Sometimes, despite the best efforts of art historians and even with the help of 21st-century technology and archival resources, as much as we dislike admitting it, there are questions that just can’t be answered definitively. The study of the work of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal (1829-1862), Pre-Raphaelite model, muse, artist, and poet, poses more unanswered questions than most, and that applies specifically to the drawing (one of three works by the artist in the Museum’s collection) under review here.

Best known as the face of avant-garde feminine beauty in the work of many of the early Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood paintings, Siddal’s own work has suffered the fate of many female artists of the past, having been cast aside as less important than those of her more successful male peers. In Siddal’s case, her artistic reputation was further expunged as she died at an early age, leaving little time for her mature style to develop. She died at age 33 of an overdose of the opiate, laudanum, potentially suffering from post-partum depression after the birth of a still-born child). She was daughter of a working-class cutler from Sheffield, employed as a dressmaker when she was first introduced to members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. While her family was not poor, economic survival would have precluded advancement of artistic endeavors, just as her female gender would have limited opportunities for training.

Siddal first became acquainted with members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood through their friend, the artist, Walter Deverell. The initial connection was probably through dressmaking engagements for the women of Deverell’s family. According to art historian Jan Marsh, Siddal somewhat boldly took advantage of the family’s artistic connections and showed examples of her own work to Deverell’s father, who was a principal of the Government School of Design. The important part of this particular biographical detail is that it shows Siddal’s had artistic intentions and acted on them prior to her relationship with the Pre-Raphaelite artists.

We do know that in 1849 she modeled for the character of Viola in Walter Deverell’s painting of Twelfth Night Act II, Scene IV (1850, oil on canvas, Private Collection). She continued to model for several artists of the group, most notoriously, as Ophelia in John Everett Millais’s famous painting (1851-2; oil on canvas, Tate Britain, London) of a scene from Hamlet. Around 1852 Siddal met Dante Gabriel Rossetti and shortly thereafter began modeling for him as well. Within the year she became his pupil and left off modeling to focus on her own work.

The details of her life including modeling and her on-again/off-again relationship with Rossetti are relatively well known, however, her creative output as artist and poet is less so. As Jan Marsh clarified in the recent exhibition and catalogue, Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood (National Portrait Gallery, London 2019), Siddal’s professional artistic aspirations appear to have been well in place prior to any association with the Brotherhood members and she may have viewed modeling as a way of breaking into the patriarchy of the artistic profession. This suggests a powerful and driving ambition given the hurdles of her working-class status and gender.

Rossetti’s training included the sharing of his enthusiasm for the work of William Blake and medieval manuscripts, as well as his dislike of current trends as practiced at the Royal Academy. Siddal’s early work often addresses subjects from the poetry of William Wordsworth, Alfred Tennyson and their contemporaries, as well as the novels of Sir Walter Scott. While texts by these authors and others served as inspiration, much of her work seems to be strongly derived from her imagination.

