In January 1894 author and artist George du Maurier took the world by storm with the first installment of his serialized novel, Trilby. The saga of the doomed artist’s model, which featured illustrations by du Maurier, appeared in eight installments in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, each issue selling out rapidly. In September 1894 Trilby was released in book form and by February 1895 had sold over 200,000 copies in the United States alone, making it one of the best-selling novels of the Victorian era.

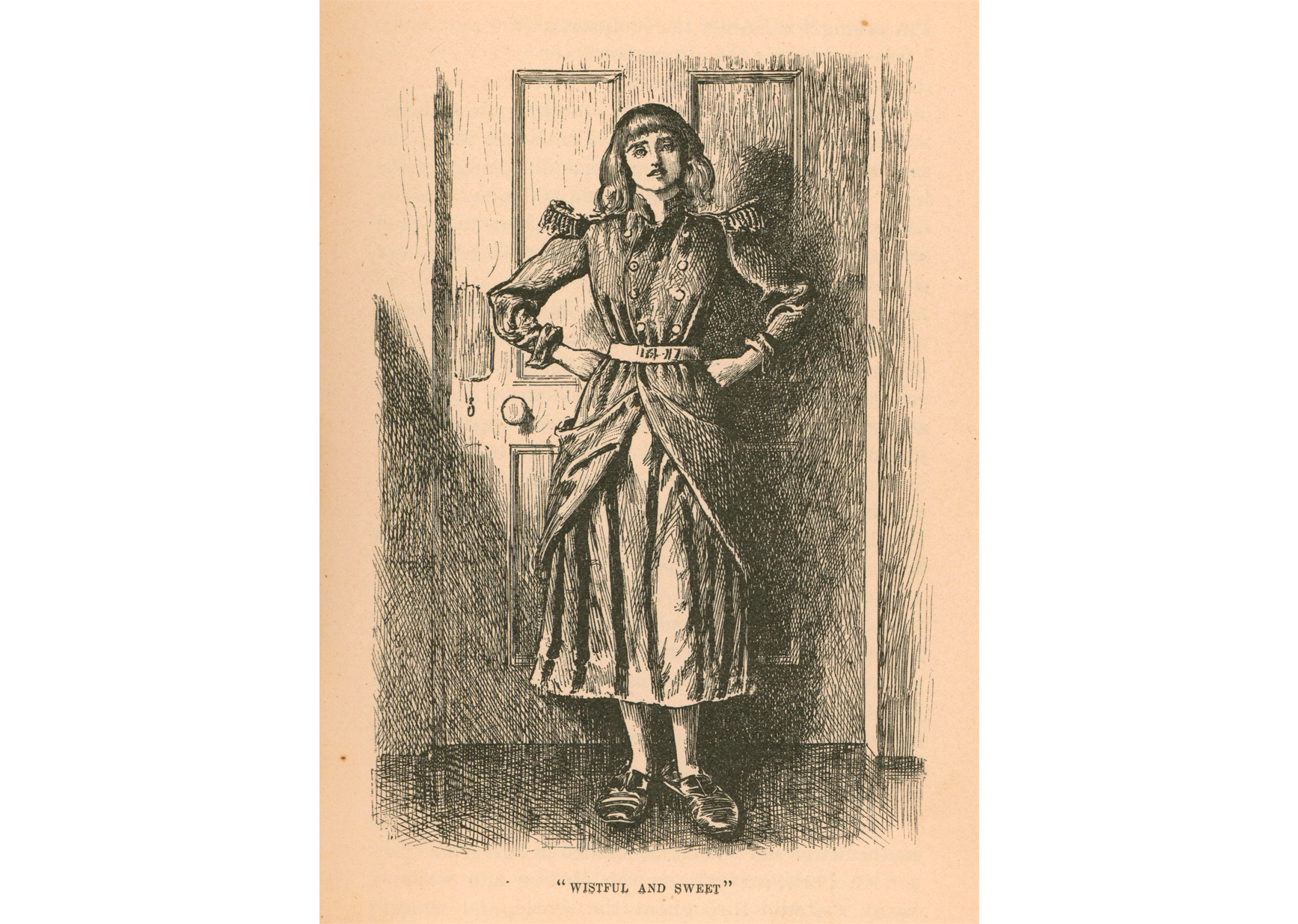

Set in the 1850s in bohemian Paris, the story follows the lives of the title character, an artist’s model said to have “the handsomest foot in Paris,” her love interest, artist Little Billee, and a musician named Svengali. Smitten by Trilby’s beauty and wanting to possess her, Svengali puts her under his spell with his powers of hypnotism, making the previously tone-deaf model an accomplished singer who performs all over the world in an amnesiac trance. Svengali keeps Trilby in this trance for five years, cutting her off from Little Billee, her true love, and ruining her health. Of course, this sensational tale has an equally melodramatic ending, with Svengali dying of a heart attack, Trilby dying of a nervous affliction, and Little Billee dying of a broken heart.

The popularity of Trilby is impossible to overstate. Author and poet Margaret Sangster acknowledged the profound effect it had on popular culture in her 1894 Harper’s Weekly article, “Trilby from a Woman’s Point of View”:

There are not a few people who will remember the first half of 1894, not for the hard times, nor for the strikes, nor the yacht-races, nor any other thing of public interest or private concern, so much as for the pleasure they had in reading Trilby. Never before did the month intervening between installments seem so long, nor did so many readers anxiously await the next development.

