How the West is One

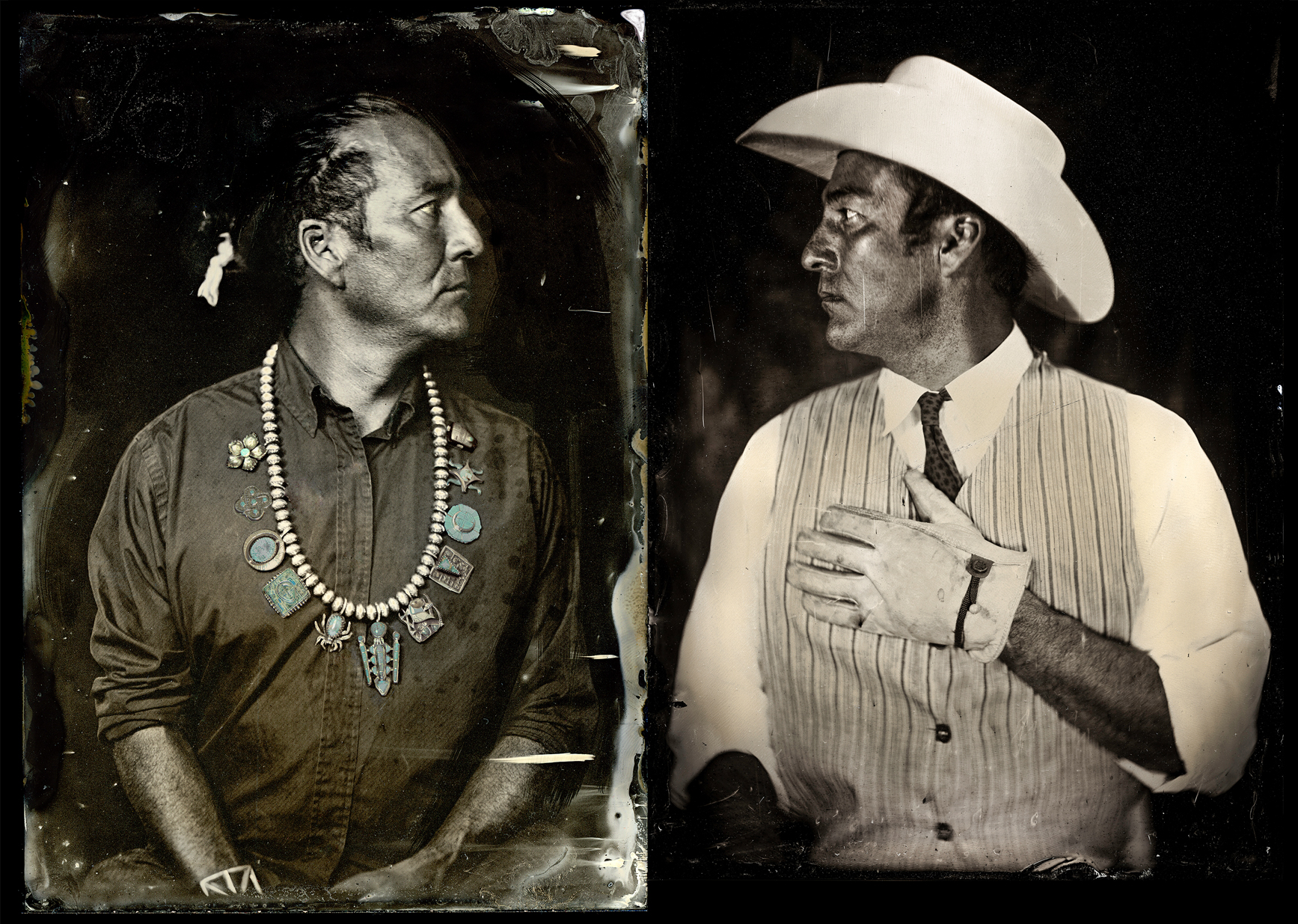

In the photograph How the West is One, two men look towards one another in a standoff. The figure on the left wears a collared shirt, a cuff, and an intricate metal necklace holding eleven pendants. His hair is tied in a tsiiyéél, indicating wisdom and disciplined thought in Diné/Navajo culture. On the right, the second figure appears dressed in a white collared shirt, pinstripe vest, tie, and a leather work glove on his raised hand. A wide-brimmed cowboy hat sits on his head. Though their attire sets them apart, the men’s faces reflect one another in profile as they intently gaze towards the other.

