Above, Fig. 1. Landscape Box (open), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

A box is a practical device, but artists have long seen greatness in its form. Some artists, like Donald Judd, celebrate the box for its simplicity. Joseph Cornell adopted the box given the practical role it served: its walls were boundaries that divided outside realities from the world he constructed within. Judd, Cornell, and the many other artists achieved their artistic success with boxes by playing upon their audience’s expectation of discovering mystery, mysticism, and magic within the unknown interior space.

Similarly, Po Shun Leong has mastered the dramatic potential of the box. A contemporary wood artist working in California, in 1988 Leong created what he refers to as a Landscape Box that is in the Delaware Art Museum’s collection today (Fig. 2). Solidly constructed out of glowing woods—cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa—it is a foot-and-a-half tall and, in its closed state, it seems to be a fine objet d’art, destined for tabletop display. The simplicity of line in its overarching bonnet and elegant side columns belie its actual complexity, but a gaping hollow at its center offers a peephole into another environment within. It begs to be opened. And it can be. In fact, each individual layer individually swings outward to progressively reveal a better view of the hidden sanctum at the core of the box (Fig. 1). Much like the pulling back of a curtain, the opening of the box reveals the stage set of Leong’s design. Embracing accessibility, Leong even incorporated a light into the design to better reveal the shadowy, unknown interior. Leong speaks of his desire for his viewers to touch and interact with his constructions. His mastery is not only the invocation of a wonderful mystery within his box but the permission he grants his audience to play, explore, and learn about that unknown.

Fig. 2. Landscape Box (closed), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

Fig. 2. Landscape Box (closed), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

Inside, the viewer discovers an interior that is like an illustrated glossary of architectural forms (Fig. 3). At the box’s central base, double archways lead to another set of interior archways, which are then succeeded by spiral staircases and columnar forms. On the level above, obelisks and broken columns point the way toward the main tier and the focal point: a propylaea or monumental gateway which frames a cavernous interior space. Peering inside, one finds this space is outfitted with even more staircases. In a strikingly simple uppermost level, a final staircase terminates in an enclosed, turreted space.

Fig. 3. Landscape Box (open) (detail), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

Fig. 3. Landscape Box (open) (detail), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

It comes as no surprise that Leong’s first career was not in woodcarving but in architecture. Trained in England where he was raised, as well as for a time under Le Corbusier in France, Leong ultimately settled and practiced in Mexico. Although his 1982 move to California marked a shift in his career, as well as his country of residence, he never abandoned his interest in architecture which is manifest in all of his wood constructions.

While Leong has invited us to physically explore a miniaturized world, this is hardly a dollhouse. Leong’s masterful recreation of architectural forms makes the space look familiar, but it fails to operate as a cohesive unit. The maze of staircases borders on the preposterous, both in the number of them and in their seeming inability to connect. Given the impossibility of navigating its constructions, the viewer is ultimately denied entrance into the sacred space of the box. Instead, there is a Surrealist element to the imagery. Leong seems to be invoking the prints of M. C. Escher who experimented with mathematical principles to play tricks upon the eye, as can be seen in one of his most famous lithographs from 1953 Relativity.

