October 1, 2022 – February 5, 2023

To complement the major special exhibition, A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn & William De Morgan, the Delaware Art Museum has mounted the show, Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites, drawn primarily from the museum’s permanent collection. One of the significant contributions of A Marriage of Arts & Crafts is to foreground the work of two artists who have been understudied in the robust literature on the Pre-Raphaelite, Aesthetic, and Arts and Crafts movements. On view simultaneously, Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites brings together over forty works by similarly overlooked artists affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelite circle. By featuring these lesser-known artists, the show seeks to recover them from the margins of art history and position them at the center of the Pre-Raphaelite narrative.

The exhibition is comprised of four sections:

Partners & Daughters

Women artists were crucial to the Pre-Raphaelite movement and their work accounts for more than half of the objects on view. Several were the wives and daughters of better-known male counterparts. Artists represented include Winifred Sandys, Marie Spartali Stillman, Effie Stillman, Constance Phillott, Barbara Bodichon, and Alice Boyd.

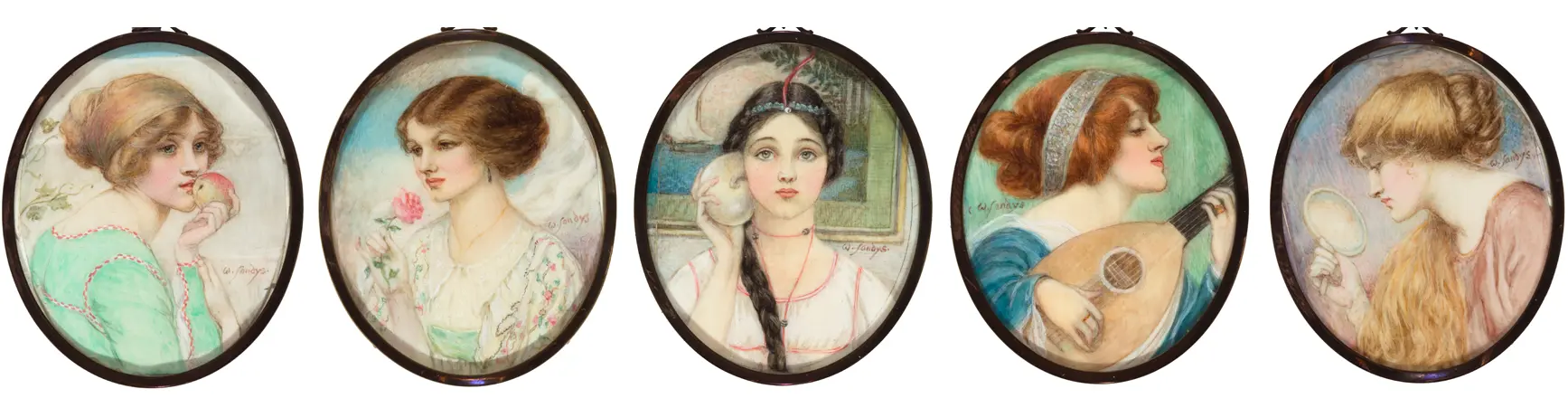

Left to Right: Taste; Smell; Hearing; Touch; Seeing, 1911-1912. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on ivory, 3 × 2 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Left to Right: Taste; Smell; Hearing; Touch; Seeing, 1911-1912. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on ivory, 3 × 2 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Winifred Sandys received artistic training from her father, Frederick Sandys, an artist closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. A group of her miniatures in the exhibition personify the five senses. Each woman engages with an object that stimulates a sensory response. Despite the modest dimensions, each scene is portrayed with intricate detail. Sandys pictures patterned textiles, delicate jewelry, and elaborate hairstyles.

