Among the many cultural shifts and inventions of the Jazz Age, this period that spanned the 1920s and 1930s marked a transformative era for children’s literature in the United States. It was during this time that the concept of “childhood” as a distinct life stage gained prominence, leading to a cultural and educational development that recognized the unique needs of young learners. Key milestones such as the establishment of the Newbery Medal in 1922 and the Caldecott Medal in 1938 elevated the visibility and cultural value of children’s books and illustrations. This explosion and legitimization of children’s literature and illustration not only cemented a new industry and pathway for artists and storytellers but also empowered a generation of young learners with resources designed to engage them in this formative phase of life.

Today, we recognize the importance of supporting not only young learners, but community members looking to learn and grow their knowledge at all stages of life. Learning doesn’t begin and end in childhood. It spans a full spectrum, from early development to later adulthood. DelArt embraces its mission to serve as a resource in art and culture for all, and as we look toward 2025, we are excited to expand this commitment with new programs and expanded initiatives that further this work. By nurturing connections between art, culture, and education, we aim to inspire curiosity and empower creative thinkers across generations.

The Next Generation of Museum-Goers: Art and Learning for Early Childhood

One of our ongoing efforts to be a greater resource for young learners and families involves enhancing access to our collection of children’s literature. This year, our Art & Learning department has been meticulously cataloging all the children’s books throughout the Museum, to add them to our library catalogue and make them more easily searchable and retrievable. This effort will not only allow us to maintain a more detailed inventory and accounting of all the books for young learners that we have available in Kids’ Corner and other parts of the Museum, but it will also help us to identify areas of growth in our collection. As well, this project is laying the groundwork for a lending library in our Kids’ Corner, enabling children and families to borrow books and explore the magic of storytelling beyond their museum visit, a program we’re excited to roll out in 2025. By creating this resource, we are building on the Museum’s foundational bonds to narrative art and storytelling, fostering a love for reading and art while reinforcing the museum as a welcoming space for young visitors to discover, learn, and grow.

Empowering Our Creative Economy: The Museum Educator Development Program

Our dedication to learning extends to older learners in young adults and emerging professionals, through the Museum Educator Development Program. Inaugurated in 2019, this year-long program provides recent graduates and creatives interested in getting more experience in the museum world the opportunity to gain exposure and build the skills that will help them on their career path in the arts and culture sector. Members of our Museum Educator cohort not only learn fundamental methods and concepts of museum education (a week-long orientation trains them on subjects like childhood cognitive development stages and object-based facilitation), but they also have the opportunity to put them into practice by leading tours and developing tour curricula for learners of all ages. This past summer, our current cohort undertook an ambitious project to review and refurbish our tours for K-12 school visits, elevating them into fun and interactive gallery experiences with strong connections to Common Core State Standards. In addition to the robust training and development they receive in museum education, the Museum Educator program is designed to give each Educator the opportunity for broader career exploration and skill-building by taking on additional projects in other areas of the Museum. Participants in this year’s cohort are assisting with exhibition design, facilitating gallery talks alongside our curators, and helping to develop innovative new community programming.

With the recent losses of key art institutions locally and in the region, with the closures of DCAD, University of the Arts, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts degree program, it is more vital than ever that our organization does its part to be a support and resource for young adults and creatives looking to build a sustainable future in the arts. By equipping them with professional opportunities and training, this program strengthens Delaware’s creative economy and expands access to museum careers, building the next generation of leaders in art and culture.

A New Chapter: The Loper Society for Lifelong Learners

In 2025, we will launch the Loper Society for Lifelong Learners, a new initiative and model for adult education and enrichment that is dedicated to fostering deep connection and meaningful experience in the arts. Taking cues from another type of cultural institution, colleges and universities, the program will consist of community-led clubs and special interest groups, to build a vibrant community of adult learners passionate about arts and culture. This program will offer workshops, lectures, and hands-on experiences tailored to prime adult learners eager for a robust social and cultural outlet within the Museum. The Loper Society is an exciting step forward in our efforts to broaden access to art and foster meaningful engagement with our collection and across the state.

As the museum continues to grow and innovate, we remain steadfast in our commitment to lifelong learning. Through art and education, we strive to be a cultural hub where visitors of every age can learn, connect, and thrive.

