“My art serves as a reflection, in poetic images, of a total experience. There is something in it of tears, laughter, courage, awareness, and a zestful vigor which moves more definitely into the future than the promise of a new day.”1

Individuality and Community

James E. Newton firmly believed that an artist’s personal experiences shape their artistic production. The power of Newton’s individual and subjective experience is clear in his expressive, and often enigmatic compositions. Whimsical titles such as The Love Machine, Piggly Wiggly, and Miki-Mous Thyme suggest a sense of humor and playfulness that is echoed in some of his later character drawings. In works such as They Came Before Columbus VI and American Sixties II, Newton mobilized his artistic practice and distinct perspective to comment on wider social and cultural issues. Newton merges abstraction and articulated imagery to produce works that both convey the artist’s lived experience and allow for viewers’ unique interpretations.

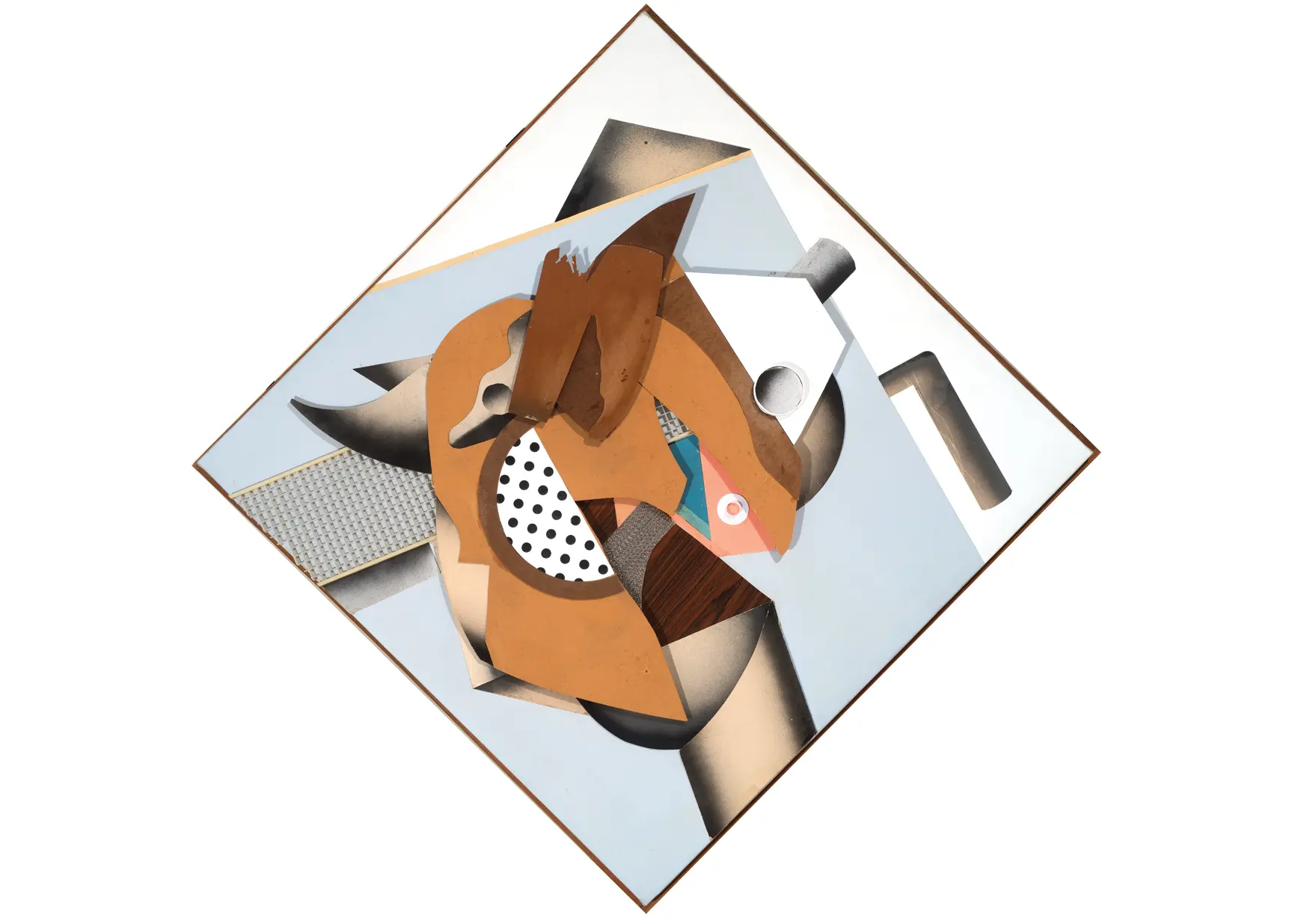

Left: American Sixties II, c. 1970. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media assemblage, 49 5/8 x 34 5/8 x 4 1/2 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: They Came Before Columbus VI, 2007. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Ink and acrylic on board, 12 × 16 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Left: American Sixties II, c. 1970. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media assemblage, 49 5/8 x 34 5/8 x 4 1/2 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: They Came Before Columbus VI, 2007. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Ink and acrylic on board, 12 × 16 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