The two figures in How the West is One are duplicates played by the artist Will Wilson. In this double self-portrait, Wilson depicts himself as the quintessential late nineteenth-century character types of the “Cowboy” and “Indian” together in one picture frame. Each is generalized as a trope but seen through Wilson’s unique lens. The figures recall the popular children’s game “Cowboy and Indians,” which pits these two groups against one another in the struggles over the American West. They are often set up in old Western movies and books as diametrically opposed. In How the West is One, however—the “Cowboy” and “Indian” are both distinct and the same. Wilson plays on simplified and outdated narratives of identity in his photograph, highlighting the ways that photographs are deeply complex spaces of self-definition.

Will Wilson’s Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange

Will Wilson (b. 1969) is a contemporary Diné/Navajo artist and citizen of the Navajo Nation living and working in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The work shown in this summer’s exhibition at DelArt, In Conversation: Will Wilson, represents an overview of a series known as the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX). Begun in 2012, CIPX is a series of portraits made through the wet collodion photographic process, similar to the one the early twentieth-century photographer Edward S. Curtis was well-known for using in his The North American Indian project (1907-1930). In this process photographic negatives are printed with light-sensitive chemicals on a metal or glass surface, often referred to colloquially as a “tintype.” Wet collodion photography became massively popular for portraiture in the latter nineteenth century due to its high level of detail, reproducibility, durability, and relative cost-effectiveness.