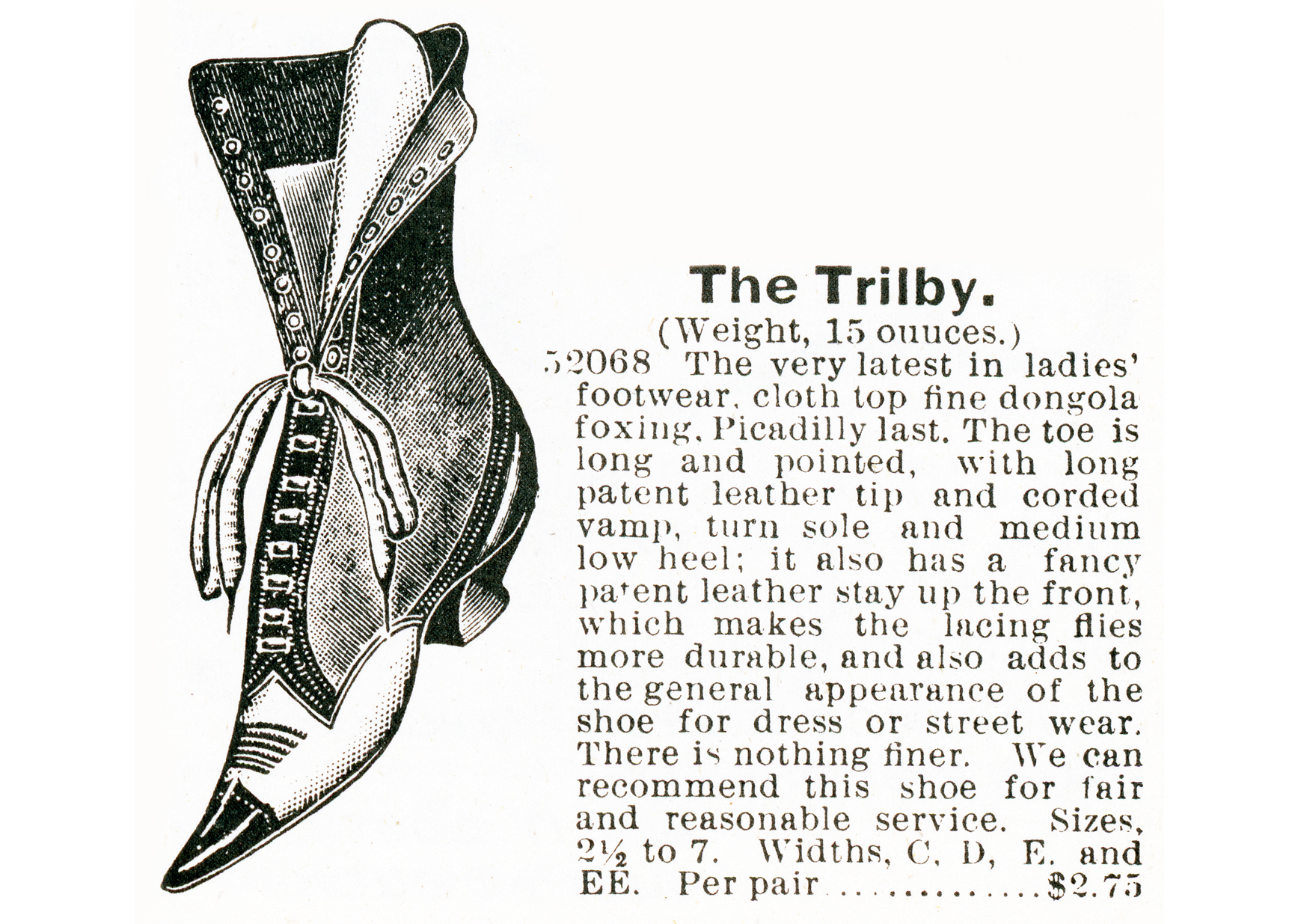

By the end of 1894 Trilby was a cultural phenomenon that had permeated nearly every facet of society, from fashion (Trilby-inspired shoes, hats, and—coinciding with another craze of the times—bicycling costumes) to housewares (foot-shaped toothpick holders and snuff boxes), to food (ice cream and even sausages in the shape of a foot).

