If you were driving down to the Delaware beaches this past summer, you likely passed by the capital of Dover. However, you may not have known that the State House in Dover holds an impressive work of art by a celebrated African American artist!

In 1924, the artist Edwin Harleston (1882 – 1931) was awarded a prestigious commission to paint the portrait of the Delaware businessman and philanthropist Pierre Samuel DuPont (1870 – 1954). This artwork represents an important instance of interracial collaboration during racial segregation in Delaware, as Harleston, an artist and activist who was then-known as the “leading portrait painter of the [African American] race,” was invited by a group of Black teachers to create a portrait in honor of DuPont’s support for Black education in the state.

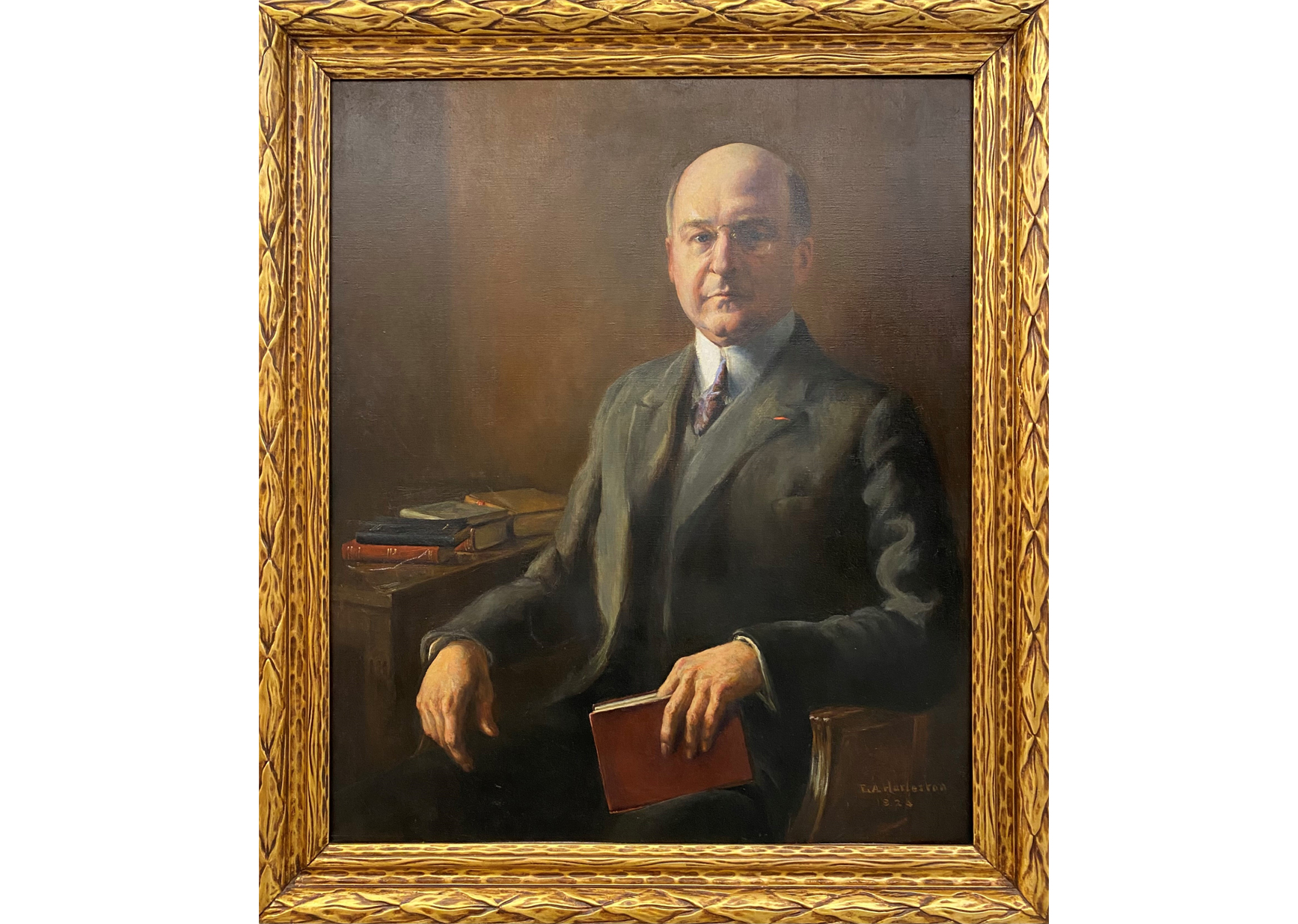

Portrait of Edwin Harleston (1882 – 1931). Courtesy of the College of Charleston

Portrait of Edwin Harleston (1882 – 1931). Courtesy of the College of Charleston

Born in Charleston, South Carolina to a prosperous African American family, Edwin Harleston attended Avery Normal Institute and Atlanta University before enrolling at the prestigious School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. There, Harleston studied with contemporary masters of American painting, including Frank Weston Benson (1862 – 1951) and Edmund Tarbell (1862 – 1938) – as well as William McGregor Paxton (1869 – 1941) and Philip Leslie Hale (1865 – 1931), whose work can be found in DelArt’s collections. The so-called “Boston School” of American painting was concerned with the subtle effects of light on surfaces and the delicate rendering of skin tones. This influence can be seen in Harleston’s masterful use of shadow and a blending of colors to accurately portray the features and skin color of Black Americans (see, for example, Harleston’s paintings in the collections of the Gibbes Museum in Charleston and The Johnson Collection in Spartanburg, SC).

