The Delaware Art Museum has begun an in-depth technical study of a key selection of Simeon Solomon’s paintings from public and private collections worldwide. The results from this comprehensive research will contribute to the first U.S.-based exhibition on Simeon Solomon at the Delaware Art Museum in 2027.

In collaboration with the University of Delaware and Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, an investigation into Solomon’s materials and techniques is being completed by an interdisciplinary team of curators, art historians, conservators, and scientists. We are seeking to answer questions related to the provenance, conservation history, and preservation of Solomon’s paintings for the future. Art historical research, coupled with technical evidence, will help develop an understanding of how Solomon’s methods evolved within the framework of nineteenth-century British painting practice.

Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) is a key figure in British art. He defied Victorian conventions of gender, class, and religion to become one of the most avant-garde artists of the nineteenth-century. Working among prominent colleagues in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, Solomon was unique as the only Jewish artist in the group. Solomon frequently depicted narratives from the Torah and Prophets, as well as scenes of Jewish cultural and liturgical practices. By the mid-1860s, he was exploring same-sex desire in his art. Following arrests for homosexual crimes in the early 1870s, Solomon was rejected by the art establishment in which he had previously thrived. Due to Solomon’s circumstances and biography, his artistic output represents an experimental and innovative approach to Pre-Raphaelite art. Yet, he was—and remains—overshadowed by his better-known contemporaries.

Early research in support of the exhibition is already underway, including the analysis of The Mother of Moses (1860) and Toilette of a Roman Lady (1869) from the Delaware Art Museum’s collection. A fascinating research project on two paintings entitled Diana and Atalanta (c. 1866), in collaboration with the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC), was also arranged for the academic year of 2024-2025. These preliminary analyses have provided an insight into how Solomon’s practice was influenced by his contemporaries, as well as driven by his own technical skill and exploration of religion and sexuality.

