Excerpted from Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks (Wilmington, DE: Delaware Art Museum, 2021).

Though Percy Eugene Ricks, Jr. began what would be a long career in arts and education in Wilmington in 1947, the roots of what would become Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc. took hold in the mid-1960s. It was in 1964 that Ricks began teaching at P. S. DuPont High School as the art and humanities instructor. Four years later, he was still there during the uprising that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and National Guard occupation of Wilmington. By creating Aesthetics Dynamics and curating Afro-American Images 1971, Ricks nurtured a group of Wilmington’s dedicated arts and culture professionals. In doing so, he created an innovative model that addressed the needs of the African American and artistic community in the city circa 1970.

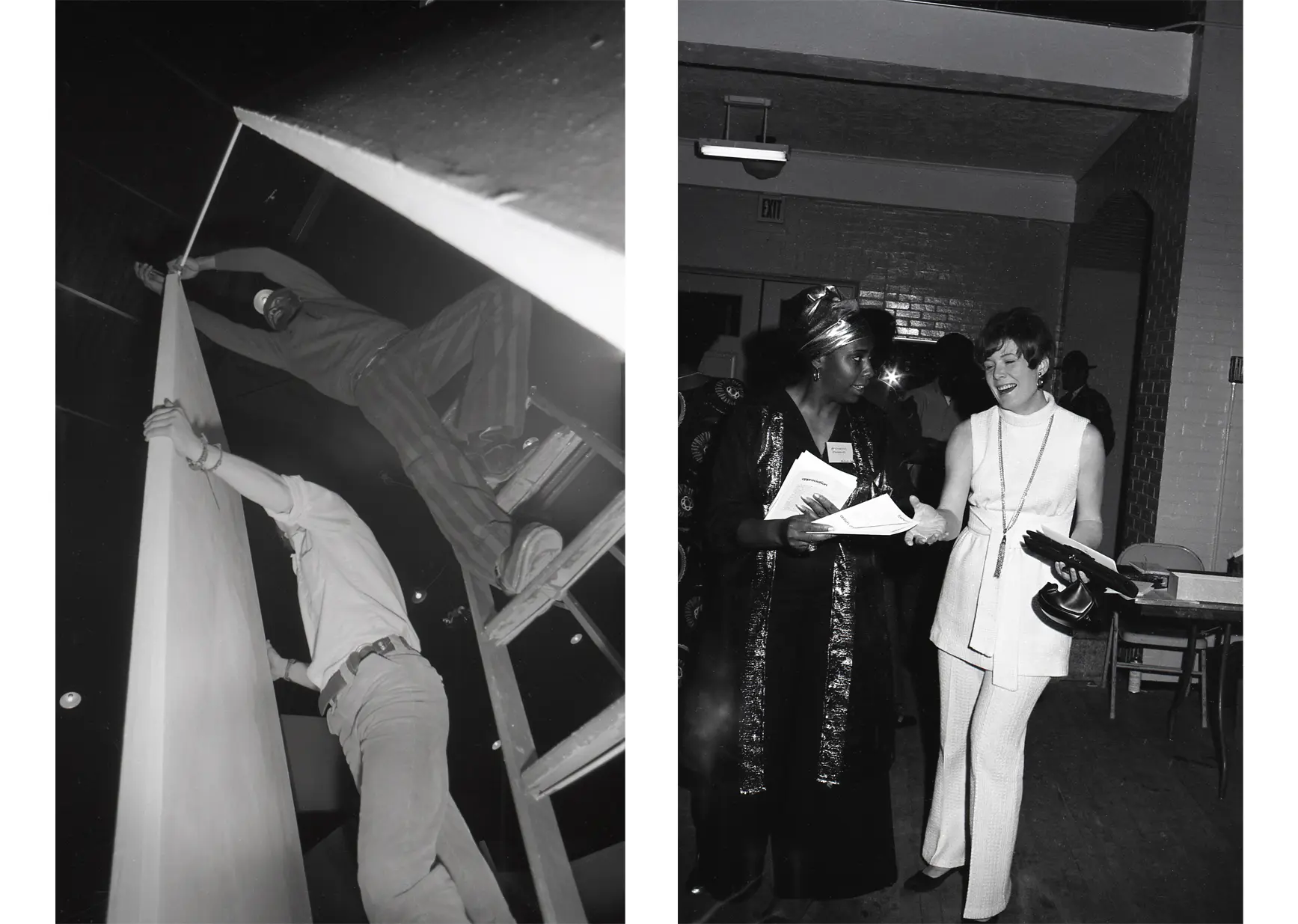

Left to right: Photograph of Simmie Knox (center) during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). | Photograph of Gertrude Redden Jenkins (left) and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Left to right: Photograph of Simmie Knox (center) during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). | Photograph of Gertrude Redden Jenkins (left) and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Ricks’ first position in Wilmington was as an art teacher at the Absalom Jones School in 1947, and in October 1948 he was employed as the first full-time African American art instructor in the city’s school district. Ricks quickly immersed himself in the cultural fabric of the city and began to establish the networks that would later support Aesthetic Dynamics’s membership. He exhibited his work with Edward Loper Sr. and served on the planning committee for the development of F. D. Stubbs Elementary School, where he would later teach. Ricks also became active in the Delaware Fine Arts Council, serving as chairman in 1959. Education was at the core of his work. He