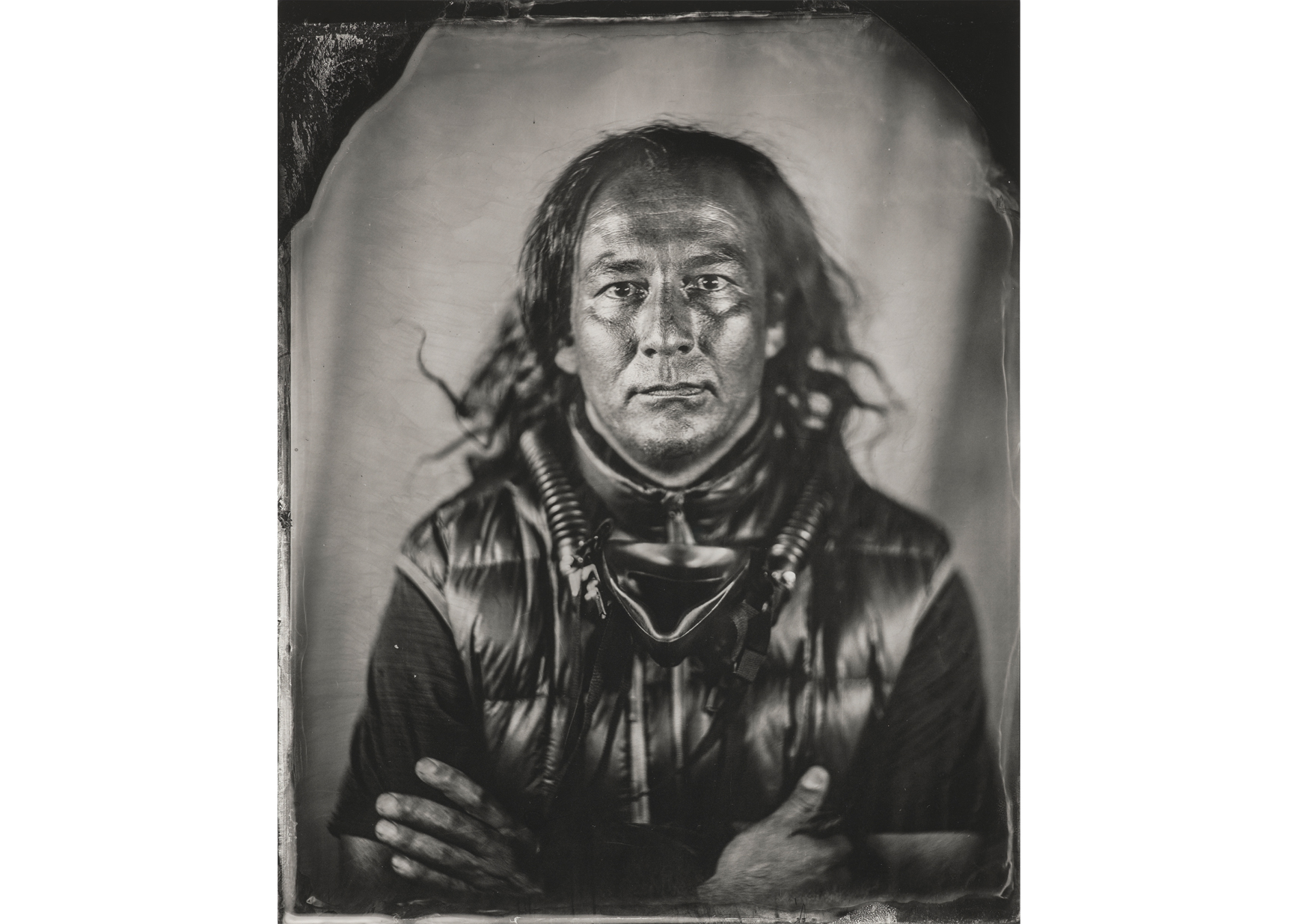

Will Wilson (b. 1969), Will Wilson, Citizen of the Navajo Nation, Trans-customary Diné Artist, 2013, printed 2018, archival pigment print from wet plate collodion scan, 22 x 17 in. Art Bridges. Photography by Brad Flowers.

For Wilson, developing photographs of Native peoples through this process puts him in direct conversation with Curtis and other photographers of his time who turned their cameras towards representing Indigenous peoples, often depicting them incorrectly as vanishing representations of the past. Curtis was famous for post-production editing of his photographs through dodging, burning, cropping, and retouching elements (manual processes that can now be done in Photoshop) to make them appear more nostalgic. Wilson’s project considers Curtis’s impact while wholly rejecting his conclusions. In Wilson’s images, sitters are living, breathing, and thriving. Wilson’s hope for the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) is that he can “indigenize the photographic exchange,” through collaboration and exchange that can then “form the basis for a re-imagined vision of who we are as Native people.”

Wilson held the first series of Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) photoshoots at the 2012 Santa Fe Indian Market in New Mexico. He invited friends, students, and colleagues to be subjects, thus beginning the project that is now in its tenth year. Wilson engages his sitters in a direct process of reciprocity, wherein he gifts them with the resulting 8×10 tintype plate after taking a high-resolution scan for his archive. These scans are then titled with the person’s name and a designation for the site the photograph was taken at, making them traceable to their source. Each subject is encouraged to come to their session in whatever clothing and objects are significant to them. Through the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX), Wilson has created a counter-archive of nearly 4,000 photographs that feature both Native and non-Native subjects from across the globe. The series has become a central part of the artist’s practice, and he has been sponsored by institutions worldwide to host photoshoots highlighting contemporary Indigenous communities.

