“Scores New Hit!” trumpeted one advertisement in the Cincinnati Enquirer. “An Artist-Humorist,” declared another. Both were positioned above a photograph of an attractive young woman with wavy bobbed hair and pearls around her neck. These advertisements announced the debut of a comic by Faith Burrows. Called “Flapper Filosofy,” the new feature was positioned as an extension of the artist’s persona: “After all, why shouldn’t she draw the snappiest of flappers and get off the cleverest of flapperisms? Doesn’t she know all there is to know about them? Because she is one. A beautiful blonde, young but not dumb.”

When these advertisements ran in 1929, Burrows was a 25-year-old woman with a public career and a modern sense of style. She was, in the parlance of the time, a flapper. And she gained fame for depicting this new type of woman in her daily comics “Ritzy Rosalie” and “Flapper Filosofy.” In the Jazz Age, women illustrators like Burrows presented evidence of a changing nation.

Time of Change

The 1920s was a decade of transformation and cultural dynamism in the United States. The end of World War I ushered in an unprecedented economic boom, which saw the emergence of consumer culture, technological innovations, and a relaxation of social norms, particularly for women.

For the first time in the nation’s history, more Americans were living in cities than in rural areas. Industrialization freed children from the workforce, allowing them to stay in school and attend college. Teens began spending more time with each other and less with their parents, creating a vibrant and visible youth culture where none had existed before. The affordability and accessibility of automobiles dramatically enhanced young people’s mobility and independence and marked the end of the Victorian era’s restrictive courtship system.

Fashion and Freedom

The fashion of the 1920s reflected this newfound freedom, with women embracing shorter hemlines and more comfortable clothing that offered greater mobility—especially dancing. The flapper emerged into this exciting, modern world, eager to shed old norms and embrace new freedoms. No longer content to be confined to the domestic sphere, flappers rattled traditional society by asserting their independence and determining their own destiny. Bold and unapologetic, these women epitomized the spirit of the Roaring Twenties.

A flapper was a young woman, known for her bobbed hair, visible makeup, daring fashion, and unconventional behavior. Her dresses were short, straight, and worn with knickers or “step-ins” instead of a corset or girdle. Her stockings were often rolled below her knees, and her shoes were flat or low-heeled. She challenged traditional societal and gender norms by engaging in behavior that was previously seen as unladylike, like publicly drinking, dancing, and smoking, and expressed her femininity and sexuality on her own terms.

Burrows’s flappers were paired with captions that spoke to the era’s concerns about the activities of young women. “While her old grandmother is becoming spiritually prepared the modern daughter is becoming spiritually preserved,” declared the text below an image of a young woman holding a cocktail glass. Another warned: “Nowadays about all they can say is ‘Sweet sixteen and never fell out of an aeroplane.’” Others depicted women playing sports and dining out.

Illustrating the Flapper

Print media in the 1920s played a pivotal role in defining, popularizing, and marketing the image of the flapper to women across the country. In books and magazines, John Held Jr. helped define the look of the flapper. Using a spare, linear style, Held depicted women bobbing their hair, dancing the Charleston, and reading Freud.

Left to right: John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, September 15, 1927. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, June 3, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Left to right: John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, September 15, 1927. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, June 3, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