chaired the planning committee for Stubbs Day (established in 1960 to celebrate the life of Dr. Frederick Douglass Stubbs, the elementary school’s namesake). In 1961, he was a member of Studio Ten. Other members included Robert C. Moore, Theodore Wells I, Gertrude Jenkins, Marilyn Rittenhouse, Muriel Cooper, Marie Goss, and C. Charles Carmichael. Such were Ricks’s networks when he started at P. S. DuPont High School in 1964.

Photograph of Carol Shrier Reed during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of Carol Shrier Reed during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

In 1968, in addition to teaching, Ricks was in a critical position as program consultant for the Greater Wilmington Development Council. He shared with his mentor, James A. Porter, that plans had begun as early as 1965 to shift the focus of the then Christina Community Center of Old Swedes from recreational programming toward what Ricks saw as a dire need: integrated support of the visual and performing arts for greater New Castle County. Informed by more than 20 years’ work in arts and education in Wilmington, and a summer 1968 feasibility study, Ricks embarked on a holistic development and evaluation process to establish a program that would meet the needs of all ages in personal and cultural growth. His “Wilmington Visual and Performing Arts Center” model addressed new media (television), African American history, theater workshops, and gallery space, for example. Ricks believed that by nurturing first the “various ethnic groups in the immediate community which have made cultural contributions to our society” and then expanding “to encompass a knowledge of worldwide ethnic groups and their contributions to the society of man,” the entirety of Wilmington’s social and cultural life would be enhanced.[1] As Ricks continued to develop and expand the description of the Christina Cultural Arts Center’s programming, he specified emotional, intellectual, aesthetic, perceptual, physical, and social growth as objectives.

