I can’t recall what made me wander into James Kochan’s booth at the Delaware Antiques Show. It was almost certainly an illustration—probably something that reminded me of Howard Pyle—but another small watercolor in the corner caught my eye. It was more modern than Pyle, but well composed and full of action. Moving up close, I encountered a deftly handled watercolor by Frederick Coffay Yohn illustrating the Harlem Hellfighters fighting in Séchault, France, in 1918.

The 369th Infantry Regiment, commonly referred to as the Harlem Hellfighters, was one of the first African American regiments to serve with the American Expeditionary Force. During World War I, the 369th spent 191 days in frontline trenches and suffered 1,500 casualties, serving primarily with French troops due to segregation in the U.S. Army. The regiment was celebrated in newspapers and magazines published by and for Black audiences, but original illustrations of the regiment from the time are rare. Strolling through the Antique Show, I had found something I didn’t know I was looking for, and the Museum acquired the watercolor.

About a generation younger than Pyle, Yohn was renowned for his depictions of battles from the American Revolution to World War I. In October 1918, Yohn’s battlefront drawings appeared in a special section in Scribner’s Magazine. The Harlem Hellfighters image wouldn’t have been completed in time for this issue, and although it looks like a finished illustration, I haven’t yet found evidence of its publication elsewhere. The 369th Regiment was never pictured in Scribner’s war coverage and only received one mention—which referenced the regiment’s band—in the magazine between 1917 and 1919. In this era, Black figures were rarely represented in the mainstream magazines which catered to white middle- and upper-class readers. When African Americans did appear, it was generally in positions of service, rather than as war heroes. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Black press developed to tell stories by and for African Americans, flourishing in the Harlem Renaissance that followed the war.

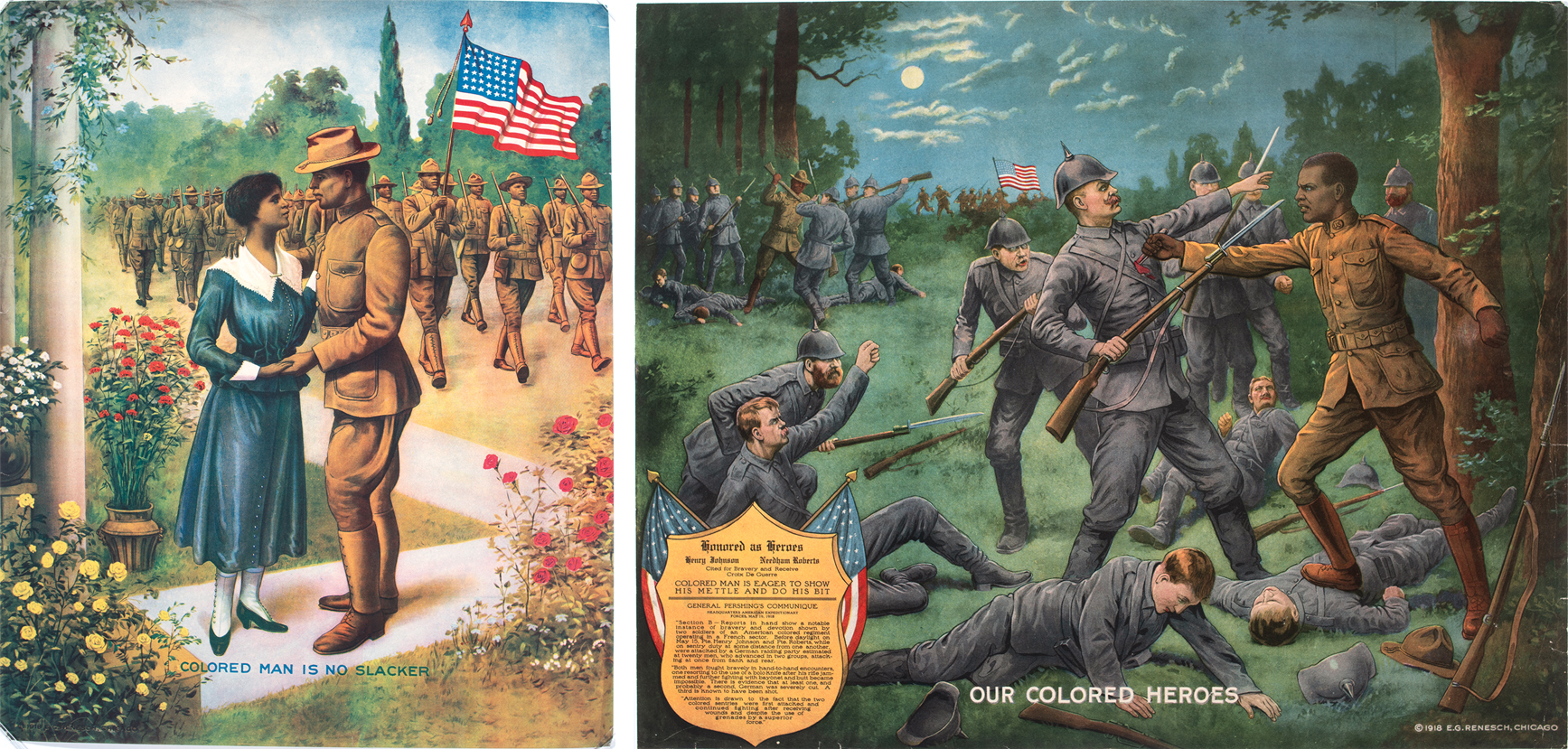

Right: Our Colored Heroes, 1918. E.G. Renesch (1879–1957). Chromolithograph, 16 x 19 15/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2024.

This divided media landscape may account for the production of two other recent acquisitions—recruiting posters that specifically targeted African Americans. In one, a young man says farewell to his sweetheart before joining a corps of marching soldiers proudly carrying the American flag. The text reads, “Colored man is no slacker,” adopting a popular term used to describe young men who did not enlist.

The second celebrates the heroics of soldiers Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, members of the Harlem Hellfighters who heroically defended the Allied lines from 20 Germans raiding on the night of May 15, 1918. This is an unusual approach for a recruitment poster—celebrating the heroics of specific servicemen. These posters may have appealed to young Black men hoping that honorable service would undermine racism and increase opportunities after the war. While little is known of the artist, Renesch was a white man, like the vast majority of illustrators who produced war posters. These two posters—one purchased at auction and the other a generous gift—enhance the upcoming exhibition and add an important facet to DelArt’s extensive collection of World War I posters.

I am excited to share these recent acquisitions and the story they tell about the Harlem Hellfighters, alongside over 200 works of art featured in Imprinted this year.

Top: The Harlem Hellfighters Capture Séchault, 25 September 1918 . Frederick Coffay Yohn (1875–1933). Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper, 8 ½ x 12 ½ inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2022.