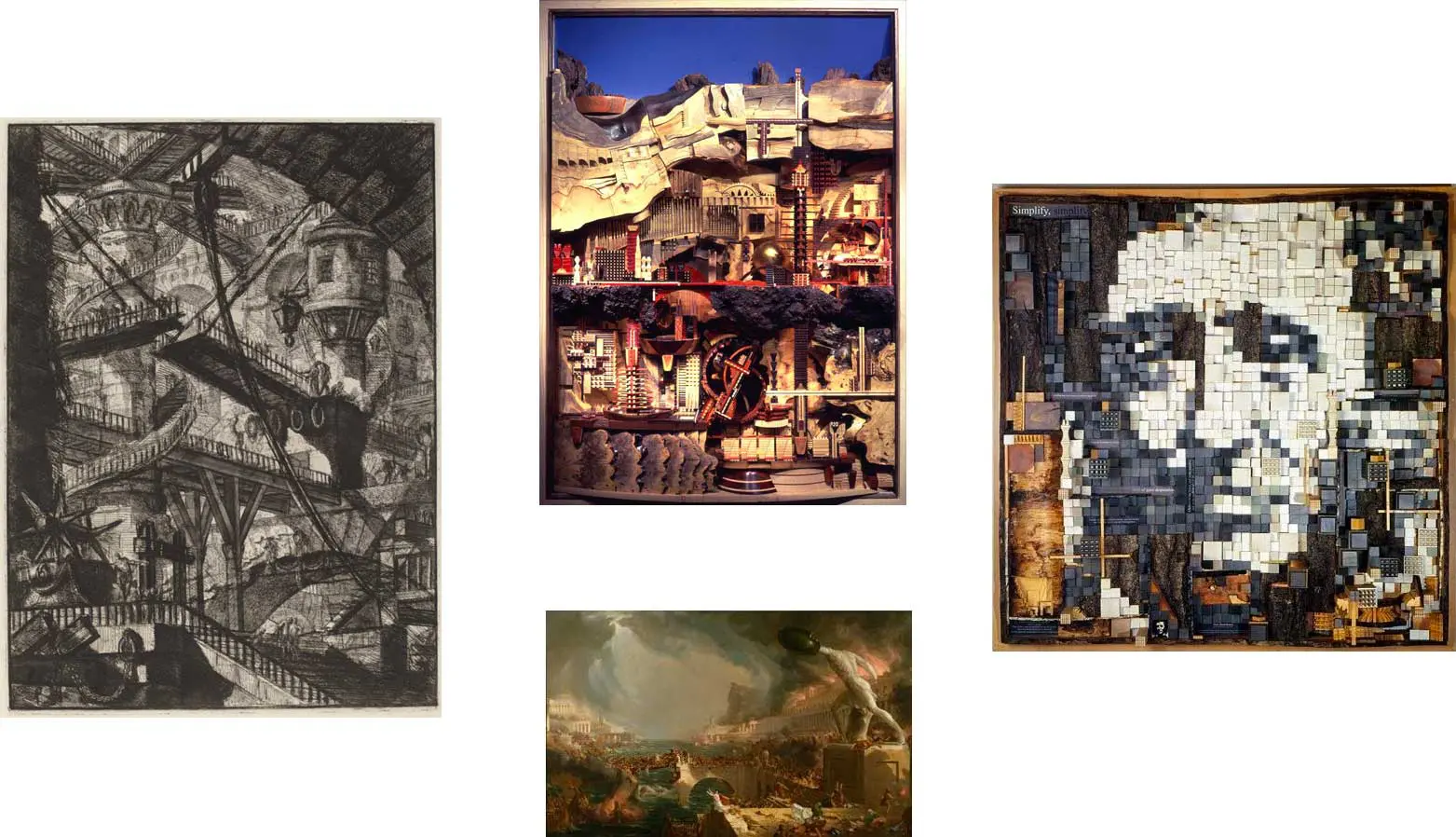

Escher’s print, and other work by Surrealists, took inspiration from the 18th-century printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi who famously rendered mazes of staircases in his series of 16 prints, Prisons (Fig. 4). Not only do Leong’s staircases recall Piranesi’s precedent, but his overall respect for architectural classicism parallels the other prints of Piranesi whose principal mission was to capture the Rome’s greatest architectural achievements centuries after they had fallen into disrepair. Piranesi celebrated the beauty in their time-worn aesthetic, even including tourists in his scenes who would pilfer spolia or decorative elements as souvenirs. Leong also chose to depict ancient architecture in its state of imperfection. He used the natural decay of the wood and sections with unfinished and jagged edges to suggest the erosion of time on the upper surfaces of many of his arches, including atop the pediment on the central propylaea. In such a modern, contemporary box, Leong is able to create a sense of venerable timelessness. In his other projects, too, Leong has taken inspiration from specific sites of the historical past: Pompeii, Petra, Mesa Verde (Fig. 5). These sites are constructed of stone and their grandeur and endurance is partially predicated on their materiality. Leong’s decision to recreate them in wood, a medium much more vulnerable to decay, could be an ironic reference to the inevitable destruction of any kind of art.