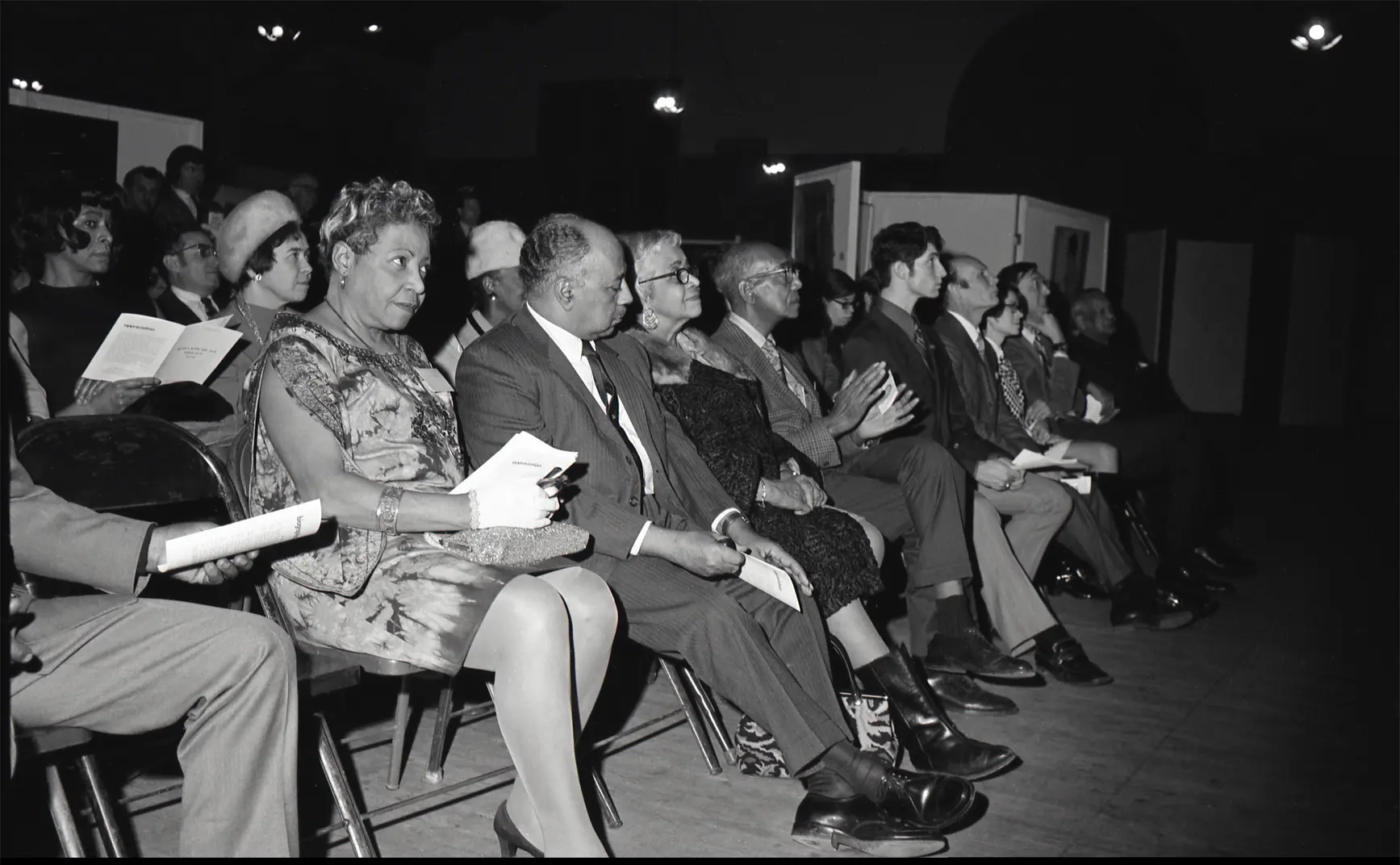

Photograph of (left to right) Delilah W. Pierce, Alma Thomas, and Dorothy Porter with Larry Erskine Thomas’ Africa—The Source during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of (left to right) Delilah W. Pierce, Alma Thomas, and Dorothy Porter with Larry Erskine Thomas’ Africa—The Source during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

To begin to understand Ricks’s goals for the 1971 exhibition, it is useful to examine his motivations in establishing an entity with the tagline, “creative use of the arts and sciences for humanity.” Numerous factors likely led to the founding of Aesthetic Dynamics and its ambitious first project, but the 1968 occupation of Wilmington was a probable key local influence. The city’s residents joined in the national mourning of the loss of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. When the community’s response escalated, the National Guard was activated, and remained in the city for nine months, constituting the longest occupation of a U.S. city following King’s murder. Tensions from the prolonged military presence, coupled with the flight of many downtown residents to the suburbs, created for some a culture of fear and uncertainty about venturing into the city. Such anxieties were mitigated through various solutions initiated by government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private individuals, such as Ricks.

With the traumatic events of 1968 still fresh, Ricks and the group of dedicated arts professionals established Aesthetic Dynamics and conceptualized a major exhibition to connect the local community with the contemporary contributions of Black artists. Of equal significance for Ricks was a means to publicly recognize and celebrate several distinguished individuals in the field. The exhibition was dedicated to his mentor James Porter, who had passed away on February 28, 1970. Romare Bearden, Loïs Mailou Jones, and Hale Woodruff each received an honorarium for their contributions to the arts and humanities at the February 5 opening events.

