For 150 years Americans have been fascinated with the medieval past. From Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court to HBO’s Game of Thrones, medieval fantasy realms have inundated literary and pop culture. The same is true in the medium of young adult fantasy literature and its illustration. The Delaware Art Museum’s upcoming Fantasy and the Medieval Past exhibit explores how American fantasy authors and illustrators have reinterpreted and reused the medieval past to populate their own fantasy worlds. The exhibit showcases 19th and early 20th century works from the permanent collection by the artist Howard Pyle in conversation with contemporary illustrations created within the past 20 years. These conversations allow visitors to experience the changing American understanding of the medieval world over the past century.

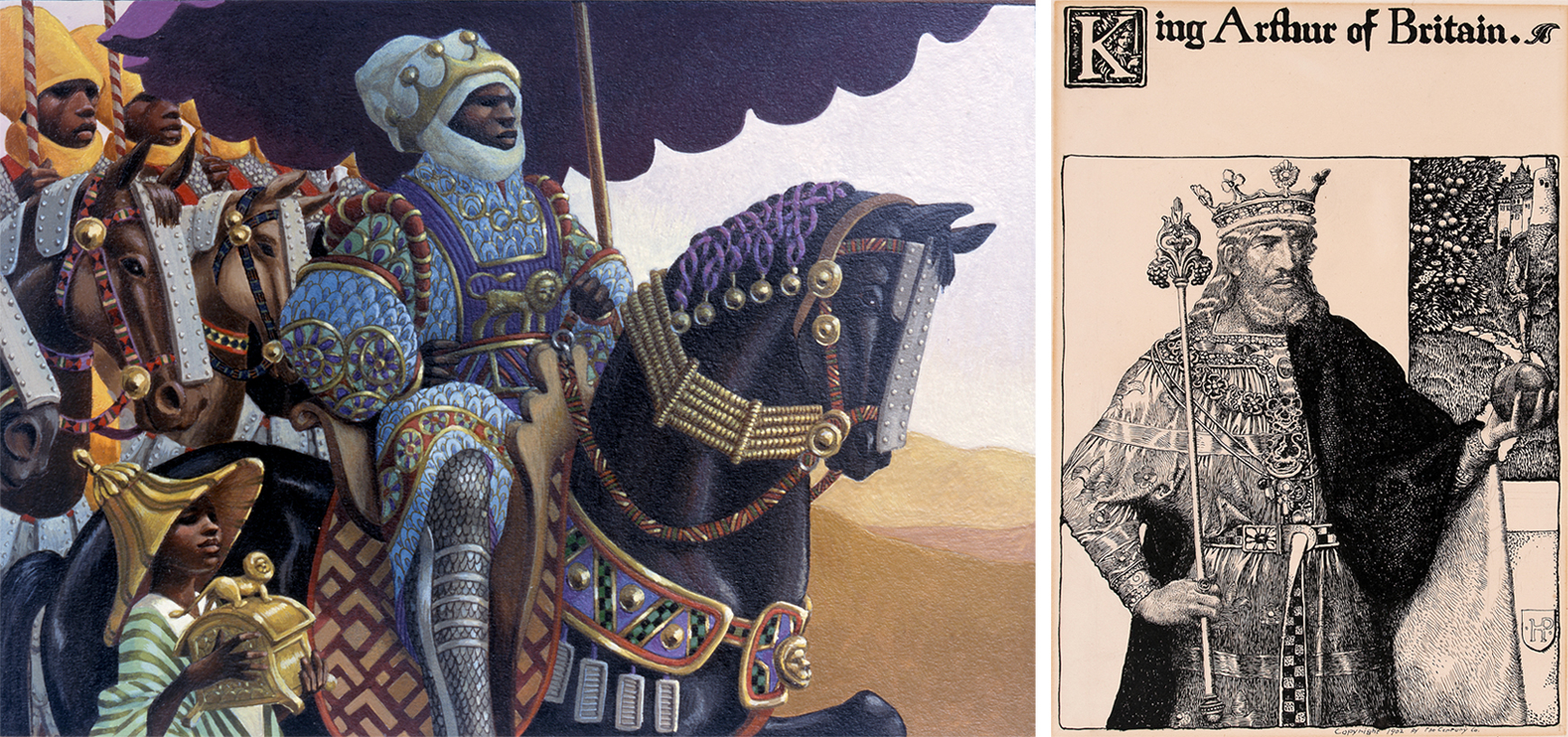

Left to right: Mansa Musa King of Mali, 2001. Cover illustration for Mansa Musa: The Lion of Mali, by Khephra Burns, (Gulliver Books, 2001). Diane Dillon (born 1933) and Leo Dillon (1933–2012). Gouache on Bristol board, composition: 6 x 8 1/2 inches, sheet: 10 x 12 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Diane and Leo Dillon. | King Arthur of Britain and decorated initial K with title and design, 1903. Illustration for “The Story of King Arthur and His Knights,” by Howard Pyle, in St. Nicholas, January 1903. Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/8 × 6 3/16 inches, sheet: 11 11/16 × 9 1/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Anne Poole Pyle, 1920.

Left to right: Mansa Musa King of Mali, 2001. Cover illustration for Mansa Musa: The Lion of Mali, by Khephra Burns, (Gulliver Books, 2001). Diane Dillon (born 1933) and Leo Dillon (1933–2012). Gouache on Bristol board, composition: 6 x 8 1/2 inches, sheet: 10 x 12 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Diane and Leo Dillon. | King Arthur of Britain and decorated initial K with title and design, 1903. Illustration for “The Story of King Arthur and His Knights,” by Howard Pyle, in St. Nicholas, January 1903. Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/8 × 6 3/16 inches, sheet: 11 11/16 × 9 1/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Anne Poole Pyle, 1920.

