Thomas Nast (1840-1902), the famed nineteenth-century political cartoonist, is largely responsible for shaping the modern American image of Santa Claus. Born in Germany, Nast immigrated to the United States with his mother and sister in 1846. He studied at the National Academy of Design before beginning his professional career at Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1855. His talent for visual storytelling soon caught wider attention, and in 1862 he joined the staff of Harper’s Weekly, where he became nationally known for his scenes of the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln once referred to Nast as “our best recruiting sergeant” for the Union, praising the power of his stirring and heroic depictions of wartime events. A staunch supporter of the Union with strong abolitionist convictions, Nast frequently infused his drawings with his political beliefs.

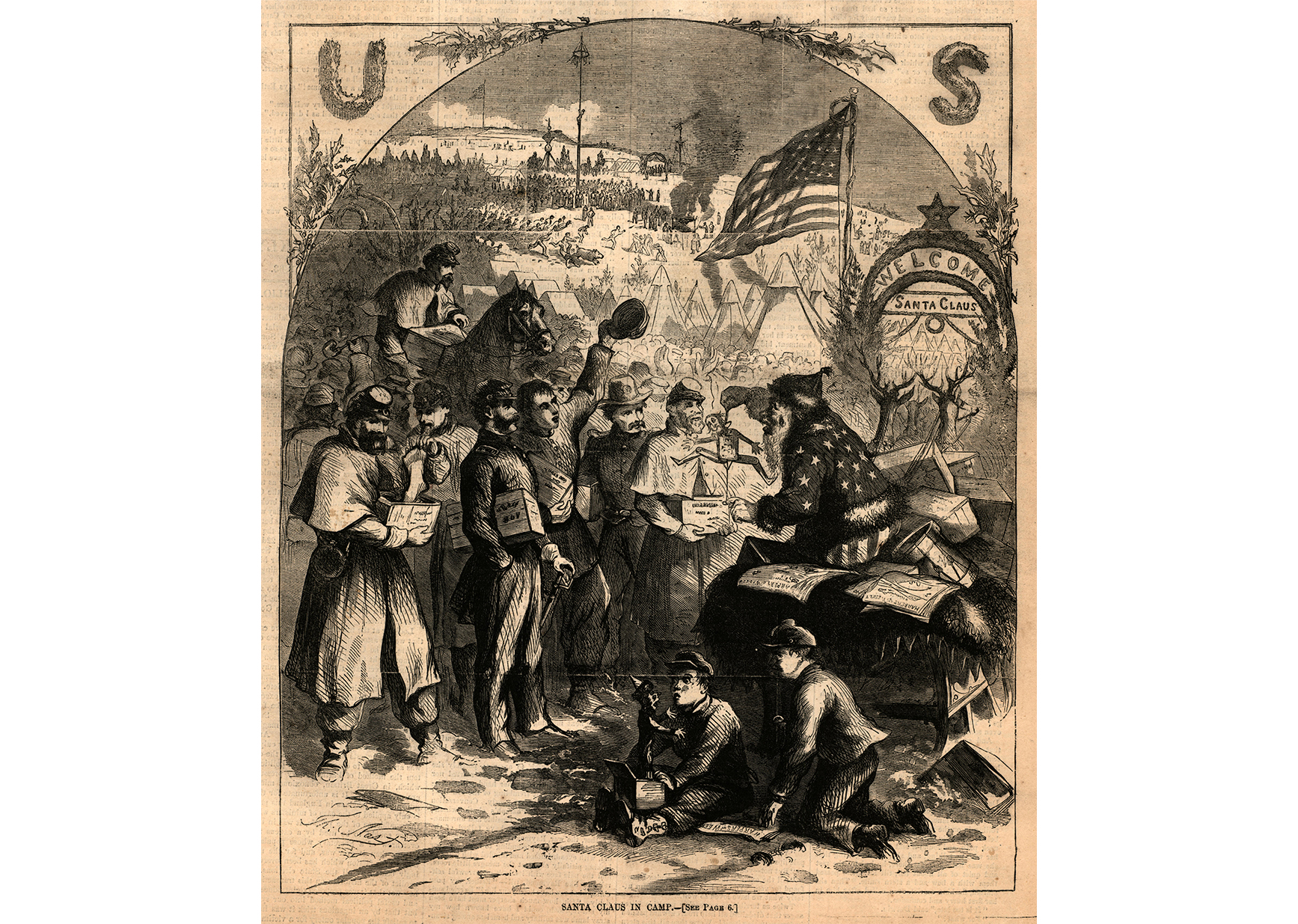

Nast’s first depiction of Santa Claus appeared in the January 3, 1863 Christmas issue of Harper’s Weekly, in an illustration titled “Santa Claus in Camp.” In this image, Santa visits a Union encampment, distributing gifts to soldiers. Most notably, Nast dressed Santa in a coat patterned with stars and trousers striped like the American flag. Santa holds a puppet labeled “Jeff,” a not-so-subtle swipe at Confederate president Jefferson Davis. The message was unmistakable: even Santa supported the Union cause.

Over the years, Nast continued to refine and elaborate Santa’s image. His illustrations provided the first known references to Santa living at the North Pole and maintaining a toy workshop—details that soon became fixtures of the Santa Claus mythology. Between 1863 and 1886, he produced 33 Christmas-themed images for Harper’s Weekly, all but one featuring Santa himself.

Perhaps Nast’s most iconic rendering of Santa Claus is his 1881 illustration “Merry Old Santa Claus.” This version reflects the artist’s continued engagement with national issues. Santa appears with a soldier’s backpack, a dress sword, and a U.S. belt buckle—symbols of military readiness. A pocket watch in Santa’s hand alluded to a then-ongoing congressional debate over pay for sailors and soldiers, reminding lawmakers that time was running out to make their decision. Nast’s Santa, even in peacetime, remained linked to civic responsibility and national identity.

Merry Old Santa Claus, from Harper’s Weekly, January 1, 1881. Thomas Nast (1840-1902). Printed matter. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

Merry Old Santa Claus, from Harper’s Weekly, January 1, 1881. Thomas Nast (1840-1902). Printed matter. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

The influence of Nast’s imagery extended far beyond the pages of Harper’s Weekly. Before the Civil War, Christmas was officially recognized as a holiday in only 18 states. But in the postwar years, as Americans sought to heal from a long and bitter conflict, Nast’s warm, approachable, and distinctly American Santa offered a comforting point of unity. At the same time, rapid industrialization encouraged new patterns of consumption, and the celebration of Christmas quickly intertwined with the growing culture of gift-giving. Nast’s visual invention of Santa Claus, arriving at just the right moment, helped ignite the nationwide embrace of Christmas as a major domestic and commercial holiday.

Join us for Treasures of the Season: Holiday Gems from the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives on Friday, December 5 at the Delaware Art Museum, or Thursday, December 11 at the Lewes Library. We’ll explore the history of Christmas traditions and showcase several of Thomas Nast’s iconic Santa Claus illustrations, including the newly acquired and exceptionally rare Harper’s Weekly issue featuring “Santa Claus in Camp.” Plenty of other festive surprises will be on hand as well.

Written by Rachael DiEleuterio, Librarian and Archivist

Written by Rachael DiEleuterio, Librarian and Archivist

Top: Santa Claus in Camp, from Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863. Thomas Nast (1840-1902). Printed matter. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.