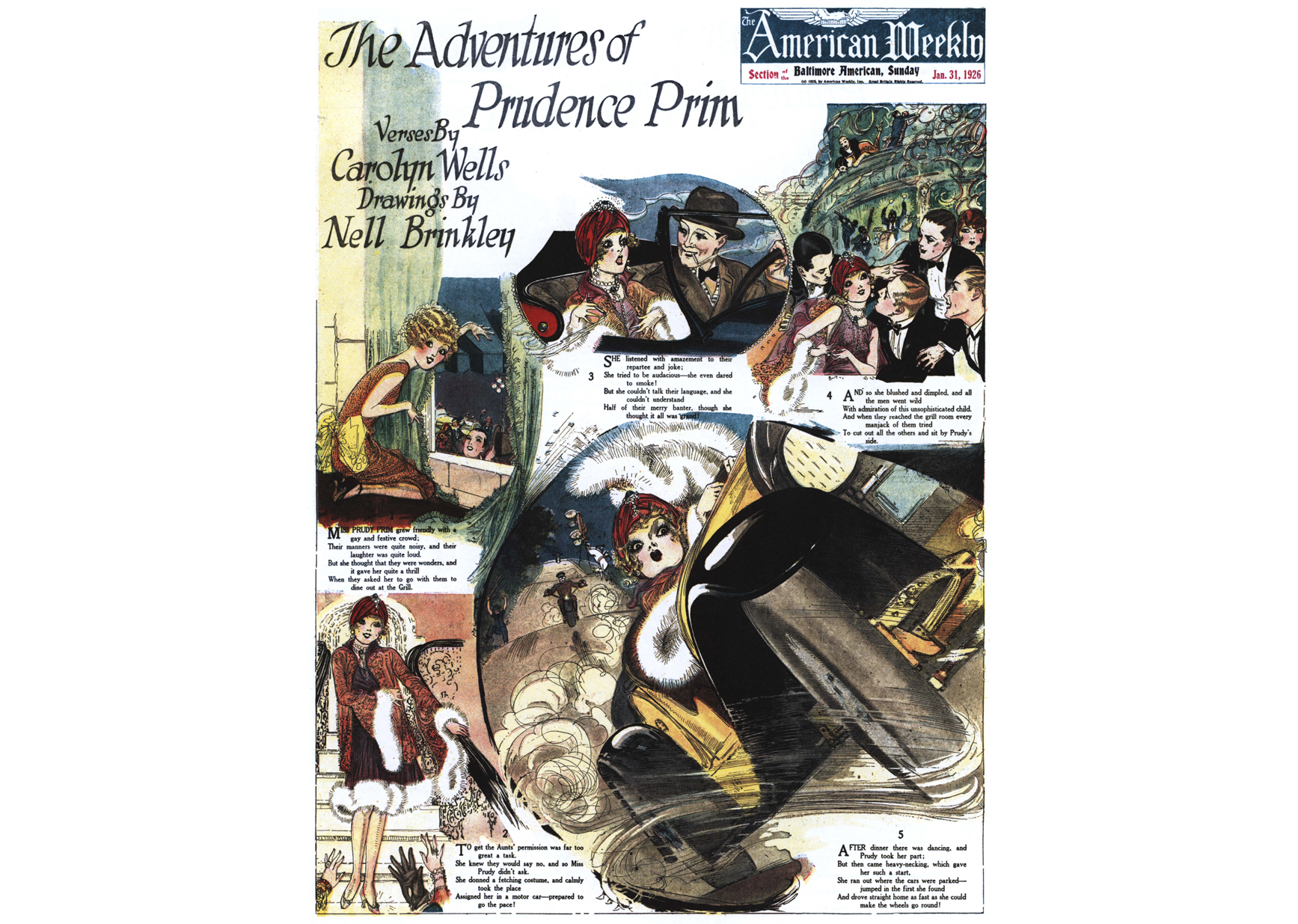

Nell Brinkley (1886-1944), The Adventures of Prudence Prim, from American Weekly, Chicago Herald and Examiner, January 31, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Nell Brinkley (1886-1944), The Adventures of Prudence Prim, from American Weekly, Chicago Herald and Examiner, January 31, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Working contemporaneously in a range of styles, women illustrators added to the flood of flapper imagery. Publishers hired established illustrators like May Wilson Preston to chronicle the lives of young women described in fiction by F. Scott Fitzgerald and other young writers. Even Nell Brinkley, a working illustrator since 1903, turned her focus to the flapper, producing the full-page cartoon, Prudence Prim. A stereotypical flapper, Prudence sneaks out to meet men, drive fast, and visit jazz clubs while wearing a variety of chic outfits.