One such conversation is between Howard Pyle’s King Arthur of Britain and Leo and Diane Dillon’s Mansa Musa King of Mali. At the turn of the century Pyle authored and illustrated his own version of the Arthurian legends of King Arthur and his court. These books were meant for what we now consider a “young adult” audience, although the term did not exist at the time. Pyle envisioned a book that could straddle the generations, with parents reading to their children and both ages enjoying the story equally. Pyle’s King Arthur is a perfect representation of kingship as it was understood by Pyle and his contemporaries a century ago; White, male, and Eurocentric.

This understanding spoke more to 19th-century American biases than it did an accurate reflection of the medieval period. In reality, the medieval world was much more global and multicultural than previously understood. Extensive trade routes connected East Asia with the Middle East, the Middle East to Africa, and Africa to Europe. One such route crossed the Sahara Desert and brought precious materials such as ivory and gold from the Sub-Saharan Mali Empire to the Mediterranean Sea and then onward to the ports of Northern Europe. One of the most famous Mali kings was Mansa Musa. He was known for both his immense wealth and the hajj, or Islamic religious pilgrimage, he took to Mecca, crossing most of North Africa and showering gold on the city of Cairo along the way. In Leo and Diane Dillon’s illustration of Mansa Musa he is shown on this pilgrimage. The Dillons have cleverly represented Musa as a knightly figure on horseback. He sports chainmail armor and a western style crown on top of his head covering. For American audiences these features immediately identify Musa as a powerful, medieval, ruling figure, just like Pyle’s The Lady of Ye Lake. Both men are depicted gazing off into the distance as if they are contemplating complicated matters of state. By illustrating a book about the life of Mansa Musa, the Dillon’s have helped to educate young Americans on the true diversity and globalism of the medieval period.

Left to right: The Ironwood Tree, 2004. Cover illustration for The Ironwood Tree, The Spiderwick Chronicles Book 4, by Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, (Simon & Schuster, 2004). Tony DiTerlizzi (born 1969). Acryla gouache on plate-finish Bristol board, 14 3/4 x 10 3/8 inches, frame: 23 7/8 x 19 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Spiderwick Chronicles © Tony DiTerlizzi & Holly Black. | The Lady of Ye Lake and decorated initial T with title and design, 1903 from The Story of King Arthur and His Knights, by Howard Pyle (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903). Howard Pyle (American illustrator, 1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/16 × 6 1/4 inches, sheet: 14 5/8 × 11 1/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912.