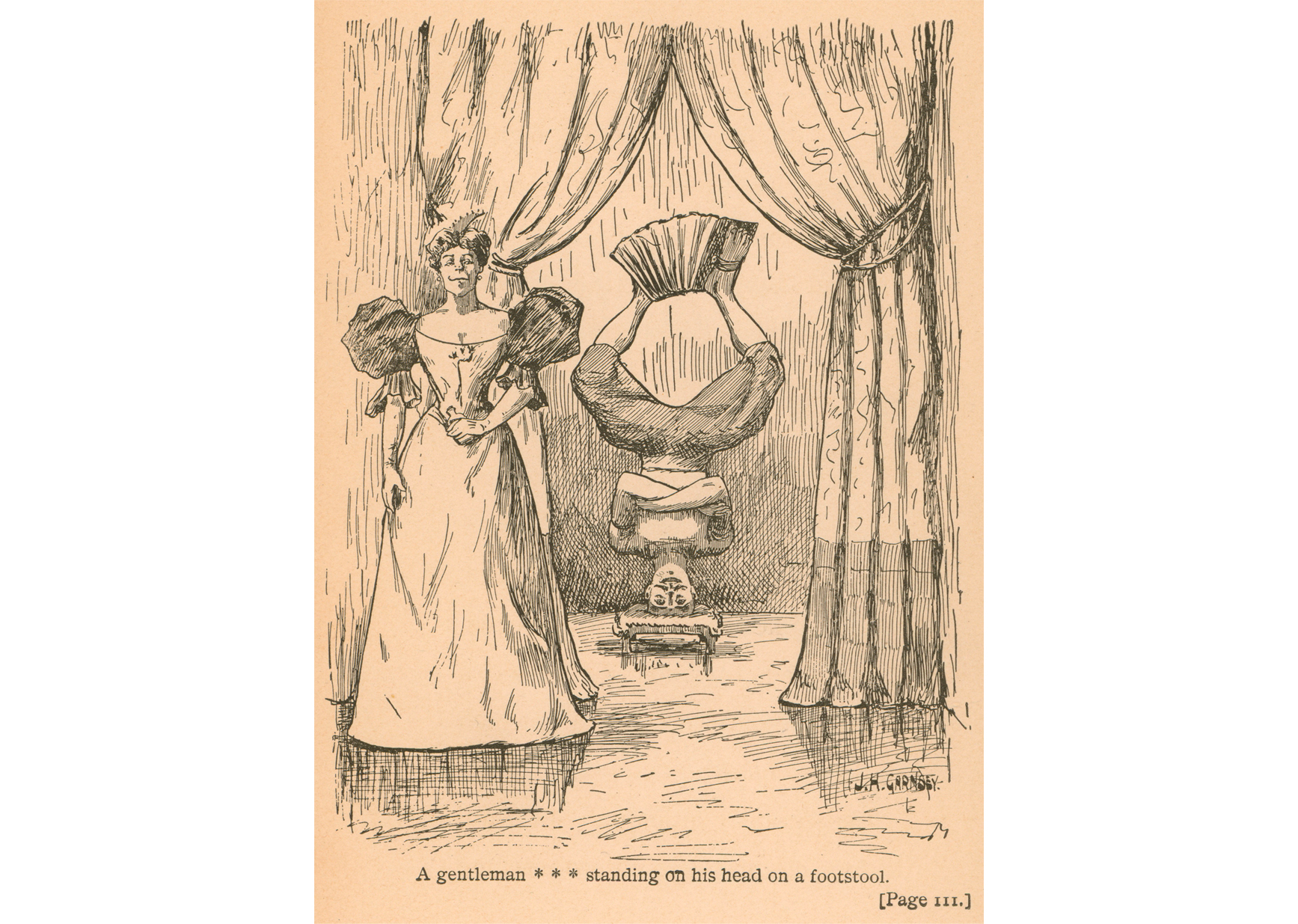

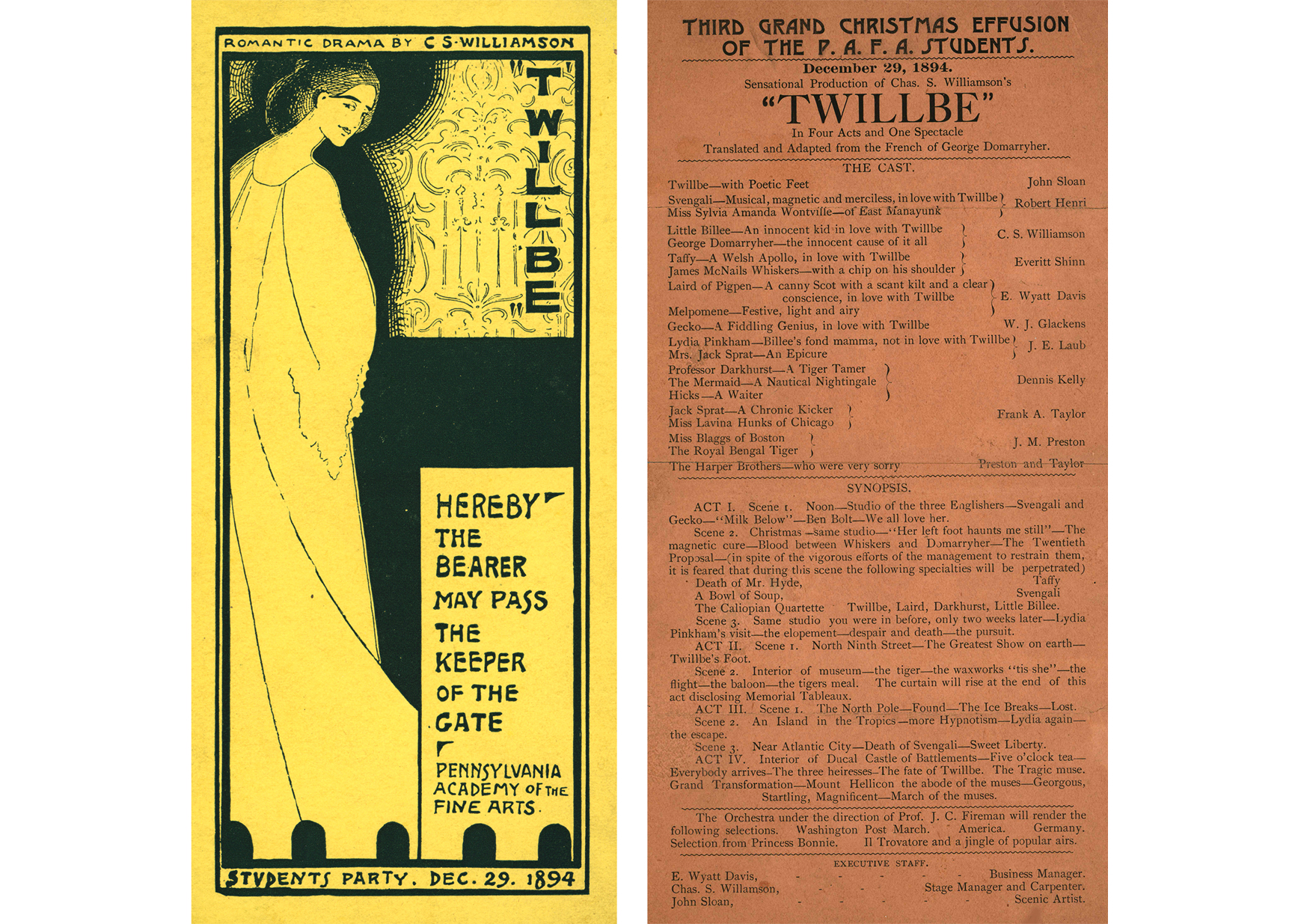

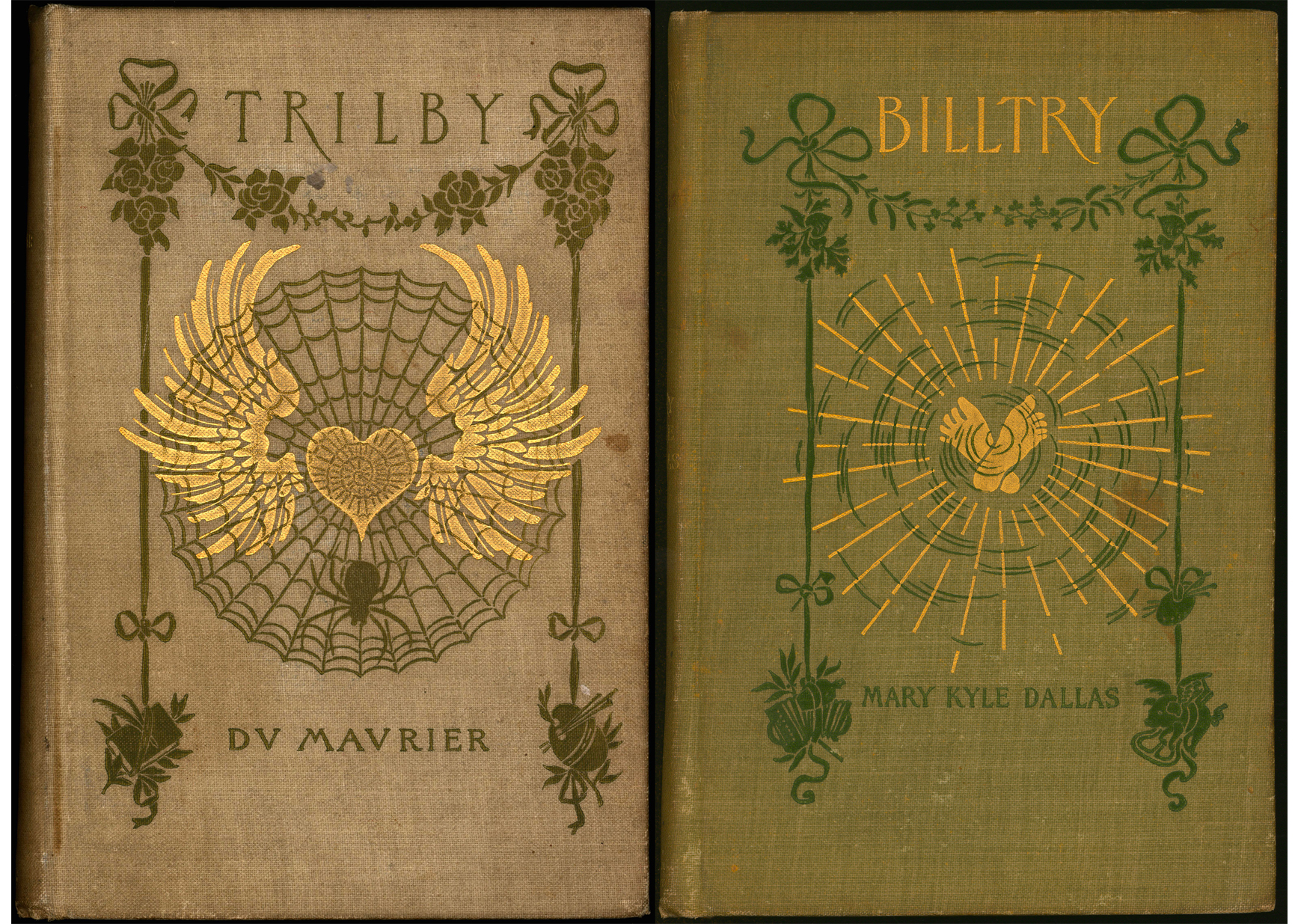

Of course, nothing this popular is safe from satire, and Trilby was no exception. The odd story of a woman’s beautiful feet inspired countless parodies, including an operatic burlesque called Thrilby: A Shocker in One Scene and Several Spasms, an amateur play by John Sloan and his friends called Twillbe, and a novel called Billtry, in which the title character is a male model with very long feet. Instead of becoming an accomplished singer, like Trilby, Billtry is taught to play the accordion with his feet while standing on his head by the evil Mrs. Snively.

