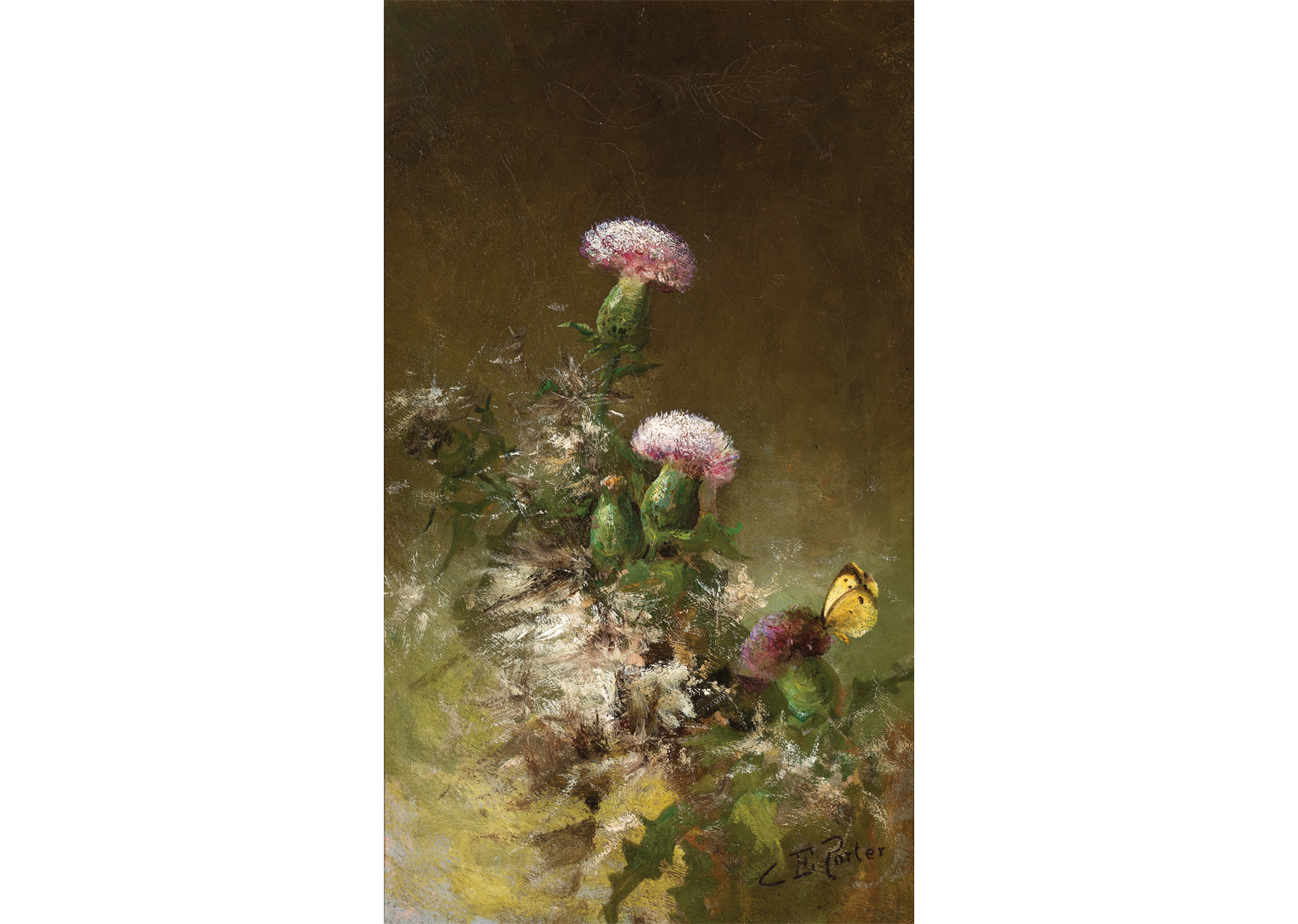

It’s been just under a year since the Museum purchased Charles Ethan Porter’s Thistles with Butterfly, which is now on view in Gallery 5, a space dedicated to American art from the middle of the 19th century. Featuring a Clouded Sulphur butterfly alighting on a thistle head, this lovely canvas demonstrates the artist’s interest in his local landscape. Although Porter developed his approach to painting flowers in Paris, his family’s garden in Connecticut provided inspiration for much of his career. In the 1880s, when he painted this, appreciation was increasing among gardeners and artists for wildflowers and the insects that visit them. Enthusiasm was also growing for looser, more expressive brushwork and for outdoor painting—Thistles with Butterfly practically vibrates with the vitality of nature. Adding to the floral energy, the frame is decorated with twining grape vines. (With a label from J. H. Eckhardt in Hartford, the frame is very likely original to the painting.) We were delighted to add Thistles with Butterfly to the Museum’s collection in 2023. DelArt had no significant floral paintings from the 19th century, and this one—with its Parisian flair and attention to native plants—has a lot to say about the period.

