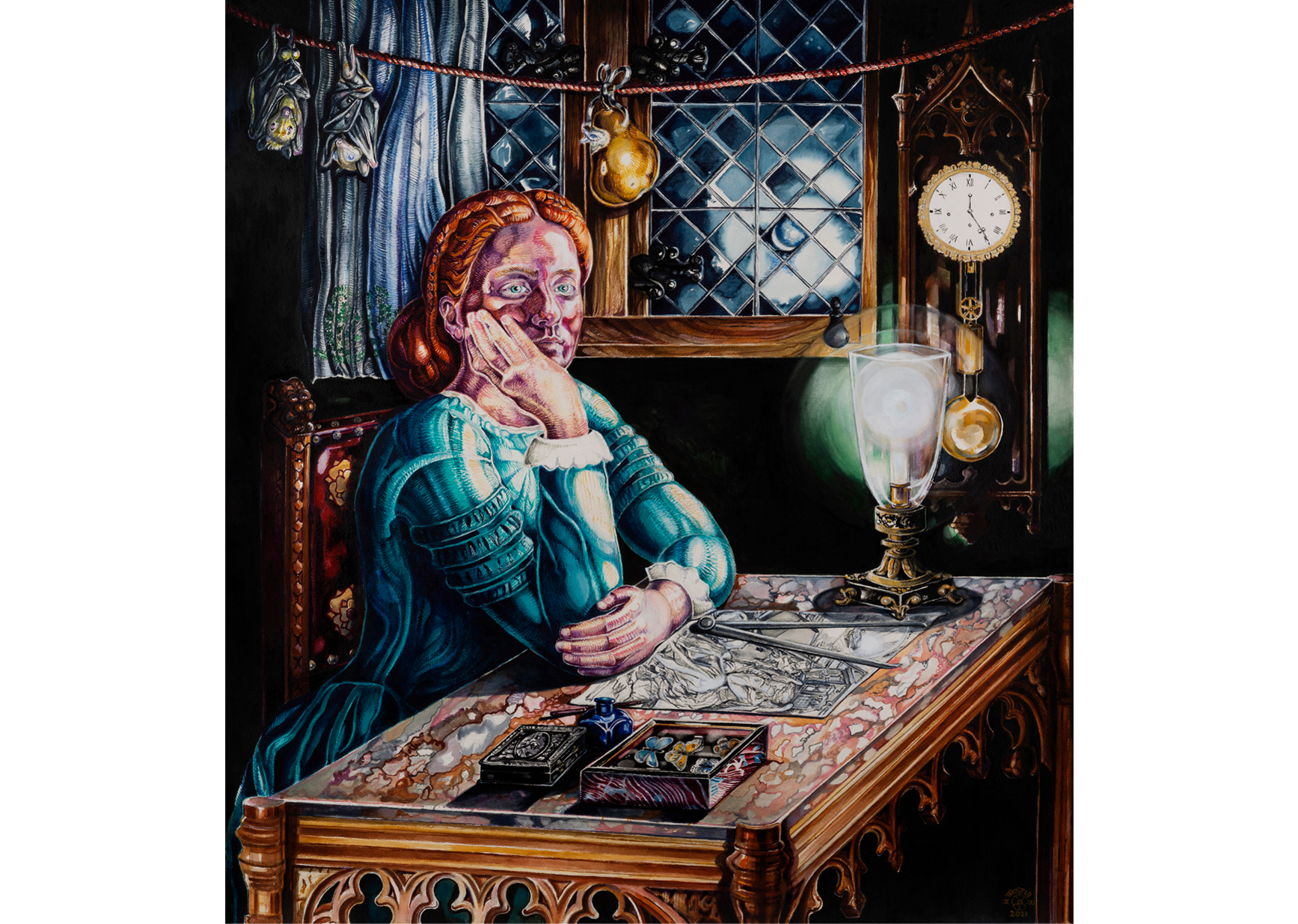

ILL. #1: “Elizabeth Siddal as Mariana,” 2021. Holly Trostle Brigham (born 1965). Watercolor on Arches paper, frame: 52 1/2 × 49 × 1 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Holly Trostle Brigham.

The moon hangs low at the casement window. The red-haired woman – as the painting’s title explains, Elizabeth Siddal as Mariana – stares out from her desk, pale eyes piercing with exhaustion and defiance. Her hands cup her chin and elbow, a posture which echoes the figure from Dürer’s Melancholia, which she has spent the night copying. That figure sits with a measuring device, and the drawing measures her mood, is measured by the calipers that rest atop it, folds into the name of the play – Measure for Measure – that gave rise to the painting’s subject. But, as its creator Holly Trostle Brigham assures me, this nocturnal sketcher is no longer waiting. She has made it through the night, supported by inspiration from another artist – and now she looks up, because someone has come in.

Brigham’s painting is also inspired by another artist: Elizabeth Siddal. As Siddal did, Brigham picks apart a Tennyson poem and reimagines it in watercolour. Mariana was not depicted by Siddal (as far as her surviving corpus shows), nor was she a figure for whom Siddal posed, though both Siddal and Mariana were painted by Siddal’s Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries. This space lets Brigham make the subject her own, exploring contemporary and personal resonance alongside Siddal’s methods. Brigham’s Mariana was painted in the moated grange of lockdown, working through loneliness towards an uncertain future. But, though she may be aweary, Siddal-Mariana does not disappear in death. In the inspiration her creative work offers Brigham, and the new exhibition which draws on her practice, she wakes again.

