What happens when you place two unrelated works of art from different continents, centuries, movements, and artistic backgrounds next to one another on a gallery wall? Something magical it seems. Even when works of art have a 150-year gap in their creation and stylistically come from different eras, relationships can form between them if they connect visually or tell similar stories that strengthen their bond.

The way that a museum is able to share these stories with the community is through the practice of collecting. This idea has become the basic premise of the upcoming show Collecting and Connecting: Recent Acquisitions, 2010-2020. Over the past ten years, the Museum’s curators have worked hard to expand each of the collections (American Illustration, British Pre-Raphaelites, American Art to 1960, Contemporary Art, and the Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives), which has resulted in the acquisition of more than 1,500 new works. Always keeping the existing artwork in mind, the curators have actively shaped the collections to emphasize stories of women, artists of color, LGBTQ+ communities, local artists, and works which express innovative creativity.

Viewing artwork is an interpretive and subjective experience because everyone brings a different perspective to the table. This is the main reason why the works that will be shown in Collecting and Connecting are organized into groups based on visual, contextual, and emotional connections instead of by collection or chronological order. This way, we hope to create juxtapositions with artwork which extend past the barriers of time, movement, collection, country, style, or medium, and focus on what viewers physically see in the moment.

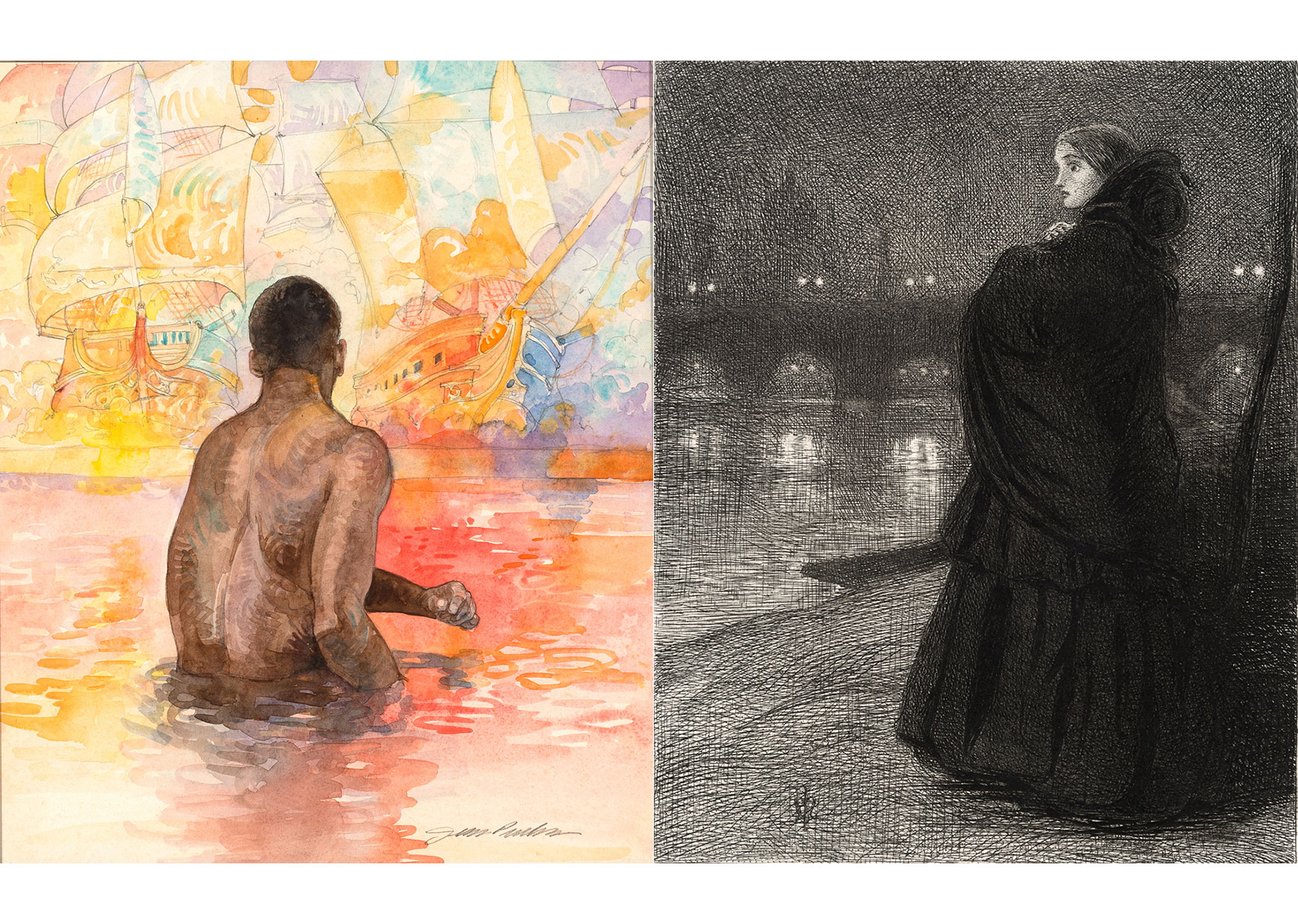

When beginning to plan the exhibition, it was difficult not to organize by collection, chronological order, or overarching theme, which is how most shows that feature recent acquisitions are laid out. The organization by theme was appealing, but felt forced, and we wanted to give the audience as much freedom for interpretation as possible. This quickly evolved into what the basis of the show will be: creating strong relationships between unrelated works through interesting juxtapositions. After looking through all 1,500+ works, a few significant relationships began to appear, one of which was that between Jerry Pinkney’s Cover Study for The Old African,” 2005, and John Everett Millais’s The Bridge of Sighs, 1857.