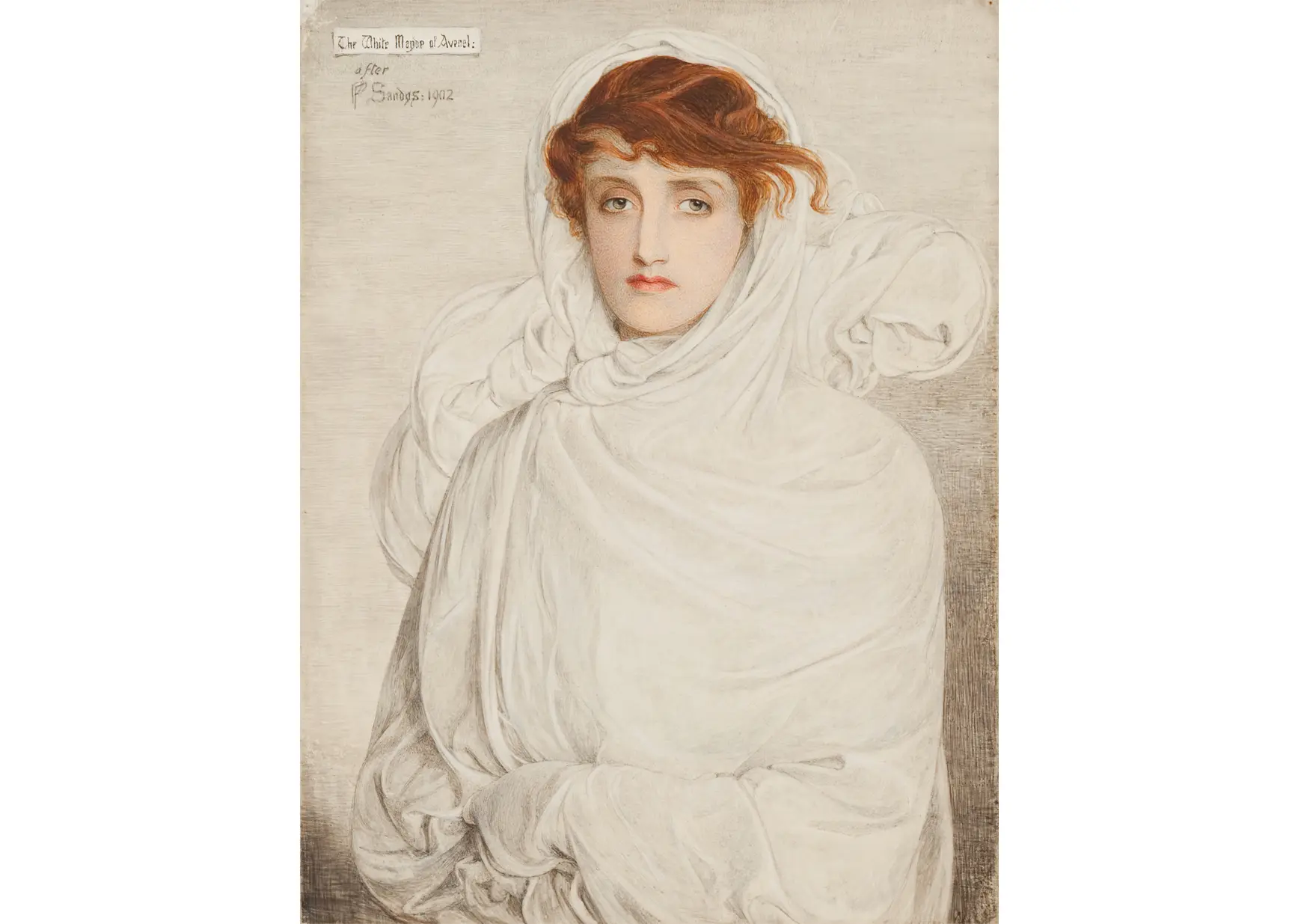

White Mayde of Avenel, after 1902. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on vellum, 8 × 6 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

White Mayde of Avenel, after 1902. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on vellum, 8 × 6 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Following her father’s death, Winifred sought to support her family in creative ways. In addition to selling her own work, she also made copies of her father’s. White Mayde of Avenel is a miniature replica of her father’s drawing of the same title. It illustrates a supernatural character from Sir Walter Scott’s novel, The Monastery (1820). The figure’s windswept hair and scarf, paired with her white garment, add to her ghostly appearance.

Followers & Assistants

Left: Apple Stem, 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, watercolor and gouache on buff paper, 9 × 7 1/2 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Right: Apple Blossom, c. 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, ink, watercolor, and gouache on buff paper, 9 9/16 x 7 11/16 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Left: Apple Stem, 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, watercolor and gouache on buff paper, 9 × 7 1/2 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Right: Apple Blossom, c. 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, ink, watercolor, and gouache on buff paper, 9 9/16 x 7 11/16 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Many lesser-known artists in the Pre-Raphaelite circle served as assistants to their more famous peers. Objects in this section include work by Joseph Swain, Frederic Shields, Thomas Rooke, and George James Howard. Shields, for instance, supported Dante Gabriel Rossetti in return for studio use. He created closely observed drawings of apple blossoms as a visual aid for Rossetti’s A Vision of Fiammetta. Faithful to the key features of the apple blossom, Shields included the blossoms’ hallmark pale pink petals, elliptical leaves, and yellow-tinged stamens.

