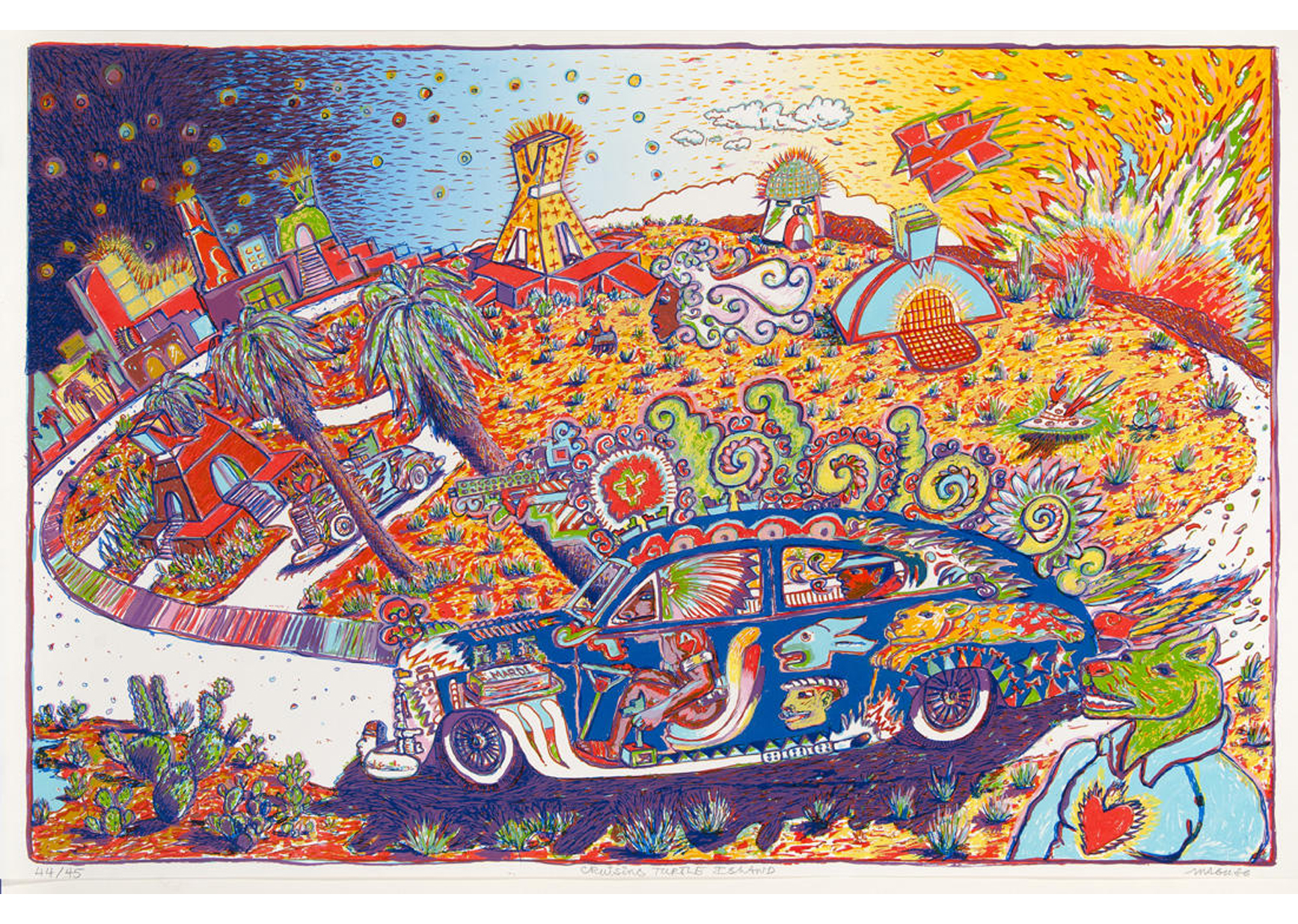

In Gilbert Magu Luján’s print Cruising Turtle Island, the road doesn’t disappear into the sunset. It stretches around the horizon, dipping just out of sight before reappearing to convey a colorful low-rider car along a surface of white sand. A fiery heart rises – or is it setting? – in place of the sun. Opposite, a city lights up an indigo night sky. Buildings in the shape of an “L” and an “A,” alongside cactuses and palm trees, help us get our bearings. As our eyes follow the car and its passengers, we find ourselves in a radically re-imagined Los Angeles where Luján pictures Chicano identity mapped onto the land.