Zoe Akoto

Manager of Learning and Interpretation

Image: Children’s Book Week, November 12th to 18th, 1922. Jessie Willcox Smith (1863–1935). Advertising poster for Children’s Book Week, November 12th to 18th, 1922. Commercial lithograph, sheet: 21 3/16 × 13 7/16 inches. Found in collection.

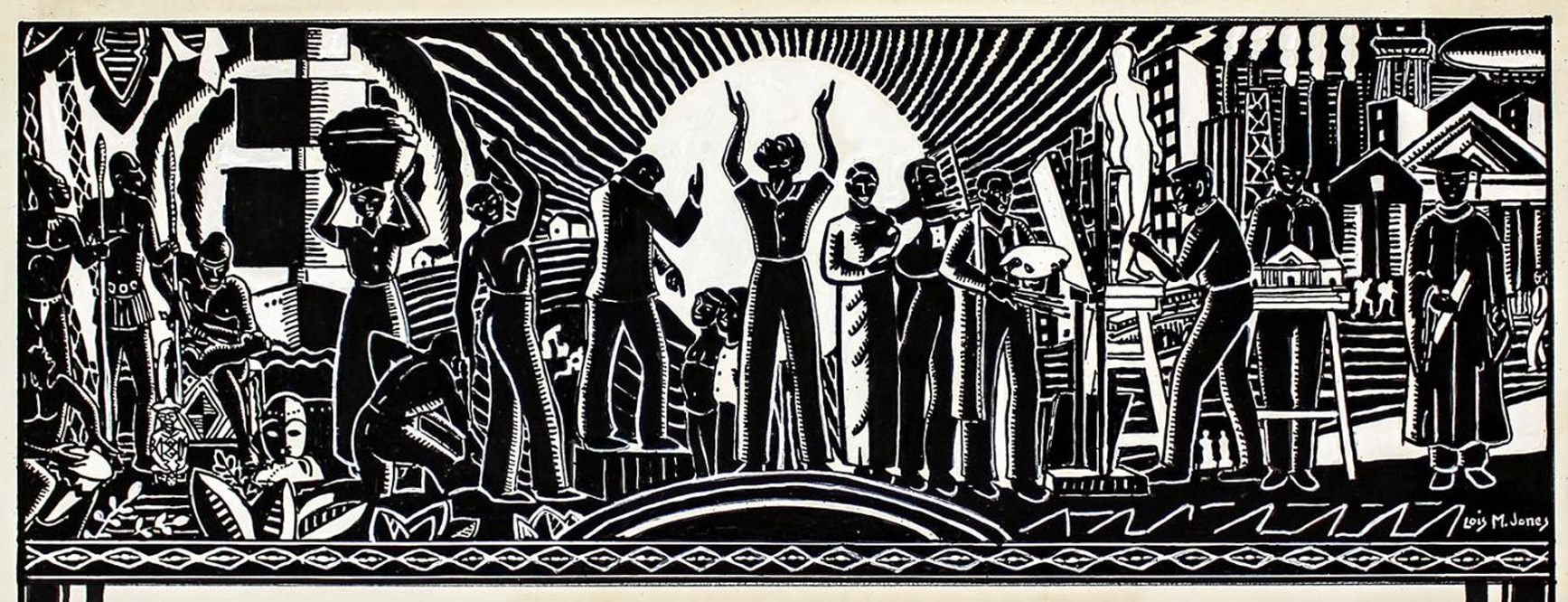

Heritage: Illustration for Important Events and Dates in Negro History, 1936. Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Brush and ink over lithograph on paper, 7 ½ x 19 ¼ inches. The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina.