This productive tension between the individual experience and community perception can be seen in three of Newton’s early pieces: Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Mausoleum of Lazarus, and Don Quixote. All three works originated during Newton’s time as a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and were included in his MFA thesis in 1968. They represent Newton’s early experimentation with figuration. In Hunchback of Notre Dame, a medley of shapes in ochre, crimson, white, and pale yellow jostle against one another. Thick, black lines both serve to delineate and connect the precarious ovals, blocks, and rectangles. A face and limbs emerging from the sketchy jumble. Each work is a collage, a compilation of disparate elements to create a whole picture. The figures pictured in each relate to storied characters—Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo, the biblical Lazarus, and Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote—who were in some way marginalized by society or considered outcasts. Using bold shapes and thick, gestural strokes of color, Newton not only gives form to the external appearance of these figures, but also conveys inner feelings and experiences. His distorted, graphic style conveys that these characters are both seen and unseen. They are distinguished by their differences, and consequently ignored or excluded from society because of them. Newton’s works outwardly express “private matter[s] of intuition and subconscious.”2 In doing so, they urge viewers to look beyond superficial appearances and empathize with the figures’ inner struggle.

Left: Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 40 × 36 1/4 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Middle: Mausoleum of Lazarus, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on board, 31 3/4 × 24 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: Don Quixote, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 23 × 15 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Left: Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 40 × 36 1/4 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Middle: Mausoleum of Lazarus, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on board, 31 3/4 × 24 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: Don Quixote, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 23 × 15 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Resilience and Resourcefulness

In reflecting on his childhood, James Newton humorously recounted his early realizations of racial difference as the sole Black student in his kindergarten classroom: “I was shocked that all these people had white legs, and I went home to my mother, and I said, ‘Mom, they got a white leg disease’.”3

As a young, Black man growing up in the late 1950s and 1960s, James Newton witnessed and experienced different treatment because of race. While serving as a military policeman, Newton spoke out about Black colleagues’ ineligibility for promotion. In 1966, he integrated the Fine Arts program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill becoming the first African American graduate student in the department “before any Black basketball players were there.”4 While coming home from his work study position, he was arrested by the Chapel Hill police for impersonating a student. Newton also recalled a similar environment of racial hostility when he began teaching at the University of Delaware in the early 1970s.

Piggly Wiggly, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media, 42 × 41 1/4 × 7 inches, support: 57 1/2 × 56 1/2 × 7 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Piggly Wiggly, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media, 42 × 41 1/4 × 7 inches, support: 57 1/2 × 56 1/2 × 7 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Through his artistic practice, Newton grappled with these patterns of harassment and marginalization and found a creative outlet for his lived experience. He recalled that during his MFA period, he could not afford new paints or tools so he “became a scavenger,” retrieving discarded paint tubes and collecting castoff materials to incorporate into his art pieces.5 Newton created Trio using such materials. The thin washes of pigment created a layered colorscape and reflect Newton’s ingenuity. This kind of resourcefulness and resilience characterizes his body of work. In Piggly Wiggly, for example, biomorphic shapes of cut Masonite, colored paper, plastic cubes, sheets rock, and pieces of mat board create an elegant and dynamic composition that spirals outward towards the viewer. Untitled #1, one of Newton’s collagraphs, transforms carefully selected three-dimensional objects through the printing process while maintaining their unique textures and outlines.

“My concern as artist and individual is to be able to spark involvement and stimulate reaction. Because of an intense desire to communicate through plastic means, I have invented my own language, peculiar to itself. In doing so I turn away from obvious aspects of the external world and seek by various media to create my own world, one in which I may feel free to establish form and order as I choose.”6

Rachel Ciampoli

2023 Alfred Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellow, Delaware Art Museum

PhD candidate, Art History Department, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Join Rachel Ciampoli, PhD candidate in art history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and DelArt’s 2023 Alfred Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellow, for a special gallery talk. Rachel will discuss the works of art on view in The Artistic Legacy of James E. Newton: Poetic Roots, surveying the artist’s earliest experimentations, themes, and inspirations.