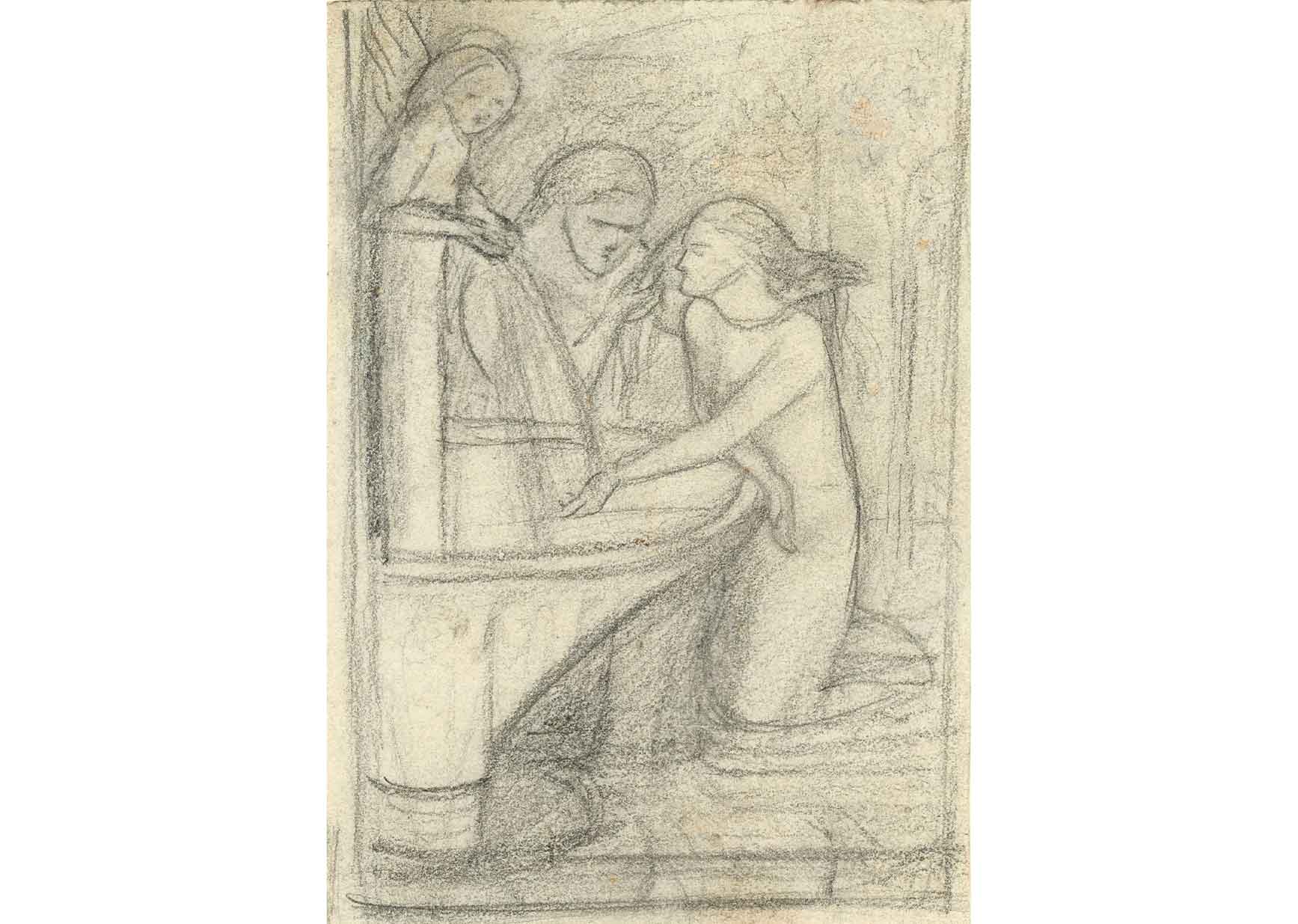

“La Belle Dame sans Merci” is the title of a poem by John Keats and was a great favorite among the young Pre-Raphaelites. Three of the drawings show a female figure accompanied by a man who gently draws back the hair of his companion. In the Delaware Art Museum’s version, as in one of those illustrated in the portfolio, there is also a fountain and a third winged figure, almost assuredly an angel. But upon close inspection, this figure might actually be part of the stone fountain, from whose hands the water emits. In terms of identifying the subject, I would suggest the key elements are the male figure’s gesture of drawing back the female’s hair; the existence of the fountain; and the angel, whether human or stone. Unfortunately, none of these details seem to relate to Keats’s poem. The strongest association would be a more general one, related to the stanza in which a knight’s meeting a fairy woman in a meadow is described:

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

We do have confirmation that Siddal was working on a composition inspired by Keats’s poem from a letter Rossetti wrote to his friend, the Irish poet William Allingham early in 1855 (23 January):

“She is now doing two lovely water-colours (from “We Are Seven” and La Belle Dame sans Merci”) – having found herself always thrown back for lack of health and wealth in the attempts she had made to begin a picture. [Letters, II: 55.4]

(Just to add further confusion, it is worth noting that no known watercolor of this composition has as of yet been identified). Nonetheless, this mention is helpful both as it gives some explanation of William Michael’s suggested title but also in providing a possible date for her work on this subject. (Siddal’s work was rarely dated, further complicating the unraveling of her creative output.)

But we are still left with the visual elements of Siddal’s drawing which just don’t seem to match up with Keats’s narrative. The obvious question then becomes, if not “La Belle Dame” then what?! Even William Michael seems to have been unsure as the inscription bearing the title includes a question mark. What else do we know Siddal was working on? Again, the archival record is limited but there are a few possibilities. We know, for instance, that there was a projected book of Scottish ballads which Allingham was editing for publication in the mid-1850s. Siddal and Rossetti were to provide accompanying illustrations. In preparation Siddal was given a copy of Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, two volumes of which survive with her name inscribed inside. That she was actively pursuing the project is confirmed in a letter Rossetti wrote to the artist, Ford Madox Brown,

“I think I told you that she and I are going to illustrate the Old Scottish Ballads which Allingham is editing for Routledge…She has just done her first block (from Clerk Saunders) and it is lovely.” [Letters I: 54.49]

Could this (and the other similar compositions) relate to one of these ballads for which no known illustrations have yet been identified?

Another possibility is that the drawings illustrate one of Lizzie’s own verses of which approximately 16 poems and a few fragments have been identified. (These have recently been collected, edited and published by Serena Trowbridge in a volume titled, My Ladys Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall, 2018). However, careful reading of these verses does not reveal any details which might lead to association with this particular composition.

And so, I end as I began, with a lovely example of Siddal’s drawing style but no further clarity on the subject as depicted. The search continues…

Margaretta S. Frederick

Annette Woolard-Provine Curator of the Bancroft Collection