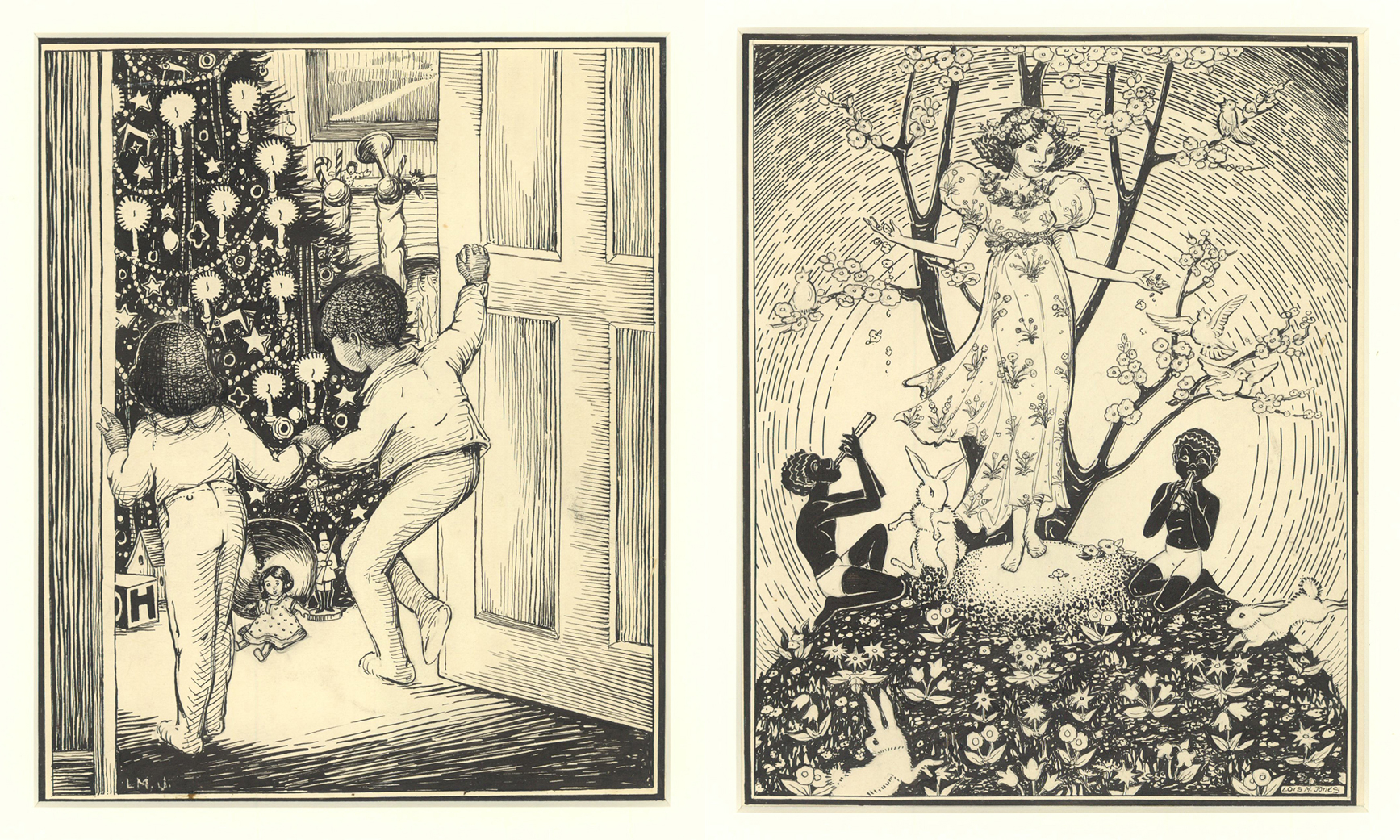

Heritage: Illustration for Important Events and Dates in Negro History, 1936. Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Brush and ink over lithograph on paper, 7 ½ x 19 ¼ inches. The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina.  Left to right: My Christmas Tree, 1935. For The Picture-Poetry Book by Gertrude Parthenia McBrown (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, Inc., 1935). Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Ink on paper, 11 ¾ x 8 ¾ inches. University of Findlay’s Mazza Museum. The Voice of Spring, 1935. For The Picture-Poetry Book by Gertrude Parthenia McBrown (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, Inc., 1935). Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Ink on paper, 11 ¾ x 8 ¾ in. University of Findlay’s Mazza Museum.

