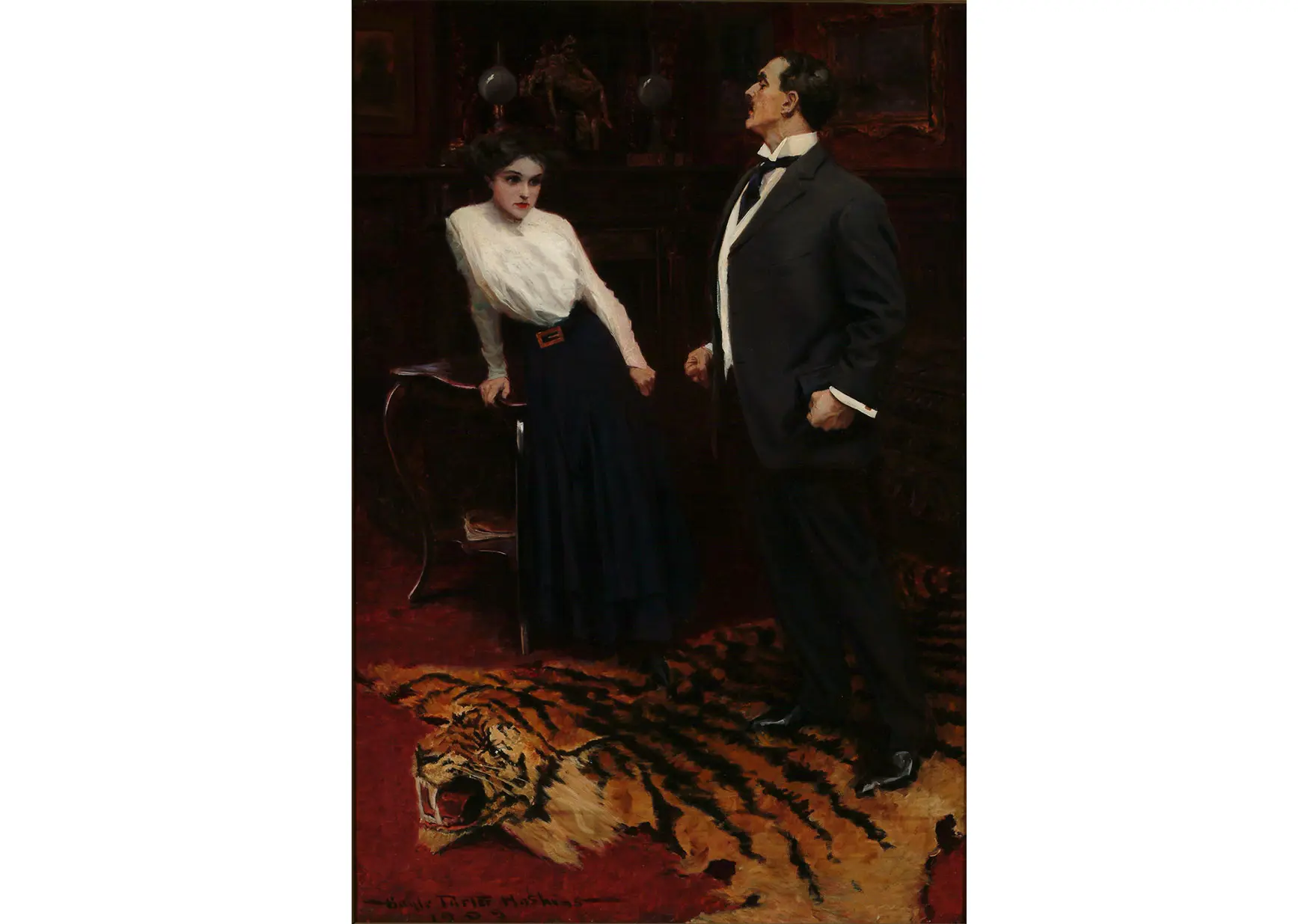

A few years ago, Mary Holahan, Curator of Illustration Art, drew attention to this painting with a timely and well-researched blog post. She elucidated the moment Hoskins depicted, when the “19-year-old stenographer shrinks from her sinister boss’s demand that she succumb to his advances.” Her post describes the plot and reception of Dejeans’ novel about sexual abuse in the workplace. And the gallery label Mary wrote for the work highlighted the tiger-skin rug with the animal’s bared fangs, which echoes the character of the brutish, predatory employer.