This acquisition is also significant because Porter is one of a small number of African American artists, alongside Robert Duncanson and Edward Bannister, to build painting careers in the 19th century. Over the past five years, the Museum has acquired works by each of these three artists, allowing us to tell a more inclusive story of American art. Thistles and Butterfly is the first work by Porter to enter the collection. As we look toward our 2024 exhibitions The Artistic Legacy of James E. Newton: Poetic Roots and There is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art, deepening our 19th-century collection provides context and helps make possible programs like The ABCs of Black Art History, which launches this year.

About Charles Ethan Porter and Thistles and Butterfly

Raised in Rockville, Connecticut, Porter suffered poverty and loss as a youth. Two of his brothers fought in African American regiments of the Union Army during the Civil War, and one died fighting in Virginia. Seven of his siblings died young of illnesses. After high school, Porter studied painting at Wesleyan Academy before he was accepted at one of the nation’s leading art schools, the National Academy of Design in New York, where he studied from 1869 to 1873. Porter lived in New York and spent summers in Rockville until late in 1877, when he set up a studio in Hartford, Connecticut. The city had a vibrant artistic scene at the time, with wealthy collectors and resident artists including Frederic Edwin Church. Porter’s still-life paintings attracted notice in the local papers. He was working in a meticulously detailed, trompe l’oeil manner, depicting flowers or fruits, sometimes visited by equally realistic insects. His still-life groupings were simply composed—often featuring a single type of fruit or flower—and free of fancy vases or exotic plants.

A studio sale of Porter’s paintings in 1881 earned him about $1,000 to travel to Paris, where he enrolled at the École Nationale Supériere des Arts Décoratifs and the Académie Julian. In the summer of 1882, Porter traveled to Fleury, close to Barbizon, where he painted landscapes, but his fruit and flower pictures were the works most admired in France, as they had been in the U.S. In Paris, Porter lived down the street from one of the leading French still-life painters, Henri Fantin-Latour, and first-hand exposure to the French artist’s paintings probably encouraged Porter to work in a looser, more painterly style.

Early in 1884 Porter was back in Hartford. The local press supported his work, praising it as even better now that he incorporated “the mode of treatment which is so characteristic of French art today.” His “broader, freer style” was contrasted favorably to his earlier “dainty, almost finicky” work, yet he had trouble selling enough work to support himself in Hartford and moved between New York and his family home for several years, before settling permanently in Rockville around 1900. He exhibited in all three cities and in Springfield, Massachusetts.

With its expressive brushwork, Thistles with Butterfly reflects Porter’s post-Paris style as well as his abiding interest in flowers and insects. Porter is best known for tabletop still life pictures of flowers in vases, but he also produced landscape pictures. Focused on a local plant in nature, Thistles with Butterfly bridges the genres of landscape and floral still life. The simple brown background keeps attention on the colorful subjects and is typical of the artist’s still-life compositions.

Considered both a flower and weed, the thistle is an evocative subject. In the mid-19th century, thistles often appeared in religious paintings, evoking the suffering of Jesus. Its spiny leaves are associated with pain and protection, and its ability to thrive in inhospitable places links the plant to resilience. The plant’s rich symbolism resonates with the artist’s experiences.

Porter’s network included local white artists as well as his extended family, but he struggled to make a living as a painter in a small community—a struggle made much more challenging for Porter as a Black artist. Porter exhibited and sold regularly, as well as teaching, through the early 20th century, and he seems to have been quite prolific—news reports indicate him selling hundreds of works at a time in studio sales—but his difficulties are also clear.

Heather Campbell Coyle

Curator of American Art

To learn about Porter, see Charles Ethan Porter: African-American Master of Still Life (New Britain Museum of American Art, 2007)

Thistles with Butterfly, c.1888. Charles Ethan Porter (1847–1923). Oil on canvas, 20 3/16 x 12 1/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2023.