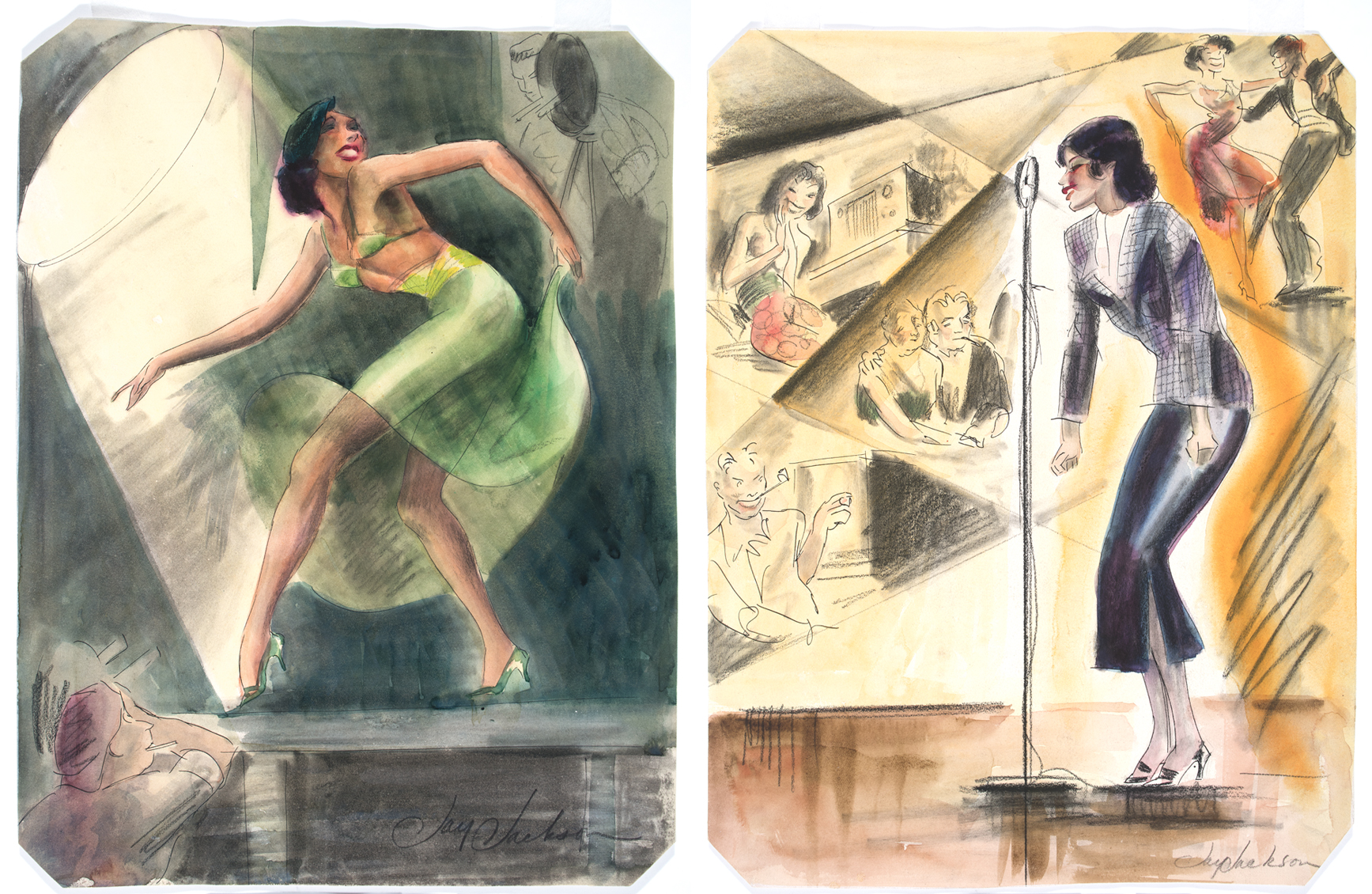

Left to right: My Christmas Tree, 1935. For The Picture-Poetry Book by Gertrude Parthenia McBrown (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, Inc., 1935). Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Ink on paper, 11 ¾ x 8 ¾ inches. University of Findlay’s Mazza Museum. The Voice of Spring, 1935. For The Picture-Poetry Book by Gertrude Parthenia McBrown (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, Inc., 1935). Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Ink on paper, 11 ¾ x 8 ¾ in. University of Findlay’s Mazza Museum.  Left to right: Etta Moten Barnett Dancing, c. 1940. Jay Jackson (1905–1954). Watercolor, ink, and charcoal on paper, 12 5/8 x 9 5/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2022. Etta Moten Barnett Singing, c. 1940. Jay Jackson (1905–1954). Watercolor, ink, and charcoal on paper, 12 5/8 x 9 9/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2022.