When we began testing ideas with focus groups for the reinstallation of the illustration collection, this painting and Mary’s analysis of it engaged our visitors, who linked it to the #metoo movement. They wanted to know even more, asking in particular about the statuette on the mantelpiece behind the young woman. Taking over responsibility for the illustration collection after Mary’s retirement, I wanted to know more, too, so I started looking closely.

Facing each other at last, the girl white, shaking, her eyes aflame (detail), 1909.

Facing each other at last, the girl white, shaking, her eyes aflame (detail), 1909.

The painting is dark and the details of the statuette are difficult to make out, but it’s carefully delineated and beautifully composed. I thought it likely that the painted sculpture was a miniature version of a real sculpture. Like the rug, I hoped it would add to the illustration’s power.

Like many works of art that will be featured in the reinstalled galleries, this Hoskins painting was slotted for conservation. When it went to our conservator, Mark Bockrath, I asked him to let me know if he could see more as he examined and cleaned it under bright light. In a series of emails this summer, we exchanged photographs of the painting and scans of the published version and talked about what that statuette might depict. With one figure held and draped across another, at first glance (from an art history major) the sculpture looks like a Pietà or lamentation of Jesus, but that doesn’t add anything to the story. I thought it might be the abduction of Persephone by Hades, but I couldn’t find an example of that mythological theme resembling this composition.