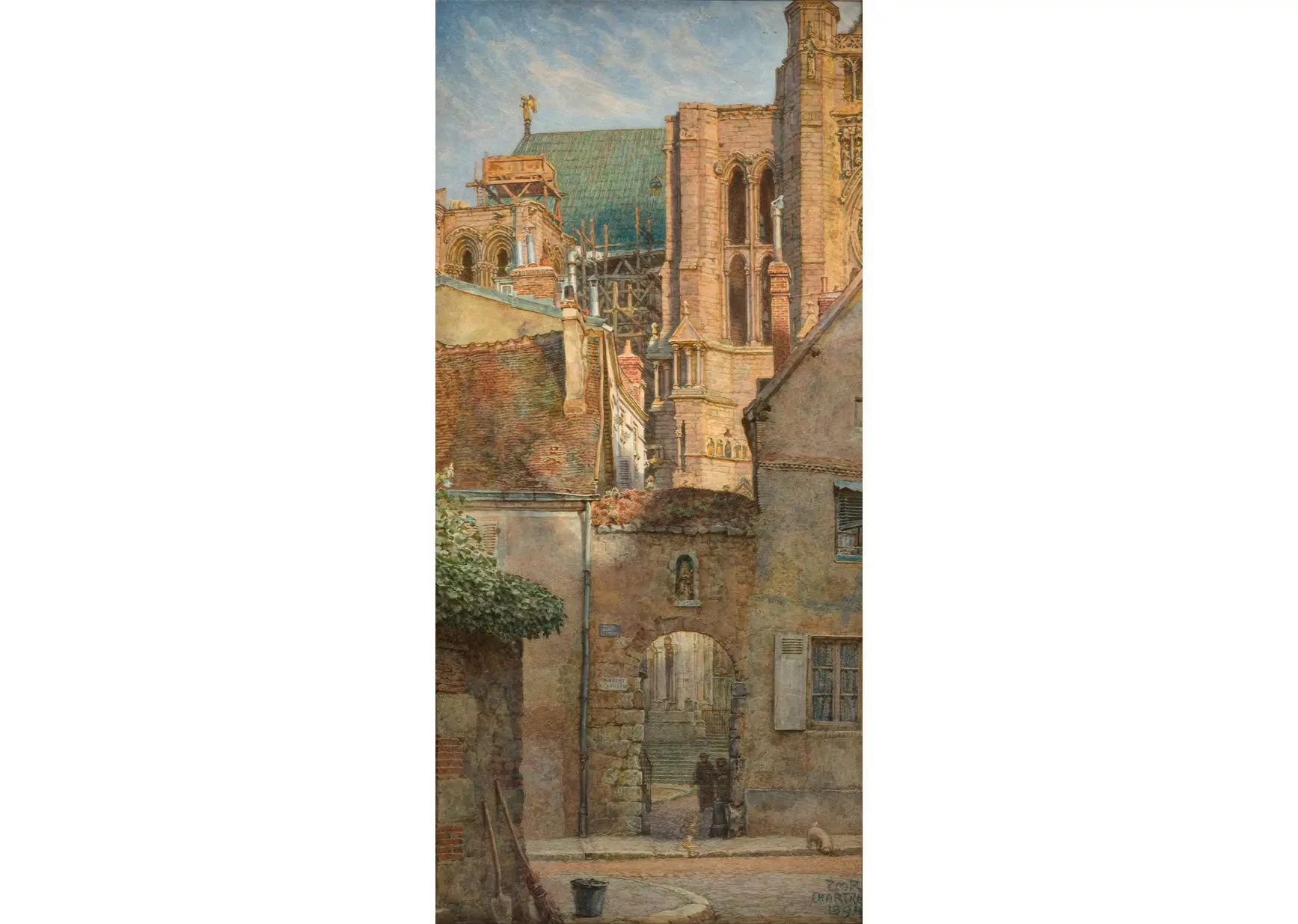

A Gate leading to the North Transept of Chartres Cathedral, France, 1894. Thomas Matthews Rooke (1842–1942). Watercolor over graphite, 19 1/4 × 9 ¼ in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