I Wake Again: Holly Trostle Brigham on Elizabeth Siddal, opening at the Delaware Art Museum on February 26th, 2022, explores the ‘two voices’ of the contemporary feminist painter and the chaotic Victorian artist-poet. Elizabeth Siddal as Mariana appears alongside an artist’s book intertwining depictions of Siddal’s life with poetic responses by Kim Bridgford, a textile tangling Siddal’s initials into foliage, and a screen painted with the heroines of Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Sometimes Brigham’s work imagines the artist-poet at her easel, or alongside her husband and occasional collaborator Dante Gabriel Rossetti, or rapt in a book. Elsewhere, Brigham evokes Siddal as a precedent, making something after the fashion of a piece Siddal made, or could have made. The Faerie Queene screen applies Siddal’s medievalist methodology to a new literary source, whilst the box containing the artist’s book pays homage to the jewel box Siddal decorated for Jane Morris.

Brigham’s engagement with Siddal – artist to artist, recognising shared techniques and imaginative complexity – fascinates me, partly because I work in a similar way. My work is also inspired by Siddal’s creative practice, drawing on her disruptive impulses to produce queer readings of her art and poetry. I met Brigham whilst on the long-delayed, thoroughly wonderful Amy P. Goldman Pre-Raphaelite Fellowship at the University of Delaware and Delaware Art Museum, gathering research for my PhD thesis on Siddal.

So what is Siddal’s story? She was born in London in 1829, on July 25th – a birthday she shares with Brigham. In 1849, she showed her drawings to Walter Deverell senior, principal of the Government School of Design, and modelled for his son. Deverell junior was close with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, among whom Siddal found more modelling work. Her early artwork The Lady of Shalott (1853) shows Siddal altering the spelling of her surname – a common practice amongst Pre-Raphaelites embracing a new artistic identity. Siddal’s works on paper attracted John Ruskin’s patronage, allowing her to purchase paints to produce medievalist watercolours like Clerk Saunders and Lady Clare (both 1857). In 1857, her work was exhibited and purchased in Britain and America – whilst Siddal broke from the overbearing Ruskin and moved to study art in her ancestral Sheffield. Her movements are less well-known away from the Pre-Raphaelites. In 1860, she married Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and her known art production resumed: she planned an illustrated book with Georgiana Burne-Jones and helped decorate William Morris’s Red House. She became addicted to laudanum in or around 1860, suffered a stillbirth, and died of a laudanum overdose on February 11th 1862. She also wrote poetry, in largely untitled manuscripts which remained private until after her death.

The Delaware Art Museum has a rich Pre-Raphaelite collection, including some Siddal works. Brigham has long admired Pre-Raphaelite art, and brings her art-historical background to bear on her creative interpretation of this complex, jewel-toned, deeply literary artistic legacy. In the world of the Pre-Raphaelites, the hierarchy of media is unsettled, and books, decorative arts and easel paintings intertwine in a creative conversation. It’s a dynamic which informs the fascinating interplay between the pieces – from paintings to textiles to tiles – in Brigham’s exhibition.

Researching Siddal amidst the Pre-Raphaelites has, as Brigham explains, been an educative experience. She relishes Siddal’s complicated compositions, her ambition, her dynamic lines and diagonals, her penchant (which Brigham shares) for using herself as a model. Brigham has discovered new texts through Siddal’s unusual subjects. Indeed, both artists’ works affirm the power of text – which Siddal espouses in her literary source material, and Brigham explores through her artist’s books. For Siddal, words are ripe for pictorial reimagining; for Brigham, they clarify her art’s feminist message. Though few of Siddal’s personal papers survive, leaving little record of her discussing her work with others, Brigham is eager to start conversations – to reward this jet-lagged scholar’s aweary ‘Why Mariana?’ with talk of measures and Melancholia. Brigham’s work, like Siddal’s, offers viewers this chance to be curious, to discover, to delve into a myriad of small details and be rewarded tenfold for your interest.

I started with a painting, and I end with a box, patterned with the Four Seasons and the artist’s EES. Inside, Brigham has placed three things. There are pages from another Tennyson poem, a sketchbook – the artist’s book – and a bottle of dried pigment. There’s potential – for the poem to become a sketch, for the sketches to become paintings, for the pigment to become the paint – but there’s also the resources to realise this potential. The inspiration, the materials and the production. Here, and throughout, Brigham pays homage to Siddal as a creative force, whilst her own creativity shines through in every brilliant, meticulous detail. The act of making art is foregrounded and celebrated – as a wonder, a comfort, a reawakening.

Nat Reeve

‘Nat Reeve is a PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London, working on queer reading the art and poetry of Elizabeth Siddal. They are also a novelist: their debut Neo-Victorian novel Nettleblack will be published in 2022 by Cipher Press, and is available for pre-order. Nat was the 2020/2021 Amy P. Goldman Pre-Raphaelite Fellow.’

With fervent thanks to Holly Trostle Brigham for a wonderful discussion, and Margaretta S. Frederick and Mark Samuels Lasner for their covid-defying patience with the Fellowship.

I Wake Again: Holly Trostle Brigham on Elizabeth Siddal is on view at the Delaware Art Museum February 26 – May 29, 2022. Join Nat and Holly for a virtual Art Chat on Friday, March 3, 12 p.m. EST.