Left to right: Etta Moten Barnett Dancing, c. 1940. Jay Jackson (1905–1954). Watercolor, ink, and charcoal on paper, 12 5/8 x 9 5/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2022. Etta Moten Barnett Singing, c. 1940. Jay Jackson (1905–1954). Watercolor, ink, and charcoal on paper, 12 5/8 x 9 9/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2022.  Left to right: John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, September 15, 1927. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, June 3, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

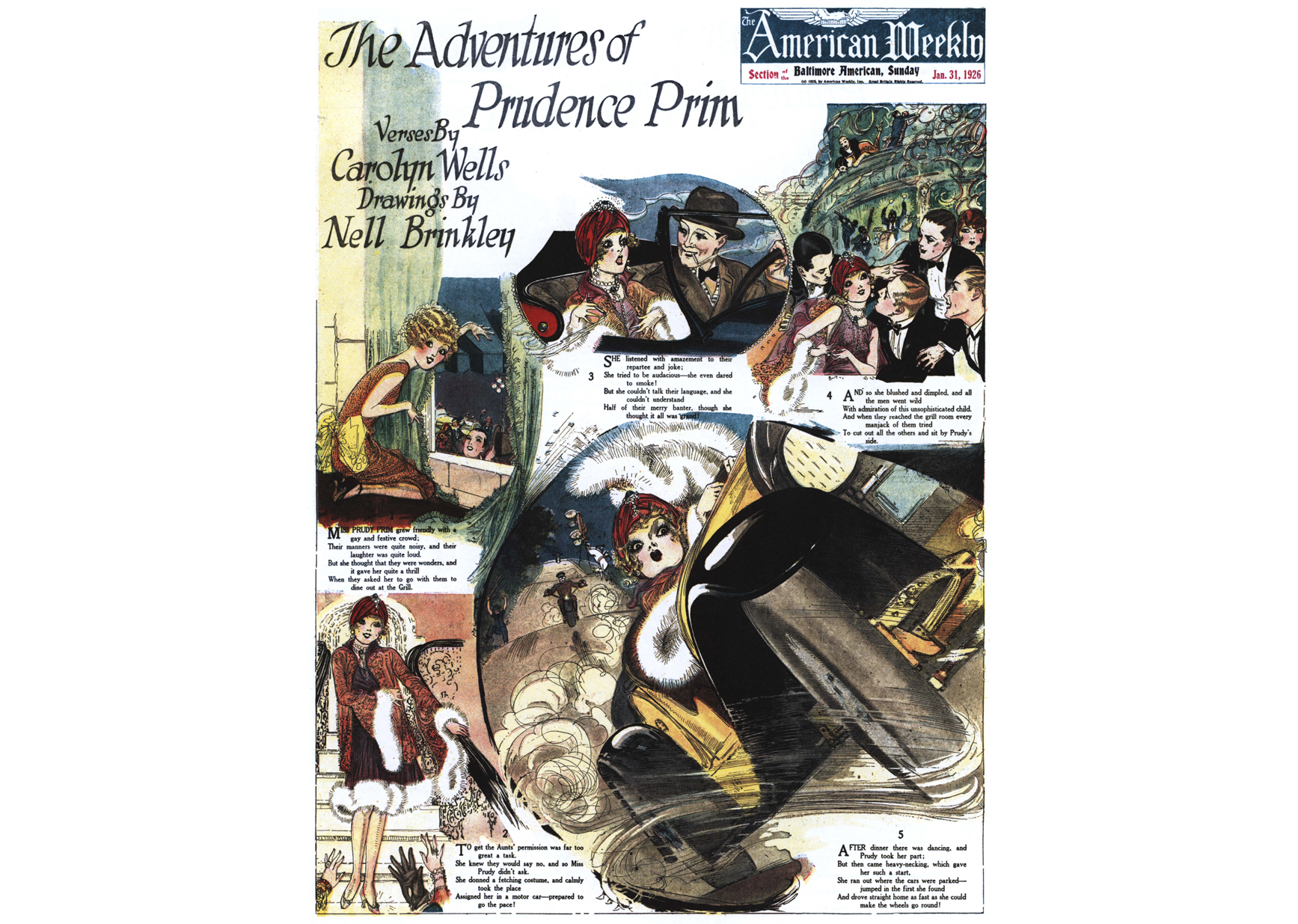

Left to right: John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, September 15, 1927. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. John Held, Jr. (1889-1958), cover for Life, June 3, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Nell Brinkley (1886-1944), The Adventures of Prudence Prim, from American Weekly, Chicago Herald and Examiner, January 31, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