Photograph of Dr. Albert J. Carter and guest with James A. Porter’s Self-Portrait (1957), Shattered Mirror (1955), and Spanish Man with Ribbon (date unknown) during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of Dr. Albert J. Carter and guest with James A. Porter’s Self-Portrait (1957), Shattered Mirror (1955), and Spanish Man with Ribbon (date unknown) during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Descriptions of Afro-American Images 1971 and its objectives from the time vary. The newly founded Delaware State Arts Council was the lead sponsor, and council coordinator Polly Buck announced it as the first original exhibition of art by African Americans in the state. The Wilmington Armory (where the guard was housed during the 1968 occupation) hosted the exhibition, and while rentals were common, the art exhibition, which the writer compared to the 1913 New York Armory show, was a first. The space was selected for its size, location, and status as a community space, with Ricks noting that, “The armory is a place where you can walk in regardless of how you are dressed, unlike a museum.”[2] Afro-American Images 1971 represented the creation of a space for Black artists who were largely excluded from major arts institutions and an experience for Black museumgoers who, in 1971, were likely still experiencing de factor segregation in many parts of the United States, Wilmington included.

Listed on the exhibition pricelist and the catalogue’s title page are the names of Aesthetic Dynamics members, with whom Ricks had established deep connections. Writers, dancers, visual and performing artists who served as teachers, cultural promoters, and social activists gathered to realize Afro-American Images 1971. Poet Lula Cooper published in Wilmington’s The People’s Pulse and was a member of the executive committee of the Concerned Citizens, a multiracial group dedicated to protesting businesses in Wilmington with discriminatory practices in the mid-1960s. Additionally an artist and civil and social justice activist, Cooper served as director of the YWCA Delaware, among other positions. Gertrude Jenkins was a graduate of Delaware State University, settling in Wilmington in 1960 to teach physical education and dance in the public school system. As an active member of Aesthetic Dynamics and Play Crafters, she became a well-known choreographer in Delaware and Pennsylvania. She taught at P.S. DuPont High School for several years and was there when Afro-American Images 1971 was staged. Also at the school was Carol Shrier Reed, an art teacher who shared an office with Ricks. Reed felt Ricks’s plans for Aesthetic Dynamics and the inaugural exhibition were significant, especially considering the recent National Guard occupation. Reed recalls Ricks speaking of the timeliness and urgency to celebrate Black creativity. As an Aesthetic Dynamics member, Reed traveled with Ricks to pick up work from participating artists and helped assemble the partition walls and install the show at the Wilmington Armory. Reed’s father, Alfred, and sister, Linda, assisted with fundraising and marketing of the exhibition.

Photograph of (left to right) Loïs Mailou Jones, Dr. Albert J. Carter, Delilah W. Pierce, and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of (left to right) Loïs Mailou Jones, Dr. Albert J. Carter, Delilah W. Pierce, and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