1. James E. Newton, “Development and Variations in Creative Aim and Means,” (master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1968), v.

2. Newton, “Development and Variations,” 2.

3. Newton, “MSS 0989: Oral history interview with James Newton, Part 1,” by Roger Horowitz, HIST 268 Oral History Interviews: African Americans and the University of Delaware Collection, University of Delaware Library, Newark, DE, October 11, 2021.

4. Newton, “MSS 0989: Oral history interview.”

5. James Newton: A Life Story in Art, directed by Sharon K. Baker (2016, Teleduction), vimeo.com/179488047.

6. Newton, “Development and Variations,” 1.

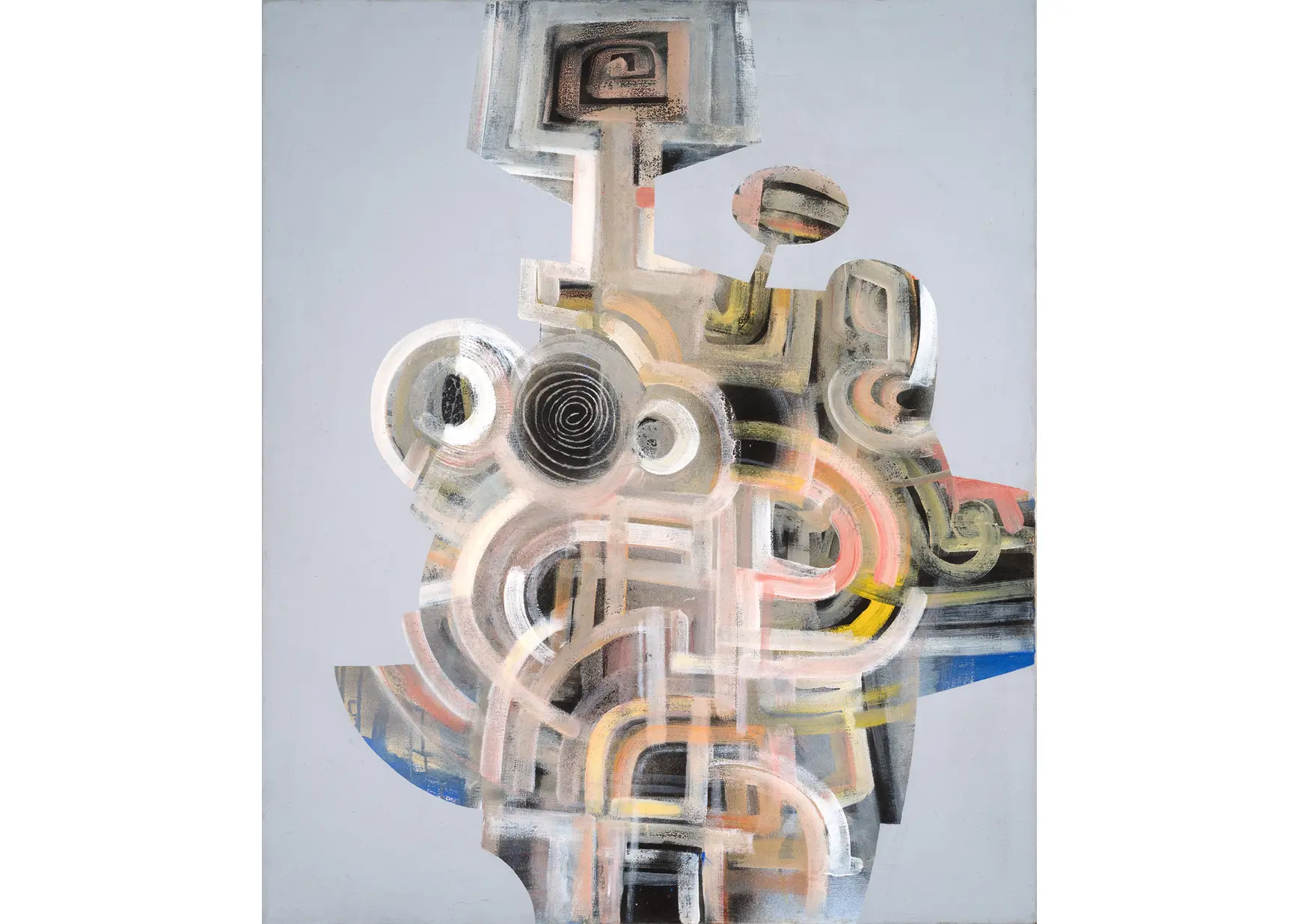

Top: The Love Machine, c. 1960. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Acrylic on canvas, 48 × 40 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.