Left to right: The Ironwood Tree, 2004. Cover illustration for The Ironwood Tree, The Spiderwick Chronicles Book 4, by Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, (Simon & Schuster, 2004). Tony DiTerlizzi (born 1969). Acryla gouache on plate-finish Bristol board, 14 3/4 x 10 3/8 inches, frame: 23 7/8 x 19 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Spiderwick Chronicles © Tony DiTerlizzi & Holly Black. | The Lady of Ye Lake and decorated initial T with title and design, 1903 from The Story of King Arthur and His Knights, by Howard Pyle (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903). Howard Pyle (American illustrator, 1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/16 × 6 1/4 inches, sheet: 14 5/8 × 11 1/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912.

Another visual conversation occurs between Howard Pyle’s Lady of the Lake and Tony DiTerlizzi’s The Ironwood Tree. Pyle’s Lady is depicted with all the traditional trappings of femininity. Her long hair is bound into two twists and she fingers one of the many necklaces around her neck. This gesture reveals the lady’s wrists which are encased in several jeweled bracelets. Here Pyle has created a woman who is the object of our gaze, not a participant in any action of the story. DiTerlizzi’s woman from the Ironwood Tree makes for an interesting comparison. This illustration was created for The Spiderwick Chronicles, a series of highly illustrated chapter books coauthored by DiTerlizzi and Holly Black. Although written a century later, The Spiderwick Chronicles are reminiscent of Pyle’s stories of King Arthur. They too were published as a serial in multiple volumes and contain extensive illustrations created in close conversation between the artist and the author. Unlike Pyle’s work, DiTerlizzi and Black have included in their books a strong female character whose actions are central to the story. In fact, she is the only main character in The Spiderwick Chronicles who is trained in combat and she often fights off enemy forces with her sword. In The Ironwood Tree DiTerlizzi has combined traditional elements of female medievalist representation with those demonstrating the strength and agency of this character. Her hair is bound similarly to Pyle’s Lady of the Lake and she is shown in a dress with jeweled necklaces and rings. Yet, her pose, eyes closed and a sword clutched to her chest, looks remarkably similar to medieval tomb effigies of medieval knights. This visual comparison elevates the character’s status from object of beauty to knightly protagonist. It additionally reflects a 21st century American interest in strong female characters, particularly in the young adult fantasy genre.

Regardless of the century, 20th or 21st, medieval-inspired creatures abound in fantasy illustrations. Some examples, such as dragons and unicorns seem plucked straight for a medieval bestiary, or book of beasts. Others, such as the gargoyle, were inspired by medieval architecture. Stories and Lies, illustrated by Ian Schoenherr for Kristin Chashore’s Bitterblue, shows a gargoyle with his tongue sticking out that is reminiscent of one of the famous gargoyles on the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Although medieval architecture does contain numerous examples of gargoyles, fantastic creatures, and other grotesques, this particular gargoyle was a creation of the French architect Viollet le Duc as part of his 1840s restoration of the cathedral after damage sustained during the French Revolution and subsequent political upheavals. All the same, this representation of a gargoyle has stuck in the minds of American audiences and has become a standard representation of a medieval inspired fantasy creature.

Fantasy and the Medieval Past runs from September 25, 2021 to January 31, 2022 in the Ammon galleries on the upper level.

Emily Shartrand

Join Emily for gallery talks in the special exhibition on October 16, and browse the novels illustrated by Tony DiTerlizzi, Leo and Diane Dillon, and Ian Schoenherr in the Museum Store.

Stories and Lies, 2012. Illustration for Bitterblue, Graceling Realm Book 3, by Kristin Cashore, (Dial Books for Young Readers, 2012). Ian Schoenherr (born 1966). Ink on paper, composition: 8 3/4 x 11 1/2 inches, sheet: 9 3/4 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Ian Schoenherr.