In January of this year the Museum was fortunate to acquire a stained-glass window designed by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co. The window, featuring the Old Testament patriarch Noah, was offered through a dealer, one of several windows featuring patriarchs and saints, originally installed in the Chapel of Cheadle Royal Hospital, near Manchester.

Between 1906 and 1915 Morris & Co was engaged in creating the windows for the newly built Chapel of the Cheadle Hospital. Stained glass windows made up a significant portion of the products sold by the decorative arts firm from its beginnings in 1861 as Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co, a collective which included Burne-Jones, among other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. The early years of the Firm coincided with the Gothic Revival and the subsequent boom in church building and refurbishment. The level of excellence which came to be associated with the Firm’s glass was crucial in establishing its financial success.

Morris and Burne-Jones’s interest in stained glass derived from a shared passion for the medieval period developed while the two were at Oxford University in the early 1850s. Their joint enthusiasm developed into a unique creative partnership in which Burne-Jones’s linear designs were augmented by Morris’s sense for color. Morris wrote, “Any artist who has no liking for bright colour had better hold his hand from stained glass designing.”[1] And Burne-Jones commented, “figures must be simply read at a great distance…the leads are part of the beauty of the work…”[2]

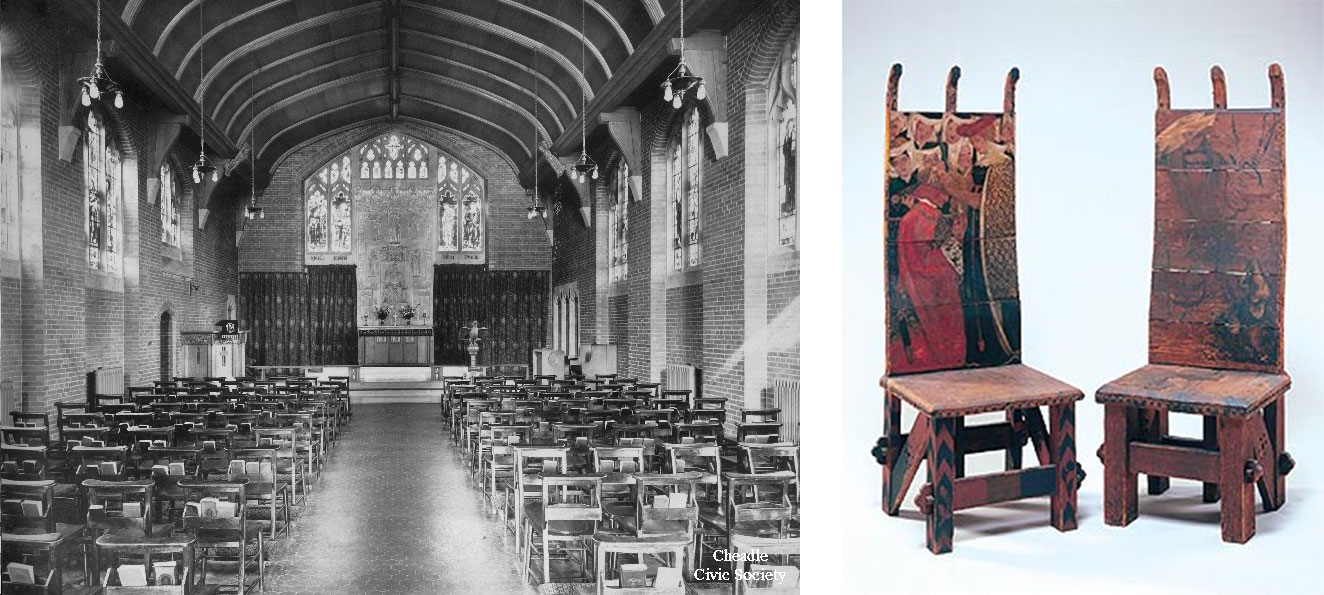

Above, left to right: Cheadle Royal Hospital Chapel, c. 1920. Cheadle Civic Society Archives. | The Arming of a Knight and Glorious Gwendolen’s Golden Hair, 1856-1857. William Morris (1834-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Painted deal, leather, and nails, Delaware Art Museum, Acquired through the Bequest of Doris Wright Anderson and through the F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 1997.