Clockwise, from left: Fig. 4. The Drawbridge, from Carceri, 1780s. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Etching, engraving, scratching, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. Fig. 5. Mesa Verde, 1994. Po Shun Leong. Buckeye burl woods, 55 x 40 x 9 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 7. Portrait collage of Henry David Thoreau, 2001. Po Shun Leong. Wood, 60 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 6. The Course of Empire: Destruction, 1836. Thomas Cole. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 63 1/2 inches. New York Historical Society, Gift of The New York Gallery of the Fine Arts.

Clockwise, from left: Fig. 4. The Drawbridge, from Carceri, 1780s. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Etching, engraving, scratching, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. Fig. 5. Mesa Verde, 1994. Po Shun Leong. Buckeye burl woods, 55 x 40 x 9 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 7. Portrait collage of Henry David Thoreau, 2001. Po Shun Leong. Wood, 60 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 6. The Course of Empire: Destruction, 1836. Thomas Cole. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 63 1/2 inches. New York Historical Society, Gift of The New York Gallery of the Fine Arts.

In many ways, an interest in classical decay is a characteristically American subject. Thomas Cole dedicated himself to a series on desecration and destruction, The Course of Empire, in which a city is born, reaches its height, and falls to ruin in five panels (Fig. 6). Cole intended these paintings as a commentary on society’s profligate indulgences, a cautionary warning against turning a blind eye to the future. While Leong’s box still has the sheen of a newly constructed piece, there is the subtle implication that as we manipulate the wood and play with the form, we are contributing to the slow process of its disintegration.

Leong’s interest in sustainability drove his artistic practice. Even before becoming a wood artist, his work in Mexico included designs for prefabricated housing, support of indigenous weaving practices, and the creative use of efficient materials such as fiberglass for chair designs. Most significantly, after becoming a wood artist, he has sought out recycled sources of wood. After a 1994 earthquake damaged a large collection of wood art and turnings, its owner offered the fragments to Leong who has since incorporated them into his art. In some cases, he recycles significant sources of wood in order to endow his objects with a special significance. In 2001, he was commissioned to create a portrait of Henry David Thoreau using the wood from fallen trees at Walden Pond (Fig. 7). And in the following year, Leong approached the renowned wood turner Bob Stocksdale and requested to use his scraps in order to create a “Cabinet of Curiosity.” Most importantly, Leong recycles his own work, incorporating sections of past projects into new ones. In a sense, his boxes become collaged assemblies of found objects like the art of Cornell or Louise Nevelson, among others. This practice of reuse is in-keeping with Leong’s investment in history. As old elements are creatively recombined, they bring their past meanings to a new context and the work becomes a repository of memories.

Leong’s environmental ethos compliments his liberal approach to defining who can produce his kind of art. Much like the permission—even mandate—he grants his audience to touch, he seeks to put his art in the hands of the broader public by facilitating their own production of it. As complex as his constructions appear, Leong emphasizes his lack of training and his use of the most basic tools and techniques, including the avoidance of joinery. He promises there are no dovetails here. Under the subheading DIY, his website offers directions on how to produce ancient ruins. And in 1998, a guide to constructing an array of his artistic boxes was published.

The Museum’s Landscape Box showcases a number of contradictions, something key to any art piece produced by an active and creative thinker. While its form cultivates an air of mystery, its artist also makes it accessible by embracing interaction with and even replication of it. Although it depicts historical subjects, it was made by someone invested in contemporary issues. Not easily categorized, the architect-turned-wood-artist Po Shun Leong realizes his unique visions and offers them to the world to explore.

Olivia Armandroff

2019 Alfred Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellow, Delaware Art Museum

Lois F. McNeil Fellow, Class of 2020, Winterthur Program in American Material Culture

Sources:

Leong, Po Shun. “Po Shun Leong: Floating Between Craft, Design and Cultures” filmed on June 18, 2016 at at the Craft in America Center, Los Angeles, CA, YouTube. Video, 43:00. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDEmQGin4UU.

Leong, Po Shun. PO SHUN LEONG: a portfolio of art in wood. Accessed August 5, 2019. http://www.poshunleong.com/.

Leong, Po Shun. “Po Shun Leong.” Collectors of Wood Art. Accessed August 5, 2019. http://collectorsofwoodart.org/artist/portfolio/152.

Ligate, Tony. Po Shun Leong: Art Boxes. Sterling Pub Co Inc. New York : Sterling Publications, 1998.