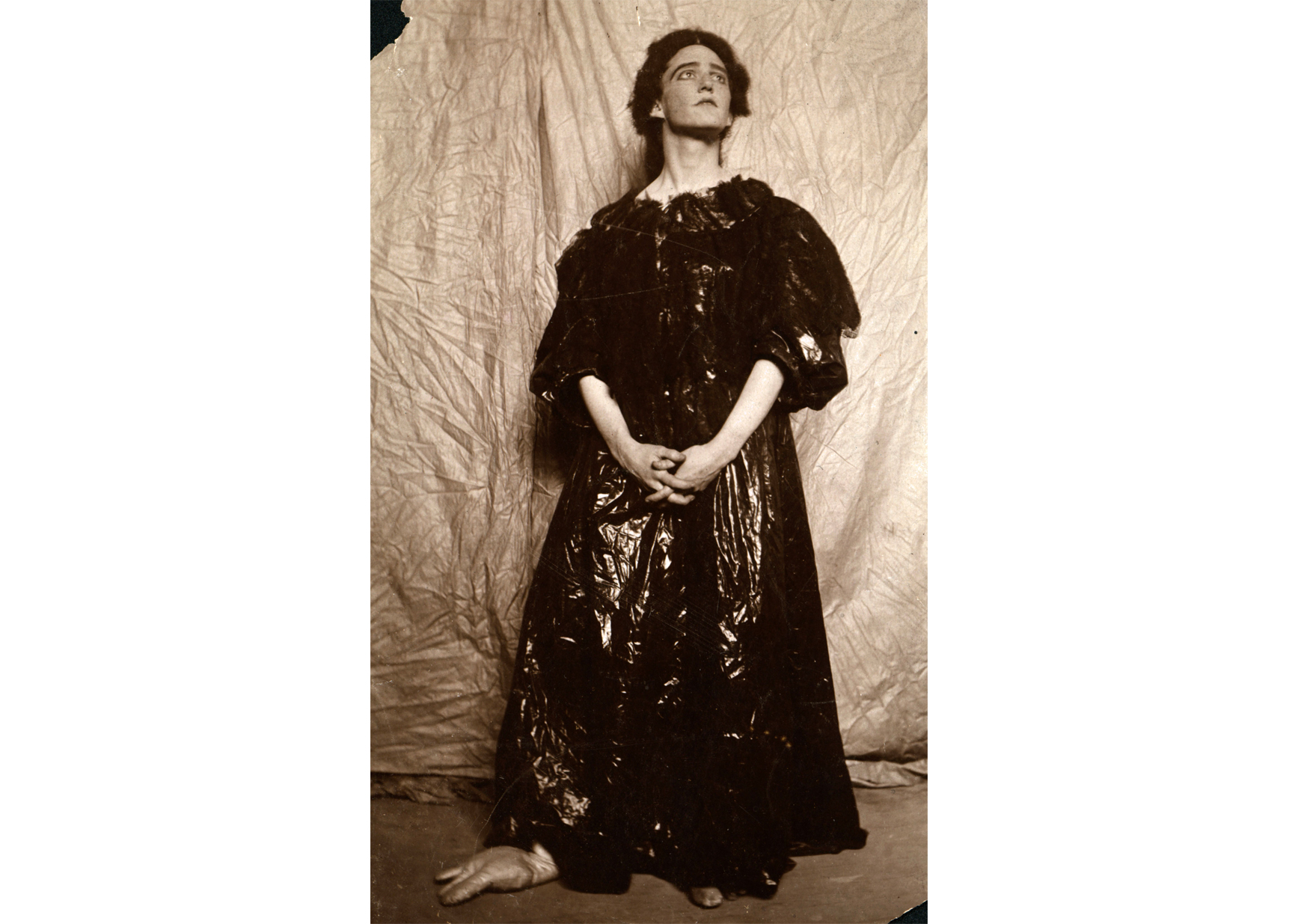

In the collections of the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives we find a few examples of these spoofs: the John Sloan Manuscript Collection contains photographs, a playbill, ticket, and script of Twillbe, performed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in December 1894 by Sloan (as Twillbe), Robert Henri (as Svengali), C. S. Williamson (as George Domarryher), and Everett Shinn (as James McNails Whiskers). Note Sloan’s enormous foot in the photograph!

We also have a copy of the novel Billtry, which is what I find the most exciting as the cover design itself is a parody of the original 1895 design for Trilby attributed to artist Margaret Armstrong. The Armstrong cover features references to the plot of the novel, including a book and quill, an artist’s palette, and a winged heart caught in a spider’s web, meant to symbolize Svengali’s ensnaring of Trilby and her inability to escape him. The parody cover, rendered by an unknown artist, looks very similar at first glance. Upon closer inspection, however, we see that an accordion and jug of wine have replaced the book and quill (a nod to Billtry’s ability to play the accordion with his feet), a pig with wings has replaced the palette (a reference to the phrase “when pigs fly,” meaning something that is impossible), and a pair of large feet have replaced the heart.

Though Trilby brought du Maurier fame and fortune, it also brought him an untimely death; some of his final words were reportedly, “Its popularity has killed me at last.” He died in October 1896, at the height of the Trilby boom and just after completing his last novel, The Martian, which began its first installment in Harper’s that very month. In a tribute to him, Willa Cather wryly noted that “Du Maurier certainly did his duty by his American publishers. They made a fortune on Trilby, and now to effectually advertise his new book he conveniently dies.” Trilby’s popularity waned significantly after du Maurier’s death, and most twenty-first-century readers have never even heard of it, though its influence on popular culture is still apparent today: it is often cited as the inspiration for Gaston Leroux’s 1910 novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (The Phantom of the Opera), and the term Svengali is still used to describe a person who manipulates and controls with evil intent.

A virtual exhibition, featuring more Trilby-inspired items from the Museum’s collections, may be found on the DelArt website, and several items are on view through November in the cases outside the Library on the lower level of the Museum.