Above, left to right: Cheadle Royal Hospital Chapel, c. 1920. Cheadle Civic Society Archives. | The Arming of a Knight and Glorious Gwendolen’s Golden Hair, 1856-1857. William Morris (1834-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Painted deal, leather, and nails, Delaware Art Museum, Acquired through the Bequest of Doris Wright Anderson and through the F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 1997.

With the exception of Miriam (1896),[3] all the designs were drawn within a two-year period, 1874-76. Their style reflects the artist’s assimilation of Italian Renaissance art developed on several visits to Italy and culminating in an 1871 viewing of the Sistine Chapel. His wife Georgiana recalled, he “…bought the best opera-glass he could find, folded his railway rug thickly, and, lying down on his back, read the ceiling from beginning to end, peering into every corner and reveling it its execution.”[4] His work from this point forward reflects the influence of Michelangelo and the artists of the High Renaissance.

It is estimated that Burne-Jones created over 750 stained glass designs in his lifetime, the number all the more astounding if consideration is given to the many other media in which he was simultaneously working. His style was uniquely suited to stained glass work. He understood its strengths and weaknesses, writing, “…It is a very limited art and its limitations are its strength, and compel simplicity — but one needs to forget that there are such things as pictures in considering a coloured window—whose excellence is more of architecture, to which it must be faithfully subservient.”[5] His understanding of the media enabled him to exploit to capacity the potential of the lead work, giving a level of expression and character rarely achieved to the flattened surfaces of the glass.

The commission for the Cheadle Chapel came well after the death of both Morris and Burne-Jones, however, the Firm’s huge stock of stained-glass cartoons continued to be re-used in new commissions. Window designs were recorded and photographed so that prospective buyers could choose from a selection of images for their particular building. The window program at Cheadle was directed by John Henry Dearle, who served as Art Director for the Firm after Morris’s death in 1896. When the Chapel closed in 2001, the stained glass was removed and sold. Several of the windows are now in Museum collections including St Paul (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne and six in the Stockport Story Museum.