In a 1923 letter to his wife Elise Forrest, Harleston explained the greater meaning behind his artistic practice, as he hoped to carry on the legacy of the pioneering African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859 – 1937) by portraying Black Americans “in our varied lives and types with the classic technique and the truth, not caricatures . . . to do the dignified portrait and…[show] the thousand and one interests of our group in industry, religion, general social contact.” i

For many years, however, Harleston struggled to achieve professional success, as both racial prejudices and familial duty constrained his practice. After completing his studies in Boston in 1914, Harleston was called home to assist in his family’s undertaking business. Still hoping to support his family through his art, in 1922 he and Elise opened an art studio across from the Harleston Funeral Home, where portraits in oil, charcoal, pastel, and French crayon were made available to members of Charleston’s Black community. Elise, a trained photographer, often produced photographs as source material for Edwin’s portraits.

In 1923, Harleston’s star rose following his participation in the annual Negro Arts Exhibit at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, in Harlem. Following the exhibition, Harleston’s painting The Bible Student (1923) appeared on the January 1924 cover of the progressive Black journal Opportunity with an accompanying article declaring that “a man of his genius should most certainly be widely known.” ii

It was in this context that none other than W.E.B. Du Bois, the renowned scholar and co-founder of the NAACP, recommended Harleston to the DuPont Testimonial Association, which was organized to share appreciation for DuPont’s support of Black schools and to “pass on to the country the spirit that has made Delaware public county schools for colored people the best in this country.” iii

As a member of the prominent DuPont family, Pierre Samuel DuPont was seen as the driving force behind the modernization of DuPont Chemical and General Motors and was widely recognized for his role in establishing American industrial pre-eminence around the world. Like many members of the DuPont family, Pierre was also known for his philanthropy. In addition to his stewardship of Longwood Gardens, DuPont spent millions of dollars of his own money to construct and rebuild educational facilities for African American children. In appreciation of DuPont’s support for Black Delawareans during this period of segregated education, teachers of color from throughout the state came together to honor DuPont through the commissioning of a portrait from the country’s leading African American portraitist, Edwin Harleston.

The resulting portrait is unique to Harleston’s practice; in fact, it is the only surviving portrait by Harleston of a white sitter. The work shows DuPont sitting in his office in a three-quarter pose, with his body slightly turned toward the viewer. With his elbows resting on the arms of the chair, DuPont rests a finger of his left hand inside a book – a sign of the importance of education.

As in his earlier works, Harleston’s approach to the DuPont painting is based on the tradition of the Boston school, which includes an interest in the effects of light on surfaces and skin. Harleston has defined DuPont’s figure through the use of strong direct lighting, as evidenced by the high values of light on his face and hands. As one scholar noted, “these areas of high intensity might have been constructed with flat, broad strokes,” but Harleston, building off his skills in rending the subtle of skin tones in Black Americans, has taken great care to model DuPont’s white skin with shadow and subtle variations of color.