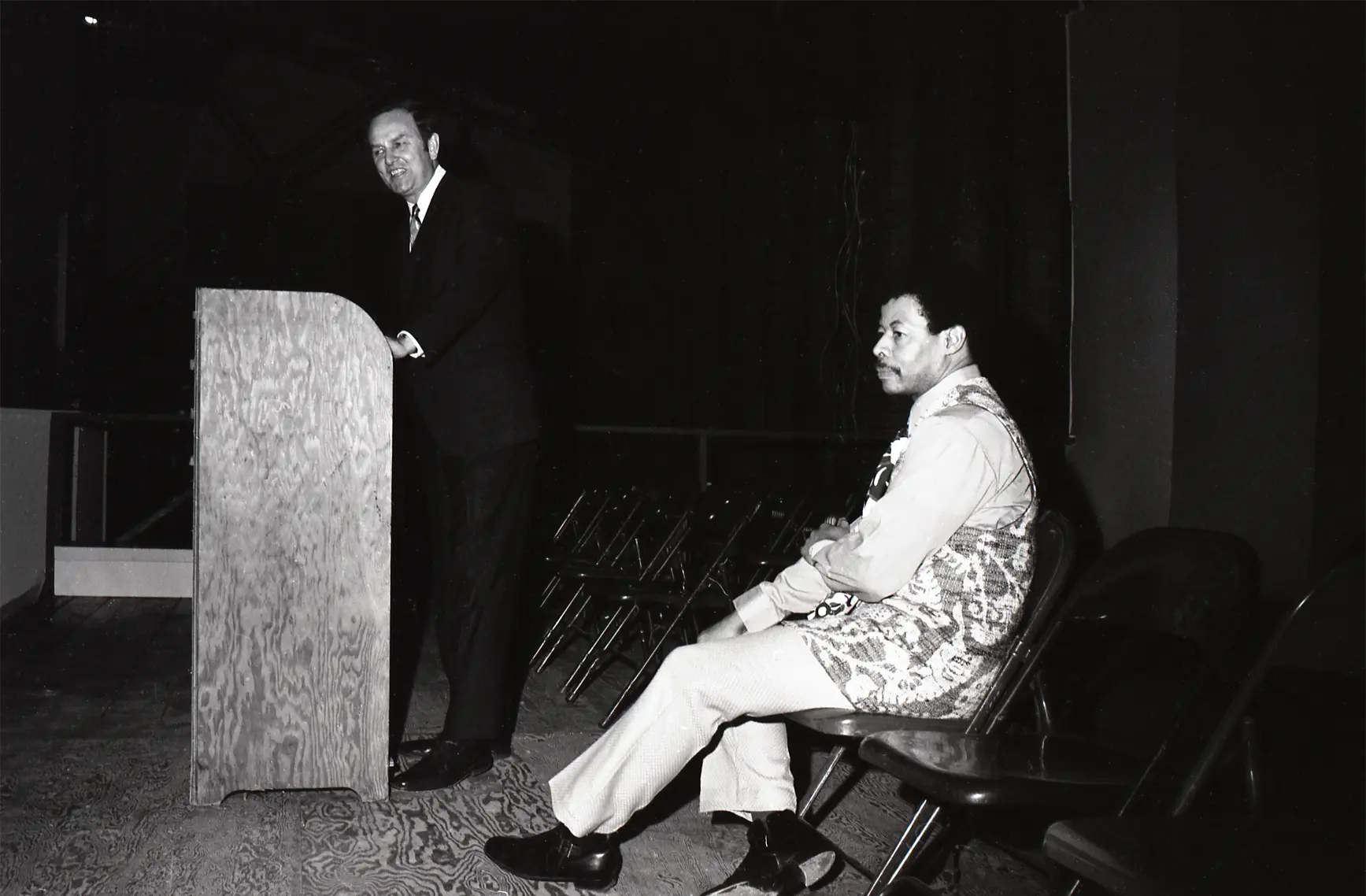

Photographer Woldemar Shock taught social studies at P. S. DuPont High School, where he met Ricks. In addition to assisting with the installation of Afro-American Images 1971 as an Aesthetic Dynamics member, Shock photographed the works of art for the exhibition catalogue and gathered invaluable documentation of the project, capturing the assembly of the show as well as the opening. Shock’s pictures comprise the greatest visual archive of the exhibition, showing how it was configured in the Wilmington Armory’s vast drill hall and capturing key individuals in attendance like Dr. Albert J. Carter, Loïs Mailou Jones, Delilah W. Pierce, Dorothy Porter, Alma Thomas, and Governor Russell W. Peterson, among others.

Aesthetic Dynamics member Jane Laskaris, on staff at Delaware State University, taught psychology, and her husband, painter Leo Laskaris, taught art at Stanton Central Elementary School. Member Barbara Greenhill was an art instructor at Tatnall School, and Simmie Knox—a key member and collaborator of Ricks—taught art at Howard High School with Robert C. Moore.

Photograph of Governor Russell W. Peterson and Percy Eugene Ricks during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of Governor Russell W. Peterson and Percy Eugene Ricks during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Perhaps the most fitting way to conclude this essay is by briefly acknowledging the longevity of Ricks’s creative undertaking. Aesthetic Dynamics continues to this day, 50 years after its founding, and over those many years, the collective has presented visual and performance arts programs that celebrate Black creativity. Ricks was explicit in asserting that Afro-American Images 1971 was not assembled for political purposes, but rather with the intention to “make the public, both [B]lack and white, aware of the wealth of artistic power and talent found in Black America.”[3] The group’s membership has grown, fed by arts educators and advocates like Arnold Hurtt, Rita Volkens, Valerie Kennedy, B. Ben Pearce, and Carl Vincent Williams. It is a living entity, a model that shifts to meet the needs of Delaware’s communities, utilizing the “creative use of the arts and science” as inspiration.

Margaret Winslow

Curator of Contemporary Art

Visit the Delaware Art Museum to see the restaging of Percy Ricks’ historic exhibition, co-presented with Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc. Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks is on view through January 23, 2022.

1. Percy Ricks, “The Wilmington Visual and Performing Arts Center,” 4, Rose Library, Emory University Archives, James A. Porter, collection no. 1139, box 43, folder 3.