A Gate leading to the North Transept of Chartres Cathedral, France, 1894. Thomas Matthews Rooke (1842–1942). Watercolor over graphite, 19 1/4 × 9 ¼ in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Rooke similarly aided Edward Burne-Jones, painting flowers into one of his massive canvases, Sleep of King Arthur in Avalon. He was also commissioned by John Ruskin to travel across Europe depicting sites that might soon be demolished. Rooke visited Switzerland, Italy, and France, executing meticulous watercolors of cottages, churches, and Alpine scenery. Chartes and its cathedral were among Rooke’s favored subjects. His watercolors register what contemporary cameras could not, particularly the subtle chromatics of aged stone. Beneath the arch of the stone gate are figures represented with nearly transparent wash. They serve as a reminder that much of the surrounding architecture is near vanishing.

Such proximity to celebrated painters had tangible benefits for amateur and aspiring artists. They accessed materials, studio space, and instruction from prominent colleagues. But their contributions to acclaimed works were often uncredited.

The American Pre-Raphaelites

Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites is one of few exhibitions to place British Pre-Raphaelite works alongside those of the lesser-known American Pre-Raphaelites. The American movement began roughly a decade later than the founding of the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The American Pre-Raphaelites were a uniquely interdisciplinary group composed of politically radical abolitionist artists and like-minded architects, critics, and scientists. Active during the Civil War, they united in a spirit of protest, seeking sweeping reforms of national art and culture.

Anemones, 1884. Henry Roderick Newman (1843–1917). Watercolor on paper, 9 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. Paul Worman Fine Art, Worcester, MA.

Anemones, 1884. Henry Roderick Newman (1843–1917). Watercolor on paper, 9 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. Paul Worman Fine Art, Worcester, MA.

The exhibition features watercolors, intricate graphite drawings, and etchings by Thomas Charles Farrer, Henry Farrer, John Henry Hill, Henry Roderick Newman, and William Trost Richards. They applied Pre-Raphaelite techniques to their paintings and drawings of American landscapes. Like their British counterparts, the American Pre-Raphaelites captured natural elements with precise detail. But they rejected the medieval, biblical, and literary narratives of the British movement. Instead, they produced landscapes, nature studies, and still lifes of modest dimensions.

Barbara Bodichon’s Landscapes

Ventnor, Isle of Wight, 1856. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891). Watercolor and gouache on paper [with scratching out], 28 × 42 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2016.

Ventnor, Isle of Wight, 1856. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891). Watercolor and gouache on paper [with scratching out], 28 × 42 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2016.

The Delaware Art Museum holds a number of works by Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, an artist and activist for women’s rights, and a group of her landscapes represent one section of the exhibition. Bodichon gained financial independence at age 21 and she subsequently toured Europe widely. Breaking with social conventions, she often traveled without a chaperone and with female friends, including the writer George Eliot. Bodichon’s thirst for freedom also extended to her painting practice. She enjoyed working out of doors, often in difficult-to-reach locations. Rossetti described her as “a young lady . . . who thinks nothing of climbing a mountain in breeches, or wading through a stream in none.” [1]

Many of the works by Bodichon on view in the exhibition are sketches she completed while traveling. Her large watercolor, Ventnor, Isle of Wight, is the centerpiece of the installation. The artist’s vibrant palette and intricate depiction of flora and rocks were Pre-Raphaelite hallmarks. When Bodichon exhibited the picture at the Royal Academy in 1856, Dante’s brother William Michael Rossetti described it as a “capital coast scene . . . full of real pre-Raphaelitism.” [2]

Between A Marriage of Arts & Crafts and Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites, visitors to the Delaware Art Museum this fall will be introduced to numerous artists associated with Pre-Raphaelitism, each of whom are deserving of significant scholarly and popular attention.

Sophie Lynford

Annette Woolard-Provine Curator of the Bancroft Pre-Raphaelite Collection

[1] Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Christina Rossetti, November 8, 1853. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, eds. Oswald Doughty and John Robert Wahl, vol. I (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 163.

[2] William Michael Rossetti, “Art News from England,” The Crayon, August 1856, p. 245.

Top image: Coastal landscape by moonlight, not dated. Alice Boyd (1825–1897). Watercolor over graphite with scratching out, with gouache and lead white, 10 1/16 × 13 15/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2022.