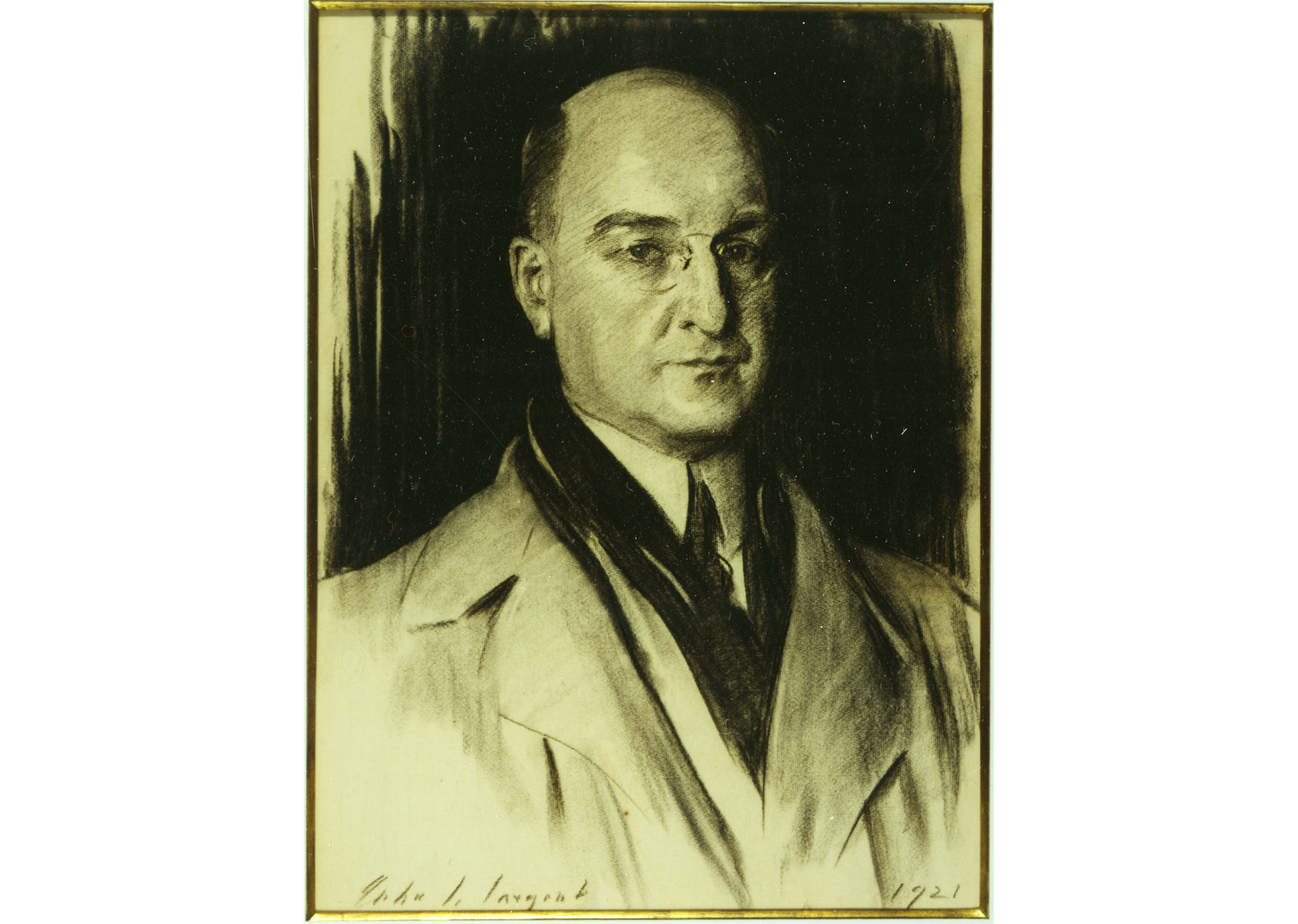

This gradation of tone from light to dark – particularly in DuPont’s face – challenges the viewer to peer carefully into the shadows to see the fine details of his features. And, in fact, DuPont’s wife, Alice, thought that the shadows around the subject’s eyes and mouth made DuPont look stern rather than sensitive. Referencing the portrait of Pierre DuPont done by John Singer Sargent, which is in the collection of Longwood Gardens, Alice remarked that Harleston had “painted the mouth just as Mr. Sargent had done […] giving him two pronounced shadows under the lower lip and making him appear too severe.” iv As one scholar has written, “To be compared with even John Singer Sargent’s errors must have seemed almost complimentary to Harleston.” v But, to please Mrs. DuPont, Harleston later softened the shadows.

John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925). Portrait of Pierre S. Dupont (1921). Image courtesy of Longwood Gardens

John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925). Portrait of Pierre S. Dupont (1921). Image courtesy of Longwood Gardens

When Harleston unveiled his portrait of DuPont to the public at a special presentation at Booker T. Washington High School in Dover on December 5, 1924, both the public and DuPont himself expressed their pleasure with the outcome. DuPont later wrote the artist in gratitude, and informed him that the time spent posing for the artist had been both enjoyable and “worth while.” For the DuPont Testimonial Association, the portrait was an aesthetic triumph and cultural achievement that carried “the race one step higher.” vi Articles praising the portrait appeared in newspapers in New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, and with this project, Harleston finally achieved the national recognition for which he had been striving for most of his life.

Tragically, Edwin Harleston died of pneumonia in Charleston at the age of forty-nine, a promising career cut short. Today, we can see his portraits of African Americans and South Carolina landscapes represented in the collections of the Gibbes Museum of Art, the Johnson College, and the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art. It is in our own state of Delaware, however, that we can see how this “leading portrait painter of the [African American] race” sought to apply his skills in rendering Black skin, to that of a prominent white American and supporter of opportunities for Black Delawareans.

Anne Strachan Cross

2021 – 2023 Lynn Herrick Sharp Curatorial Fellow

Top: Edwin A. Harleston (American, 1882 – 1931). Pierre Samuel du Pont, 1924. Oil on canvas, 45.375 x 39.375 inches. 1976.077. Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

i Edwin A. Harleston, Boston, MA., to Elsie F. Harleston, Charleston, SC, November 26, 1923. Quoted in Maurine Akua McDaniel, Edwin Augustus Harleston, Portrait Painter, 1882 – 1931, PhD. diss (Emory University, 1994), 156.

ii Madeline G. Allison, “Harleston! Who Is E.A. Harleston?,” Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life (January 1924), 21 – 22.

iii “Race Artist to Paint Portrait of Rich Donor,” Pittsburgh Courier (November 29, 1924): 2

iv McDaniel 196.

v Ibid 197.

vi Executive Committee DuPont Testimonial Association, Dover, Delaware, to Edwin A. Harleston, Charleston, SC, February 23, 1925. Typewritten letter, Mae Whitlock Gentry Papers, Emory University, Atlanta, GA.