2. Ruth Jillya Kaplan, “75 Black Artists—And Guard’s the Host,” Evening Journal (Wilmington, DE), January 26, 1971, 21.

3. Percy Ricks, “Introduction,” in Afro-American Images 1971 (Wilmington, DE: Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc.), 3.

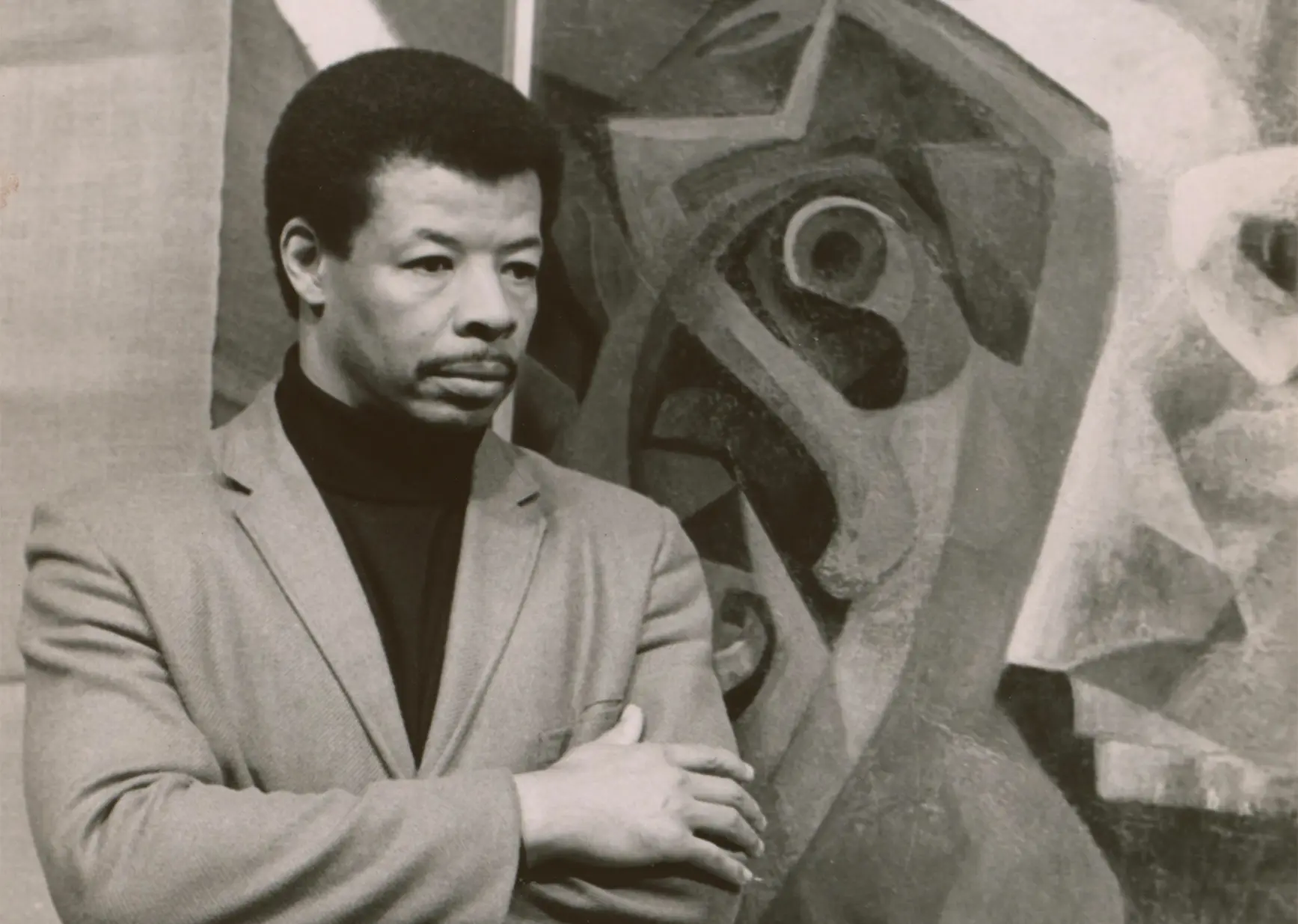

Top: Photograph of Percy Eugene Ricks with unknown painting, 1970. Courtesy of JENN and Associates.