Gilbert Luján, nicknamed Magu, grew up in East Los Angeles during the 1940s and 1950s, a time before his neighborhood’s streets were paved. He lived with his maternal grandparents, Eladio and Luciana Sanchez, who had emigrated from Mexico in 1926.1 After receiving an MFA in ceramics in 1973 from the University of California – Irvine, Luján moved home to East LA, where he became a founding member of Los Four, a group of artists intent on defining and advocating for a distinctive Chicano aesthetic. For most of his career, he worked primarily in sculpture, painting, and printmaking. Alongside other artists in Estampas de la Raza, he pieces together and narrates identities complicated by the US-Mexico border.

Luján uses utopian landscapes like this one to image a present rooted in Chicano and Indigenous realities rather than settler-colonial boundaries. Scholar Karen M. Davalos has written that his imaginary landscapes constitute a form of “emplacement.” According to Davalos, emplacement can be a process of healing: “The wounds emplacement addresses include those of injustice, erasure, and alienation—in other words, the injuries of nationalism and colonialism that continue to define the social order.”2 But I say image rather than imagine because, crucially, Luján represents a real cultural landscape even if it does not match Western conventions of representational space and time. Luján visualizes an alternate reality with such forcefulness and consistency that it becomes, in his work, real.3 As a leader within the LA Chicano movement, Luján was concerned with the protection and flourishing of Chicano identity and self-determination. As part of that movement, he helped give voice to new bodies of theory, stories, and ways of telling history.

Many of Luján’s prints combine the mythical Chicano homeland of Aztlán with his own self-made utopia, Magulandia. Aztlán was the northern mythical homeland of the Aztec and Mexica. During the 1960s and 1970s, it became an important symbol of cultural identity and unity for people of Spanish and Indigenous descent in the Chicano movement. Magulandia was a self-invented utopia that was part of Luján’s broader project of building a Chicano aesthetic and articulating Chicano identity.4 In this print, Luján positions these landscapes as part of “Turtle Island,” an Indigenous term for North America that originated with the Haudenosaunee’s creation stories but has become widely used in pan-Indigenous circles. By identifying Aztlán and Magulandia with Turtle Island, Luján aligns his work within the Chicano movement with pan-Indigenous assertions of sovereignty and self-determination across the United States.

The car carries two figures along the sweeping path. The driver’s body is visible through the car, almost as though it is a part of the body of the car. The figure wears sandals and a feather headdress that suggest he is an antepasado, or Aztec ancestor.5 The front fender has an Olmec head decoration while the body contains animals who seem almost to drive the vehicle forward. The passenger in the backseat wears a fedora, his body hidden by the car. Unlike the antepasado in the front, he is almost entirely hidden from view. Yet the two figures are in dialogue with one another, which Luján makes clear through the Nahuatl speech glyphs drifting out of the mouth of each. Nahuatl was the language of the Mexica and other Aztec nations. Spanish missionaries recorded Nahuatl speech glyphs in sixteenth century codices that had just received broader scholarly attention in the 1970s, a decade before Luján made this print. The swirls and curls of color around the car have a similar shape. Luján uses these glyphs to put the past and present into conversation with one another, showing that Nahuatl history and aesthetics are just as much a part of the present as they are of the past. Luján called cars, and especially lowriders, “cultural vehicles.”6 Surrounding and threading through the car—a symbol of modernity—these symbols establish an Indigenous present.