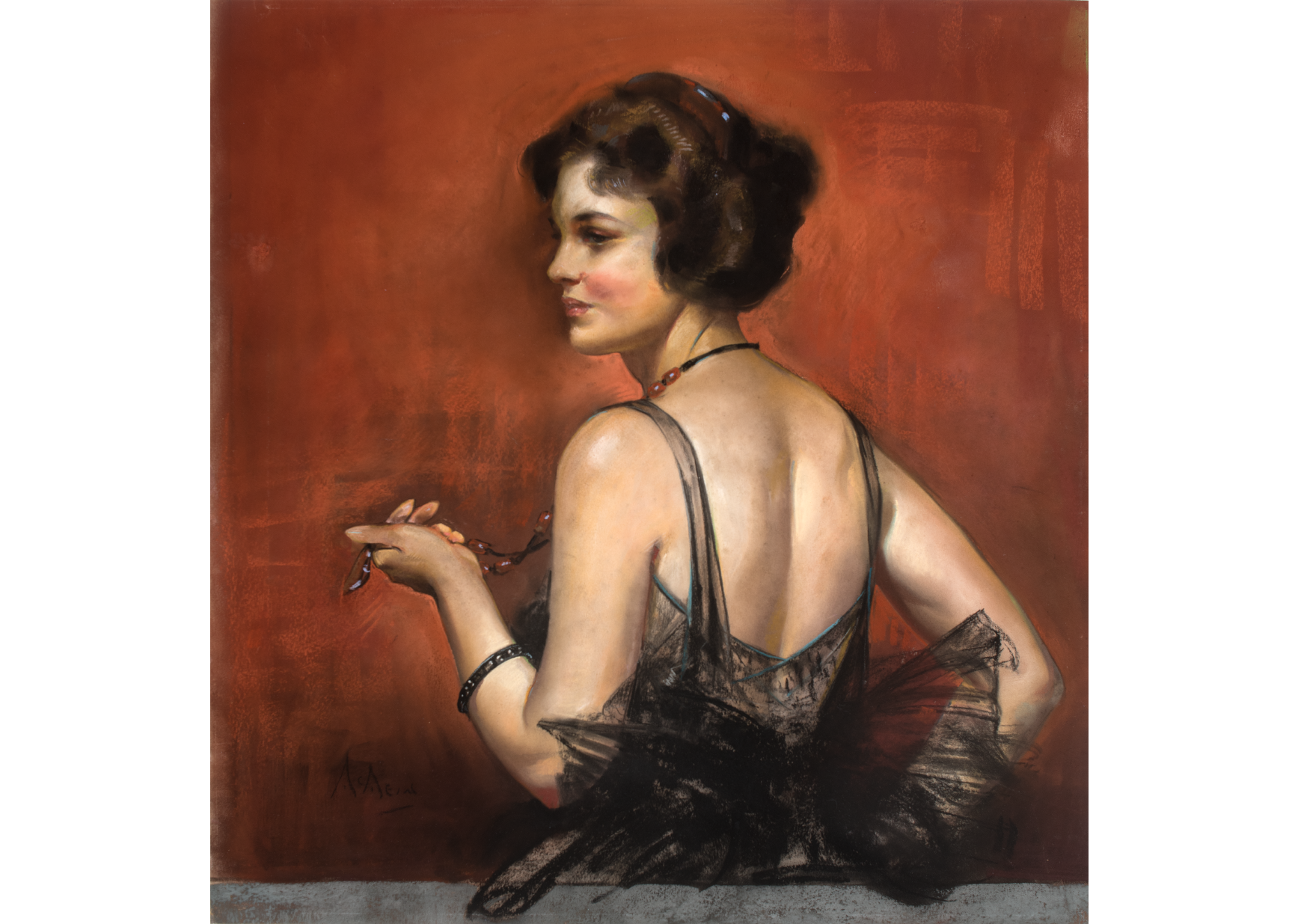

The Admirable Hostess, from Advertisement for Wallace Silver, published in The Saturday Evening Post, January 8, 1921. Neysa Moran McMein (1888–1949). Pastel on board, 30 1/8 × 28 5/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2022.

The Admirable Hostess, from Advertisement for Wallace Silver, published in The Saturday Evening Post, January 8, 1921. Neysa Moran McMein (1888–1949). Pastel on board, 30 1/8 × 28 5/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2022.

Neysa McMein, who emerged as a successful designer of advertisements and magazine covers in the teens, was invited to judge beauty contests and produce portraits of starlets. Newspaper features described her studio and her the unexpected advice she gave women—not to marry before age 30. Like Burrows, McMein was conflated with her subjects in these fizzy profiles, and writers mused about the artist’s resemblance to the beautiful women she illustrated.

In the hands of men and women, the flapper was both glorified and ridiculed—sometimes portrayed as a modern, liberated woman and sometimes as a silly, self-absorbed caricature—but always recognizable by her distinctive fashion and unconventional behaviors. By consistently highlighting the flapper’s style and attitude, print media helped solidify her role as a symbol of the Roaring Twenties, while reflecting broader social changes and the growing desire for personal freedom and self-expression.

This fall, the flappers of the Jazz Age and the women who illustrated them are featured in two exhibitions at the Delaware Art Museum. Jazz Age Illustration surveys the art of illustration between 1919 and 1942 and includes original work by Brinkley, Burrows, McMein, and others. The exhibition catalogue has an essay by scholar Victoria Rose Pass dedicated to youth fashion and style from the 1920s. Assembled from the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Flapper Philosophy: Modern Women in the Jazz Age focuses on flappers as they appeared on magazines, dust jackets, and sheet music. We had so much fun researching and collecting work for these shows. Please come and explore them both!

Rachael DiEleuterio, Librarian and Archivist

Heather Campbell Coyle, Curator of American Art

Librarian/Archivist Endowment Campaign Launched

The Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives is the driving force behind DelArt’s exhibitions and programs and is an essential resource for scholars, artists, and rare book enthusiasts. To preserve this important asset and invest in its future, the Museum just kicked off a $2 million campaign to endow the Librarian Archivist position. To date a quarter of the funds have been promised. With your help, we can preserve this treasured resource for future generations. Contributions should be directed to Joshua E. Liss, Advancement Officer, jliss@delart.org. Please direct questions to endowment campaign co-chair Margaretta Frederick, DelArt Curator Emerita, at mfrederick@delart.org.

Top, left to right: Nowadays about all they can say is “Sweet sixteen and never fell out of an aeroplane”, 1929 from “Flapper Filosofy,” Cartoon for King Features Syndicate, appeared in Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14, 1929. Faith Burrows (1904–1997). Pen, ink, graphite, and wash on stiff paper, 6 7/16 × 3 1/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2019. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. | While her old grandmother is becoming spiritually prepared the modern daughter is becoming spiritually preserved, 1929 from “Flapper Filosofy,” King Features Syndicate, appeared in Cincinnati Enquirer, September 25, 1929. Faith Burrows (1904–1997). Pen, ink, and wash on stiff paper, 6 3/8 × 3 3/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2019. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. | Flapper Filosofy [10-25], 1929 from Cartoon for King Features Syndicate, October 25, 1929. Faith Burrows (1904–1997). Pen, ink, and wash on stiff paper, 6 3/8 × 3 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2019. © King Features Syndicate, Inc.