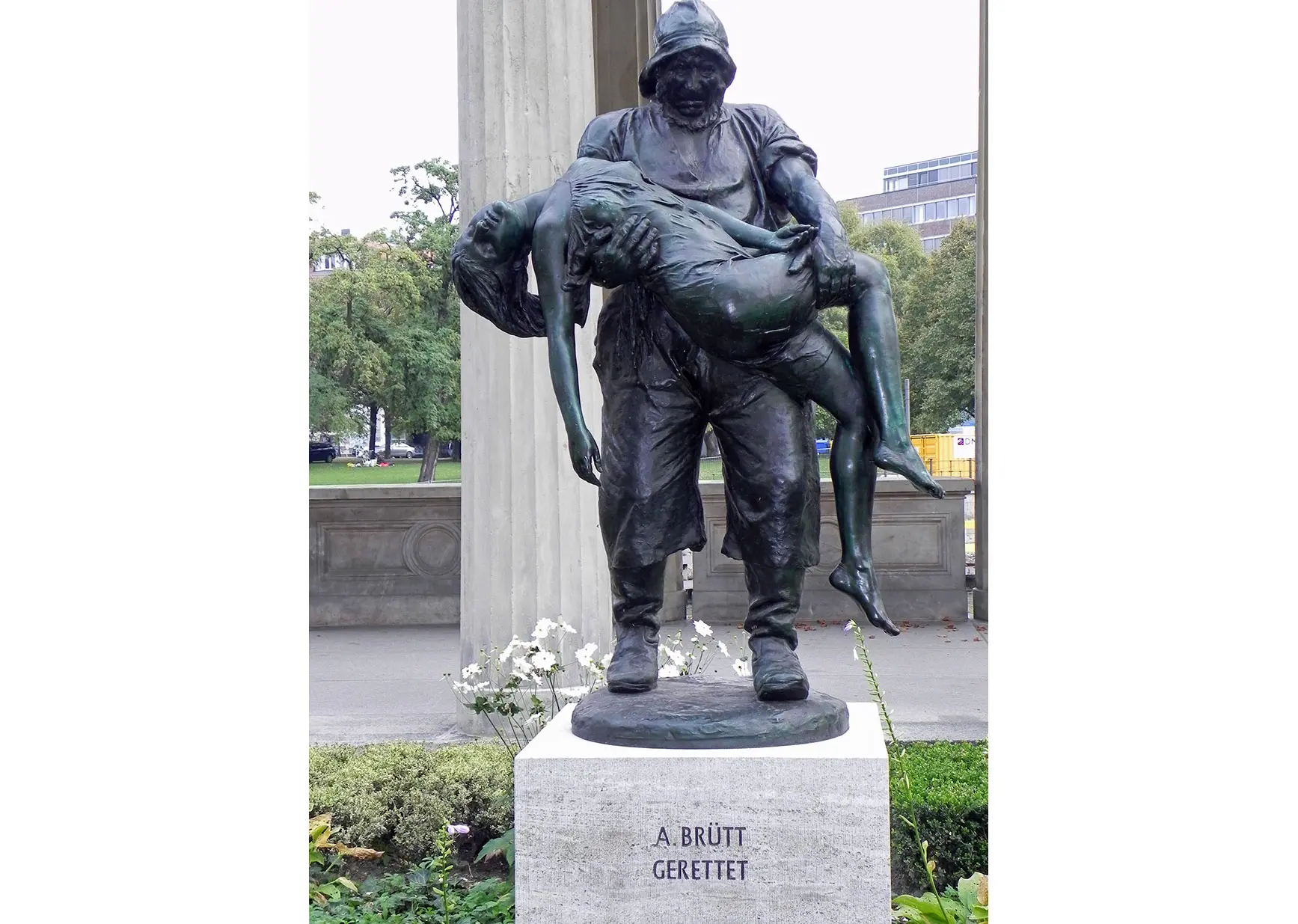

And what about that hat on the standing figure? I mused on conquistadors’ helmets, and Mark half-joked that his attire looked more like a fisherman’s gear. After that, I saw echoes of Winslow’s Homer’s heroic lifesaving scenes. So, I started a Google image search using words like fisherman, sculpture, saved, and drowning. Then, I found it really fast. The statuette seems to be a small version of Saved, an 1887 sculpture by Adolf Brütt. The modern, heroic subject, which the artist claimed to have witnessed, resonates thematically with Winslow Homer’s 1884 masterpiece The Life Line, as does and the combination of strong man and supine, drenched woman.

Saved, 1887. Adolf Brütt.

Saved, 1887. Adolf Brütt.

A large bronze cast of Saved (familiarly called The Fisherman)—Gerettet (Der Fischer) in German—stands outside the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin today. It was famous in its day, winning Brütt a prize and being selected for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Living in Chicago in 1904, the 17-year-old Hoskins might have traveled to the world’s fair in St. Louis—over 19 million people did—but there was a lot to see there. Hoskins probably encountered a tabletop version similar to the one he placed on the mantel. Like many popular sculptures, Saved was reproduced at a domestic scale. A 17-inch version sold at auction for €2,000 in 2018, and vintage postcards featuring the sculpture still can be bought online.

Now that we have identified Saved, how might it help us understand the painting? I think the bronze, which is displayed in the predatory boss’s office, speaks to that character’s understanding of himself. The author of the novel makes it clear that the man thinks that what he’s doing helps the young woman. He sees himself as a savior, lifting her and her family out of poverty.

Hoskins’ choice of sculpture is pointed, though more subtle than the tiger-skin rug. Neither is mentioned in the story, and I don’t think these are purely decorative choices. The inclusion of the Brütt is more like an art-historical Easter egg—something that adds to the story for the viewers that recognize it. I imagine more viewers recognized Saved in 1909, and I hope they appreciated Hoskins’ evocative details as much as I do now!

Heather Campbell Coyle

Chief Curator and Curator of American Art

Top image: Facing each other at last, the girl white, shaking, her eyes aflame, 1909. Cover and frontispiece for The Winning Chance by Elizabeth Dejeans (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1909). Gayle Porter Hoskins (1887–1962). Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquired by exchange, 1971.