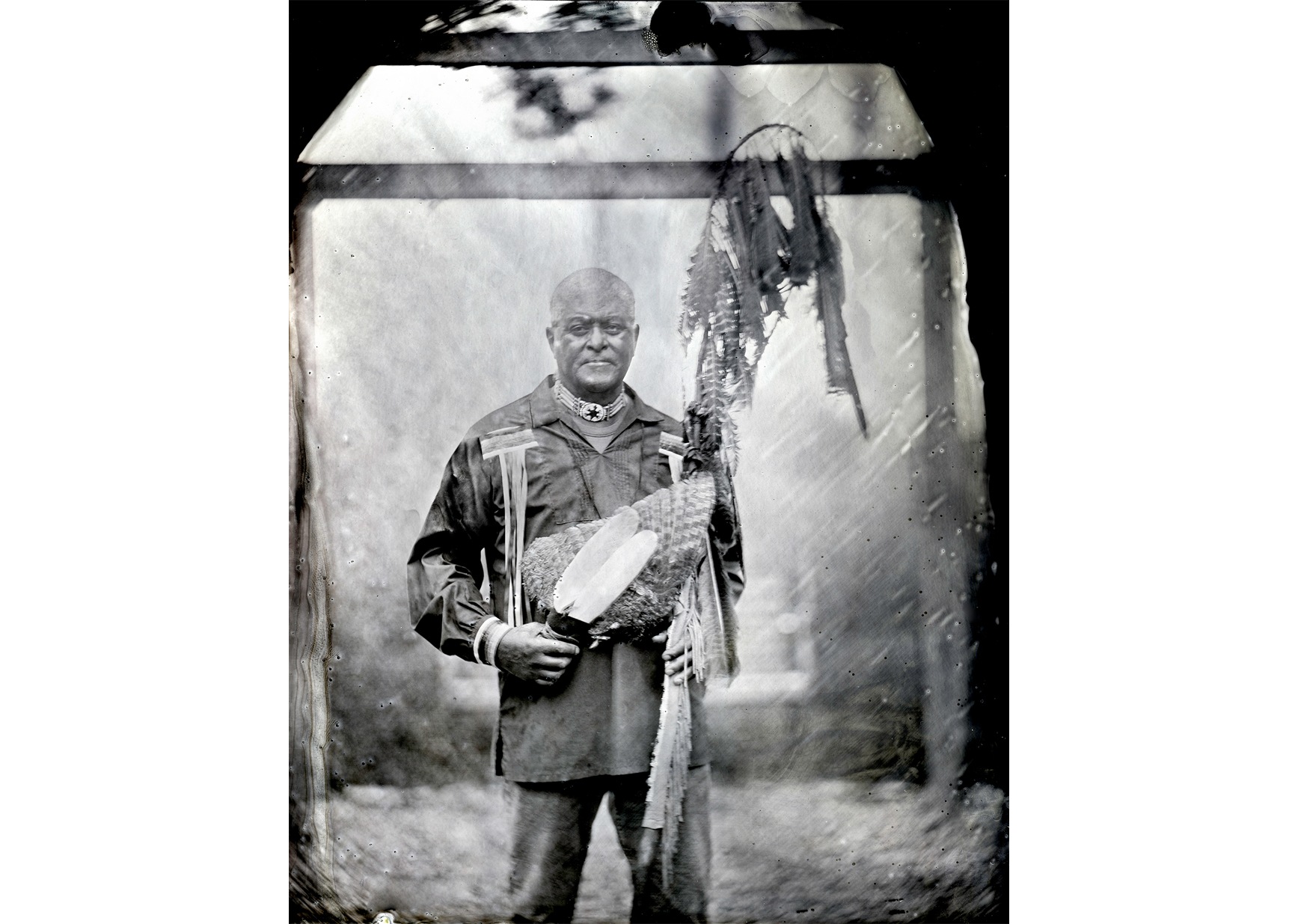

Will Wilson (born 1969). Principal Chief Dennis Coker, Citizen of the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware, 2022. Archival pigment print from wet plate collodion scan, image: 40 × 31 1/4 inches. Artwork © Will Wilson Art & Photo, LLC.

CIPX in Delaware

In May 2022, Wilson’s CIPX series was brought to Delaware when citizens of the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware (The Original People) and the Nanticoke Indian Tribe (The Tidewater People) were invited to sit for their own CIPX portraits. Working with Principle Chief Dennis J. Coker (Lenape) and Chief Natosha Carmine (Nanticoke), the Delaware Art Museum facilitated a day-long photoshoot that featured individuals, families, and objects/images of personal significance. Many shared stories of what and who they brought with them, which will be exhibited alongside the final photographs. These personal narratives are powerful examples of fortitude, family, and cultural continuity within these communities.

Finally, Wilson pushes the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) project into the contemporary with the inclusion of “Talking Tintypes,” which use Augmented Reality (AR) technology to bring the images to life. You can download the free app in the App Store and/or Google Play, and scan select exhibition images to access interactive AR content. Across this survey of ten years of work, Wilson’s still and moving images make clear that Indigenous peoples persist and continue to reclaim the camera as a meaningful mode of self-representation. In Conversation: Will Wilson is a powerful testament to such work and the important conversations it propagates.

Kaila T. Schedeen

PhD Candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, Guest Curator

In Conversation: Will Wilson is on view at the Delaware Art Museum July 9 – September 11, 2022.

The Delaware Art Museum acknowledges with respect that the Delaware Art Museum and its grounds stand on Lenape land. The Lenni Lenape (The Original People) have lived in our region for thousands of years. Many were forced to migrate west and north where their descendants live today, but some never left, and some returned.

The region we now call Delaware is home to the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware, the Nanticoke Indian Tribe (The Tidewater People), and diverse Indigenous peoples today. We pay respect to their Elders, past and present. We honor the animals, plants, and waters of Lenapehoking—the traditional Homeland of the Lenape people within which we stand.

We invite you to join us in acknowledging the sacredness of this place, honoring its original and living stewards, and offering respect and care for the land and its resources.

We also acknowledge the land, elements, and beings of Oga Po’geh (“White Shell Water Place,” known today as Santa Fe, New Mexico) and Dinétah (“Among the People,” the ancestral homelands of the Diné), where the Diné (Navajo) artist Will Wilson lives and creates much of his work. We honor these places and their Indigenous peoples from the past, present, and future.

Top image: Will Wilson (born 1969). How the West is One, 2014, printed 2016. Archival pigment print from wet plate collodion scan, 24 × 36 inches. Collection of the artist.

In Conversation: Will Wilson is organized by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, with generous support provided by Art Bridges. This exhibition and its related programming are sponsored by M&T Bank. This exhibition is made possible in Delaware by the Emily du Pont Exhibition Fund. Additional support was provided, in part, by a grant from the Delaware Division of the Arts, a state agency, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts. The Division promotes Delaware arts events on www.DelawareScene.com.