Take a moment to view these two works. With no background or context, what are you seeing? What stories do you think they are telling independently? What story do you think they tell together?

Pinkney, a successful illustration artist, created this watercolor as a study for the cover of Julius Lester’s children’s book, The Old African, published in 2005, which tells the reimagined legend of the Old African, a slave who uses mystical powers to free and lead a group of his fellow slaves on a journey back to their homeland of Africa.[1] Pinkney illustrated the entire book, creating stunning visuals that revealed both the horrors of slavery and the magic of hope in a way that still engages and educates readers of all ages. Expressing his desire to tell stories through images, Pinkney states on his website, “I’ve made a concerted effort to use my art making to examine as well as express my interest in Black history and culture—the tragedy, resilience, courage, and grit of African American people in their contributions to this country’s development. This deep dive into my own roots also bridged my interest in other cultures and histories of people who have been marginalized.”[2]

Both this study and the final version feature the main character, the Old African, gazing out into the ocean horizon where ships are sailing by, presumably on their way to deliver or pick up slaves. The ships are deceptively colorful albeit their ominous nature. Pinkney chose to depict a scene that sits in the interim of the story’s action—between fleeing the plantation and arriving in Africa. The energy and emotion of a scene that shows the Old African in contemplation is palpable. Pinkney filled this moment with vibrant colors to possibly represent the spiritual nature and magical abilities of the Old African, but also to express an optimistic attitude that good will conquer evil. The Museum acquired this piece in 2018 for a number of reasons, one of which was its visual relationship to Howard Pyle’s colorful pirate works, such as An Attack on a Galleon (1905), a work already in the Museum’s collection.

