endpaper possibly designed by Alice C. Morse from The Alhambra by Washington Irving (New York: Putnam, 1892) Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Above, left to right: Chronicle of the conquest of Granada by Washington Irving, cover design by Alice C. Morse (New York: Putnam, 1893) M.G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. | Endpaper possibly designed by Alice C. Morse from The Alhambra by Washington Irving (New York: Putnam, 1892) Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Many elements of these two book covers betray Alice C. Morse skills and experience as an artist and designer. Morse was trained in the applied arts and their history at the Women’s Art School at Cooper Union in New York City. This institution was tuition-free for any students unable to pay and was dedicated to teaching emerging artists skills and techniques that would ensure them jobs in the field after graduation. Morse was assuredly one of these non-paying students and her time at Cooper Union allowed her to break into a number of the design industries. She spent several years working at the Louis C. Tiffany & Company as a stained glass artist before shifting into regular work designing book covers. Morse found that creating designs for stained glass works was very similar to that of book covers, even if the resulting media differed drastically. Yet, it is clear from her work that Morse was familiar with the artistic processes of production as well. Morse’s book cover designs predominantly involved a creative use of stamping techniques, a process in which heated stamps would be applied to cloth book covers to create designs in relief; the creation of raised and pressed areas. It is likely that Morse collaborated with the engravers who were responsible for executing her designs to create complex effects.

Moreover, the use of arabesque forms on the covers of The Alhambra and The Conquest of Granada indicate Morse’s art historical knowledge. The design of the cover and endpaper of The Alhambra resemble illustrations in Owen Jones’s 1856 scholarly work The Grammar of Ornament. In the introduction to his chapter on “Moresque” or Moorish ornament from the Alhambra, Jones stated, “The Alhambra is at the very summit of perfection of Moorish art, as is the Parthenon of Greek art.” While problematically othering, as Jones made a point of separating Moorish art into a category distinctly separate from Greek art at the center of the Western canon, in the 19th century this work was the foremost authority on ornamental designs for English-speaking audiences. Alice Morse clearly referred to this text when developing her designs for Irving’s two books. In addition to drawing upon some of the illustrations, Morse was well versed in the written descriptions as well. In particular, Jones stated that Moorish ornament was often comprised of primary colors such as blues and reds, along with a predominance of green backgrounds. Further he stated that yellow tones were often expressed with gold. Morse’s designs follow these principles. For example, in the case of The Alhambra Morse has created an interlocking design in blue and gold on a green background. Jones additionally expressed the Moorish interest in constructing geometric forms out of vine-like and vegetal elements. The endpaper for The Alhambra is an example of this concept. The main design resembles two large and two small broad leaf-forms along with four half-leafs all radiating out of a circular center. All around these leaves are a series of regular arabesques that weave between one another like vines. The entire composition is symmetrical and organized in a way that would never occur in nature, although inspired by its forms.

Alice C. Morse applied her design skills to a number of other book covers in the Delaware Art Museum’s collection. An exhibition of this material in the Special Collections Cases located in the lower lobby outside the Library and Kid’s Corner will coincide with the exhibition Louis Comfort Tiffany: Treasures from the Driehaus Collection opening on October 17, 2020. Check back then to learn more about this unique artist.