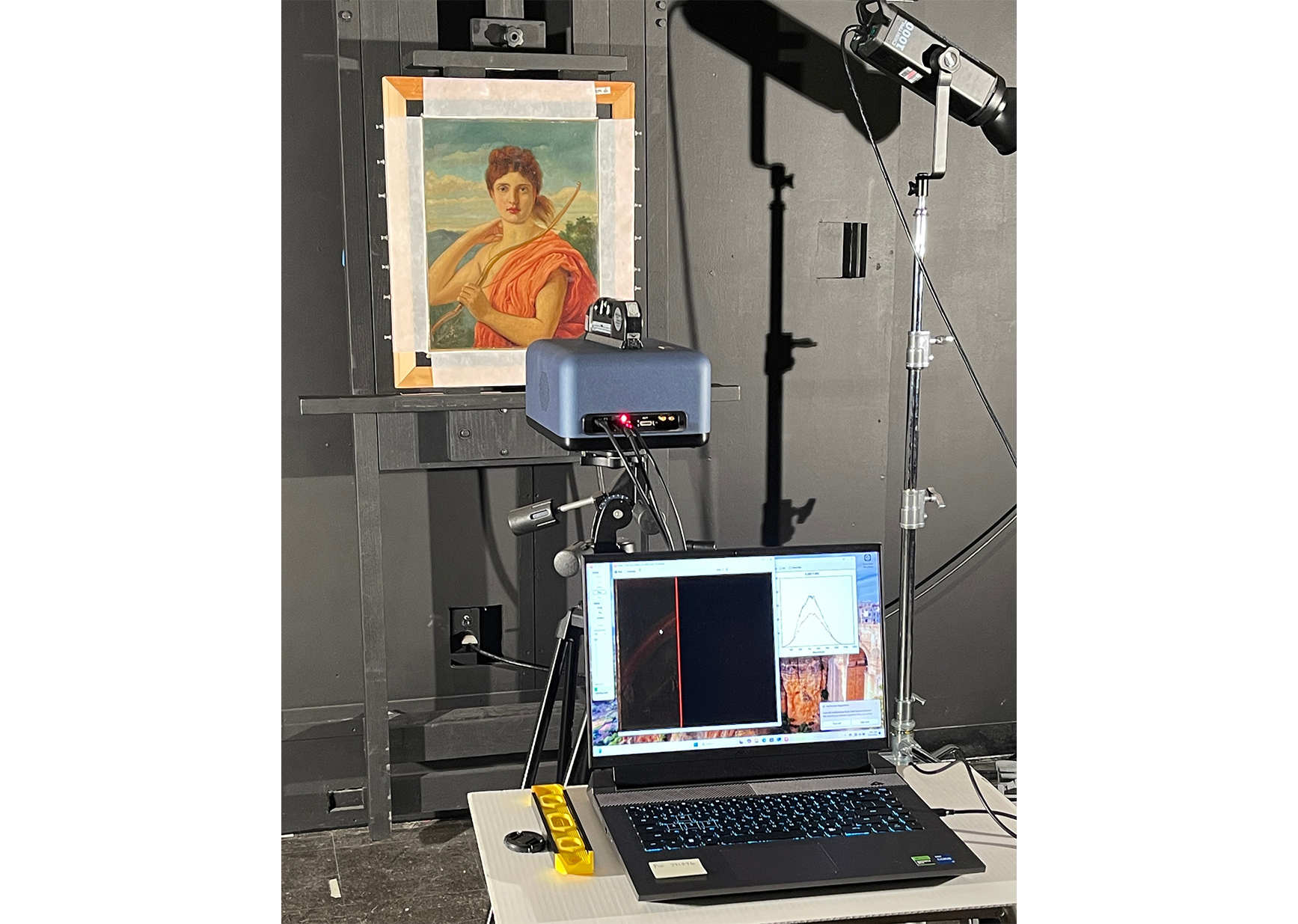

This exciting technical study emphasizes the use of non-invasive analytical techniques. Continue reading to discover some of the scientific methods that are being employed to reveal Solomon’s painting practice and artistic intentions.

Photography is undertaken using a digital camera to capture the painting’s condition before any treatment or analysis begins. A photograph may also be captured in raking light, which involves illuminating the painting using a light source that has been placed at an oblique angle to the painted surface. Examining paintings in raking light helps to examine the surface texture and topography, which allows for close study of Solomon’s technique and for documenting condition issues.

The exposure of paintings to ultraviolet light can help distinguish between varnish types and identify evidence of retouching or areas of previous damage, which is valuable in understanding a painting’s condition history. Ultraviolet light is also a helpful tool for identifying the presence of certain pigments. For instance, some red lake pigments exhibit a characteristic pinkish-orange fluorescence when illuminated under ultraviolet light.

Optical Microscopy plays a crucial role in this study by allowing the examination of brushstrokes, paint layers, pigments, and the overall condition of paintings under high magnification. Looking at paint cross-sections under the microscope is also a useful technique. This process involves taking a microscopic sample from the edges of a painting or from an area of existing loss/damage. The sample is embedded in resin and polished to reveal the layer structure of the painting. The paint cross-section is analyzed under a microscope to distinguish varnish layers, paint layers, types of pigments, and binding media. Key pieces of information can often be gleaned from the smallest areas.

Infrared Reflectography (IRR) involves the use of infrared radiation to penetrate through the paint layers to reveal carbon-based underdrawing and identify any changes made to the composition. In looking through the paint layers, we can uncover Solomon’s initial designs and understand how his artistic intentions may have changed during the painting process.

X-radiography can provide a tantalizing window into the original construction and condition of works executed on canvas, paper, or panel. Often, modifications and later alterations (completed by Solomon or a previous conservator) can be seen that are no longer visible to the naked eye as they remain hidden under layers of paint.

Portable X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS) help to develop an improved understanding of the pigments used by Solomon. XRF involves directing X-ray beams toward localized areas of the painting to determine the elemental composition of pigments. FORS uses a fiber optic probe and a light source to illuminate a small area of the artwork and collect reflected light from the painted surface. The data produced by both methods provide a holistic understanding of the material composition of the artist’s paints – therefore aiding in the dating of works and selection of appropriate conservation treatments.

Reflectance Imaging Spectroscopy (RIS) is a form of hyperspectral imaging that captures the unique spectral signature of materials in a painting by analyzing the light they reflect across a wide range of wavelengths. The captured light is broken down into thousands of narrow spectral bands, creating a continuous spectrum for each pixel in the image. As each material in a painting has a unique spectral fingerprint (how it reflects or absorbs light at different wavelengths), RIS can be used to identify and map specific pigments across a whole painting.

Meet the Team!

This collaborative technical study was initiated in 2023 by Dr. Sophie Lynford, Annette Woolard-Provine Curator of the Bancroft Pre-Raphaelite Collection, and Dr. Roxanne Radpour, Assistant Professor in the Departments of Art Conservation and Electrical and Computer Engineering at The University of Delaware. Dr. Radpour is a conservation scientist with a specialty in advanced chemical imaging and non-invasive analyses of cultural heritage materials and founded the Imaging Science Laboratory for Cultural Heritage (ISLα-CH) at UD.

Alexandra Earl is a Paintings Conservator and graduated from The Courtauld Institute of Art, London in 2024. Alexandra is currently the Pre-doctoral Conservation Fellow at the Delaware Art Museum and will begin her PhD on Simeon Solomon at The University of Delaware in the Preservation Studies Program in August 2025.

This research is being conducted with the support of the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory (SRAL), The Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) program, and ISLα-CH. We are especially grateful to the following individuals for their expertise and involvement in the project:

SRAL: Dr. Rosie Grayburn (Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library), Dr. Liora Mael (UD ARTC), and Catherine Matsen (Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library)

Conservators: Mina Porell (Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library) and Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner (UD ARTC)

Students: Taryn Nurse (Winterthur/UD Program in Art Conservation), Richard Breder (UD), Natalia Castilla (Universidad Nacional de Colombia)

Stay tuned for the results of our technical study in our 2027 exhibition and for more blogs in this new series, “Behind the Scenes in Conservation”!

Top: Alexandra Earl taking a closer look at The Mother of Moses (1860)