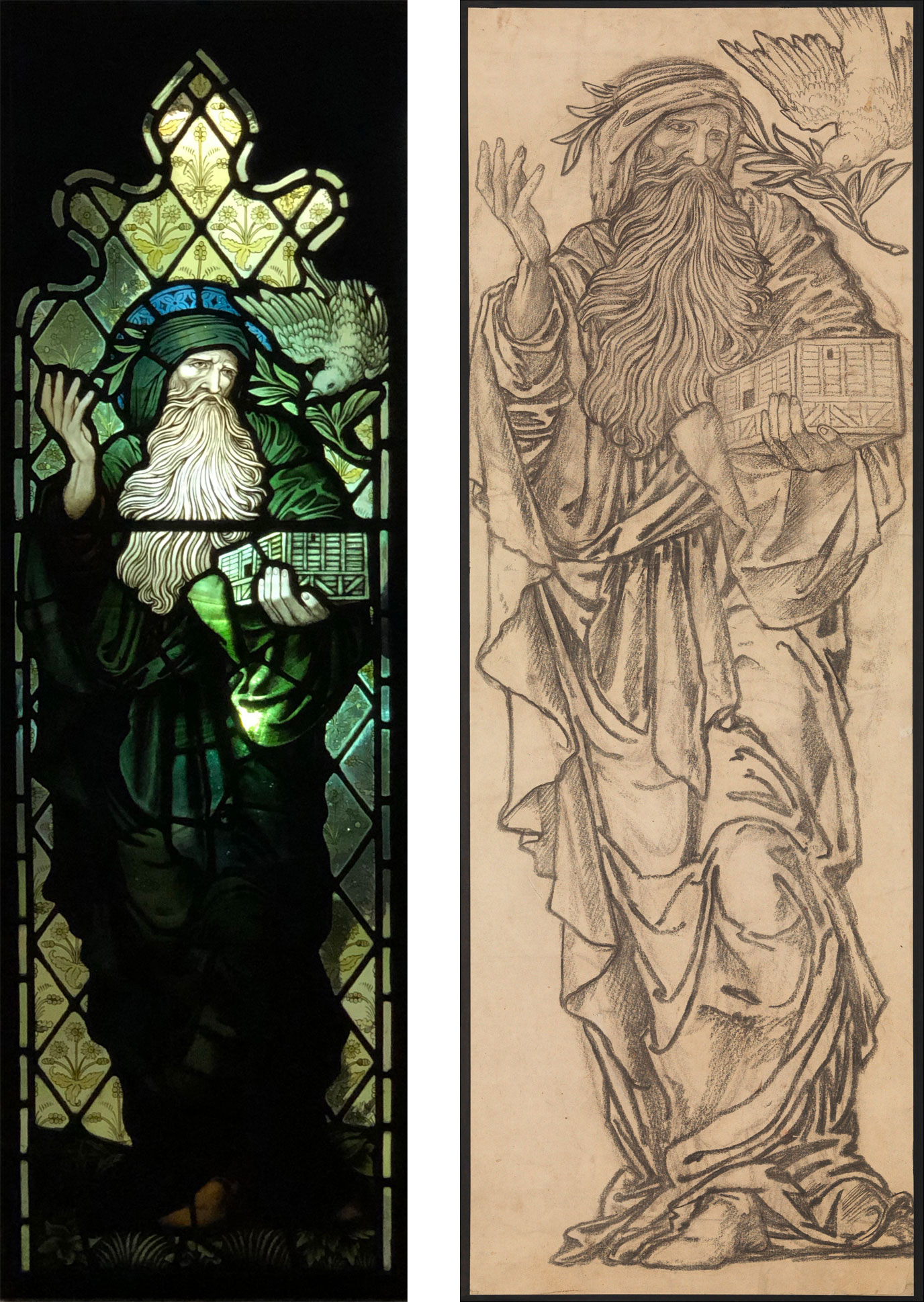

Enoch and Noah, the earliest of the designs under discussion, were located in the south side of the Cheadle Chapel,[6] as were Daniel, Jeremiah in a stunning gold-hued robe, Isaiah, and Miriam. Attributes cue the viewer in the identification of each. For instance, the Delaware Art Museum’s recently acquired Noah, with a gloriously abundant and patriarchal beard, holds the ark in his left hand while the dove bearing the olive branch appears at upper right. Miriam, clothed in a cloak of red, holds a timbrel which she played and sang after the parting of the sea. St John, St. Elizabeth, and St. Mark were located across the Chapel on the north side of the building. St Elizabeth, wearing a multi-hued green gown over a patterned white tunic bows her head in modesty and reticence. Burne-Jones’s subtle manipulation of line conveys her character of gentleness and humility.

A drawing for this window design is included in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The drawing would have been given to the glass painters in the Morris & Co. workshop to be translated to the stained-glass medium. The design would have been enlarged to the size of the window and used as a template for cutting the individual glass pieces. In some cases, Burne-Jones would include notes on the drawing to aid the craftsman in their work, although there are none on this sheet.

Burne-Jones kept an extensive record of his work for Morris & Co. in a series of account books, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. In addition to providing valuable information on date and cost, these books include a running commentary of humorous badinage, largely directed at Morris. Comments include lamentations over the poor remuneration received for work and apologetic criticisms for the quality of the work completed. In his typically self-deprecating manner, Burne-Jones described his designs for Isaiah and Jeremiah as two of “four major prophets on a minor scale designed I regret to say with the minimum of ability.”

This stunning group of windows is representative of the quality stained glass work produced by Morris & Co. a result of the deep friendship and collaborative creative partnership of Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris.

The Museum’s Noah will be featured in the reinstallation of the Museum’s Pre-Raphaelite galleries, part of a larger project to reinterpret all of the ground floor galleries. Noah will be presented adjacent to the two chairs, jointly created by William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti created for living quarters at Red Lion Square in London in 1855-6. This grouping of works will illustrate the importance of mediaeval art in the early Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, as well as in the development of Morris’s arts and crafts practice.

Top, left to right: Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) for Morris & Company, Noah, 1909. Stained glass, 60 x 19 2/3 (with wooden frame). Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2020. | Noah, 1874. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). Charcoal on paper, 45 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1948, (48.52).

[1] Chambers Encyclopedia, 1890.

[2] [Cited in Haslam and Whiteway (2008): 3]

[3] Miriam was taken from a figure of Deborah drawn in 1896 for the Albion Congregational Church, Ashton-under-Lyne.

[4] Memorials II: 26.

[5] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials, II:109.

[6] Enoch and Noah can be seen in situ today at Jesus College Chapel, Cambridge, part of a program which predated Cheadle.