Luján uses the landscape to show that Chicano identity does not simply refer to immigrants who cross the settler border between Mexico and the United States. Chicano also includes the Indigenous people who are not defined by national borders and who maintain a relationship with their homelands and culture even as they travel, or cruise, across North America. Pyramids rise from the desert, illuminated with electric lights. Their blocky, geometric shapes reference Aztec architecture, but dogs’ legs form their bases as dogs’ heads howl to the sky at the peak. To the left, one of the pyramids is set up as a single-family home, another low-rider settled in the driveway next to it. Luján often uses dogs as a metaphor for mixed Indigenous-Mexican heritage. Karen Davalos has described these buildings as “contemporary technological developments.” They are not “neoindigenous” or “appropriations of an Indigenous past,” but proof of how hybrid forms of modernity are built upon Indigeneity.7 Western notions of forward progress usually define history as a forward driving line. Many Indigenous intellectual traditions see time as a circle. In Cruising Turtle Island, night and day hang simultaneously in the same saturated sky.

Luján made this print at Self Help Graphics, a community-based print shop run out of East LA. Like Los Four, Self Help and other print shops represented in Estampas de la Raza were integral to the development of a Chicano aesthetic and art market. Without these institutions and collectors like Harriet and Ricardo Romo, whose collection is on display, Chicano artists were largely cut off from the fine art world. Not only did artists need to build their own aesthetic; they also needed to generate their own market and values. In a founding document for Los Four, Luján writes that alienation is the fundamental experience of urban socialization.8 He worked through collaborations and workshops to make the Chicano art movement one of anti-alienation and community formation governed by values of love, acceptance, and celebration.

In Luján’s print, neither Aztlán nor Turtle Island are static places defined by the fixed lines and points that nation-states have used to impose themselves onto these landscapes. Instead, the inhabitants are modern people who inhabit their world and build new technology in fluid dialogue with their antepasados. Colonialism changed, but did not a rupture, their connections to the past. The burning heart blazing across the sky, on the chest of the anthropomorphic dog in the bottom right corner, and on the engine of the car parked in its driveway turns the landscape of Turtle Island into a place of belonging, powered by the revelatory light of acceptance.

Julia Hamer-Light

PhD Candidate, Depart of Art History

University of Delaware

Image: Gilbert “Magu” Luján, Cruising Turtle Island, 1986, screenprint on paper, image: 24 1⁄4 × 36 1⁄2 in. (61.6 × 92.7 cm) sheet: 25 × 38 1⁄4 in. (63.5 × 97.2 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Frank K. Ribelin Endowment, 2020.22.1.

1 Gilbert “Magu” Luján, interview with Karen Mary Davalos, September 17, 19, and 22, and October 1 and 8, 2007, Ontario, California. CSRC Oral Histories Series, no. 4. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2013.

2 Karen Mary Davalos, “The Landscapes of Gilbert ‘Magu’ Luján: Imagining Emplacement in the Hemisphere,” in Aztlán to Magulandia: The Journey of Chicano Artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján, ed. Constance Cortez and Hal Glicksman (Munich: University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine in association with DelMonico Books Prestel, 2017), 37.

3 Hal Glicksman, “Introduction,” in Aztlán to Magulandia: The Journey of Chicano Artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján, ed. Constance Cortez and Hal Glicksman (Munich: University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine in association with DelMonico Books Prestel, 2017), 17.

4 Glicksman, 17.

5 University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine, “Aztlán to Magulandia: The Journey of Chicano Artist Gilbert ‘Magu’ Luján,” Google Arts & Culture, accessed May 5, 2023, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/aztlán-to-magulandia-the-journey-of-chicano-artist-gilbert-magu-luján/ZwWRt0v2OfvRJw.

6 Maxine Borowsky Junge, “Gilbert ‘Magu’ Luján–The Social Artist,” in Aztlán to Magulandia: The Journey of Chicano Artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján, ed. Constance Cortez and Hal Glicksman (Munich: University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine in association with DelMonico Books Prestel, 2017), 84.

7 University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine, “Place and Placement: Symbolic Geographies in the Work of Gilbert ‘Magu’ Luján,” Google Arts & Culture, accessed May 5, 2023, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/place-and-placement-symbolic-geographies-in-the-work-of-gilbert-“magu”-luján/6QXBJBBLJhwCLw.

8 Constance Cortez and Hal Glicksman, eds., Aztlán to Magulandia: The Journey of Chicano Artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján: (Munich: University Art Galleries, University of California, Irvine in association with DelMonico Books Prestel, 2017), 119.