In 1857, John Everett Millais etched the scene in The Bridge of Sighs based on the poem of the same name by Thomas Hood, which was originally published in 1844. The poem tells the story of a woman driven to suicide because of her status as an impoverished, homeless, vagrant living on the streets of Victorian London. In this print, Millais depicts the woman contemplating her decision. The common archetype that developed in Victorian England of the “fallen woman” was a woman who was cast out by her family because of a sexual transgression and/or who lacked opportunities provided to men, such as a proper job or housing.[3] This woman, according to social myth, would then go to the city where she became a prostitute, eventually throwing herself off of a bridge out of guilt, and then literally falling to her death.[4]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and related artists chose to depict confrontational scenes of modern life, contrary to the Royal Academy’s preference for sentimental genre scenes. The fallen woman was depicted by many Victorian artists in various stages of their plight, with many artists seeking to arouse empathy in the viewer for the difficulties a modern woman faces. Many artists also sought to warn their audience about what can happen if a woman is led astray from the social norm. In Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s unfinished Found (1854), the woman has already fallen but is being rescued, whereas in George Frederic Watts’s Found Drowned (1848-50) the woman has already completed suicide by jumping from a bridge. Millais’s work, however, shows a woman between these two possible endings, not yet rescued but not yet having lost all hope. It is a moment of anticipation in which the viewer can imagine the woman turning her life around and recovering or suffering the same fate as many others.

While planning and selecting works for the exhibition, there were a few visual relationships that we identified right from the start and used as the basis for creating other connections between work of art. Even when we did not have a clear idea of how this show would be presented, we knew that the relationships we were seeing were important and shared the story of the Museum’s collections in a different way. It has been a fascinating exercise to look at the museum’s 1,500+ recent acquisitions and see how much a work from 1857 and one from 2005 can tell the same story or have a very similar composition.

Like Pinkney’s study, Millais’s print also shows a moment of contemplation and anticipation. Both the Old African and the fallen woman have been horribly abused and mistreated by society at large, abandoned and left to their own devices. Whereas the Old African chooses to see hope and fight for freedom, the fallen woman sees endless despair and will ultimately choose to accept her tragic fate.

Compositionally, the figures in Pinkney’s study for The Old African and Millais’s The Bridge of Sighs sit on opposite sides of their framed scenes and face opposite directions. The woman in Millais’s work is in standing on the right and gazing out on the environment to the left with her face open to the audience, most likely because she has nothing to hide anymore. Alternately, Pinkney’s Old African stands waist deep in the water on the left, while looking out on the ships and expanse of ocean to the right and is turned away from the audience, adding to the mystery of the character. Pinkney’s work is a bright, colorful day scene, whereas Millais’s is a black and white, shadowed nocturne. Although the two artists lived more than 100 years apart and in different continents, they each used their artistic talents to meaningfully share a story that would educate, create empathy and understanding, and potentially have an impact on their community. Cover Study for The Old African and The Bridge of Sighs make for an unlikely pairing, but have a deeper visual and contextual relationship that instantly made them a vital part of Collecting and Connecting: Recent Acquisitions, 2010-2020.

Collecting and Connecting: Recent Acquisitions, 2010-2020 will run from March 13 to September 12, 2021, in the Anthony N. and Catherine A. Fusco Gallery, with additional recent acquisitions installed and highlighted throughout the Museum and Copeland Sculpture Garden.

Caroline Giddis

2020 Alfred Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellow

MA in Art History, Savannah College of Art and Design

Above, left to right: Variant of or study for the cover of “The Old African”, 2005, for The Old African by Julius Lester (New York, Dial Press, 2005). Jerry Pinkney (born 1939). Watercolor and graphite on paper, 12 1/4 × 10 3/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2018. © Jerry Pinkney. | The Bridge of Sighs, 1857. John Everett Millais (1829-1896). Etching, plate: 4 ½ x 3 ½ inches, sheet: 16 ¾ x 11 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2015.

Sources/Endnotes

1. Publisher’s Weekly, “The Old African, Julius Lester, Author, Jerry Pinkney, Illustrator,” book review, Publisher’s Weekly, October 24, 2005, https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-8037-2564-5.

2. Jerry Pinkney, What’s New?, JerryPinkneyStudio.com, 2019, accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.jerrypinkneystudio.com/frameset.html.

3. Linda Nochlin, “Lost and Found: Once More the Fallen Woman,” in Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 1st ed., (New York: Harper and Row, 1982), 226-229.

4. Lynn Nead, “The Magdalen in Modern Times: The Mythology of the Fallen Woman in Pre-Raphaelite Painting,” Oxford Art Journal 7, no. 1 (1984): 30-32.