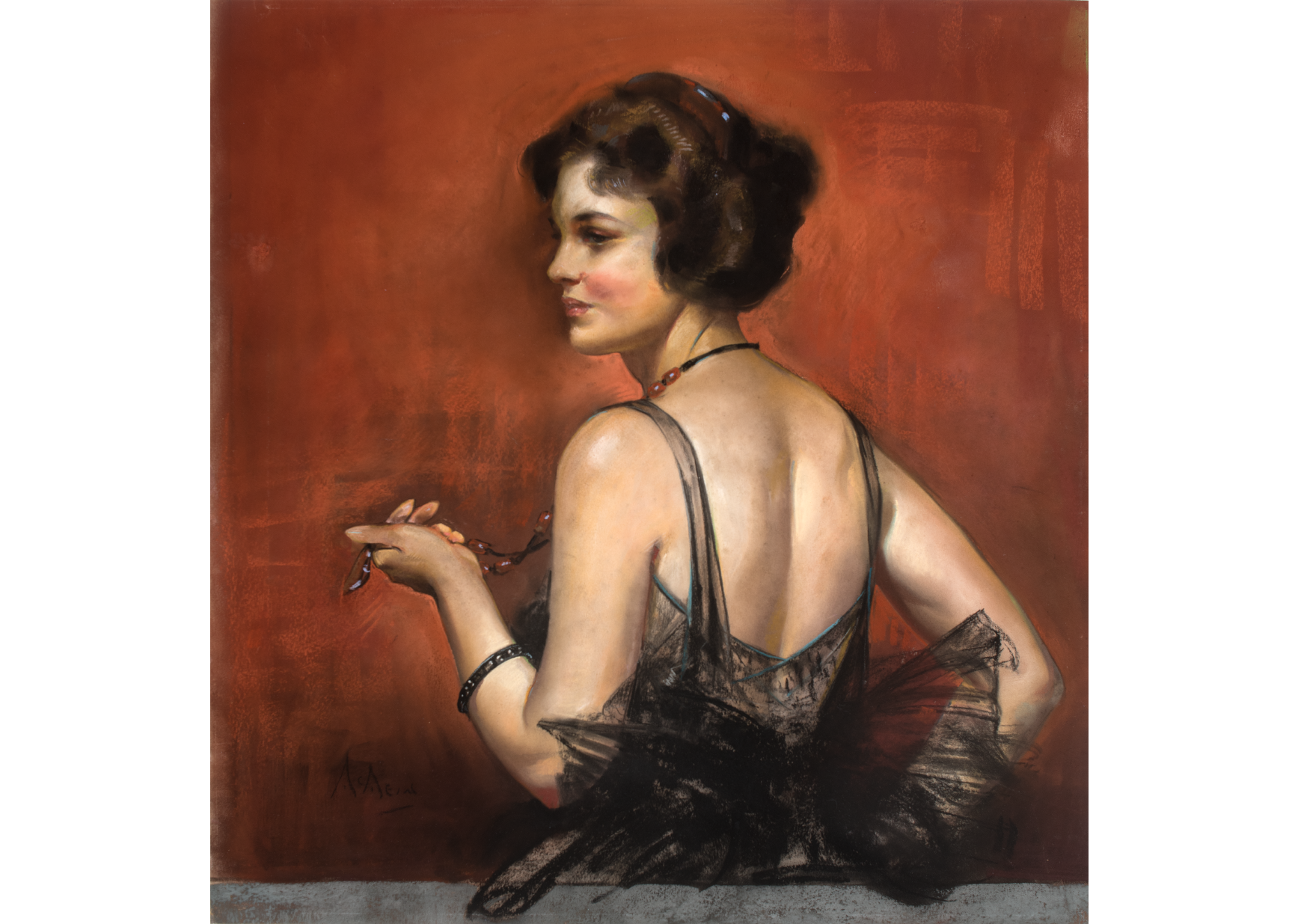

Nell Brinkley (1886-1944), The Adventures of Prudence Prim, from American Weekly, Chicago Herald and Examiner, January 31, 1926. Printed matter. Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. The Admirable Hostess, from Advertisement for Wallace Silver, published in The Saturday Evening Post, January 8, 1921. Neysa Moran McMein (1888–1949). Pastel on board, 30 1/8 × 28 5/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2022.

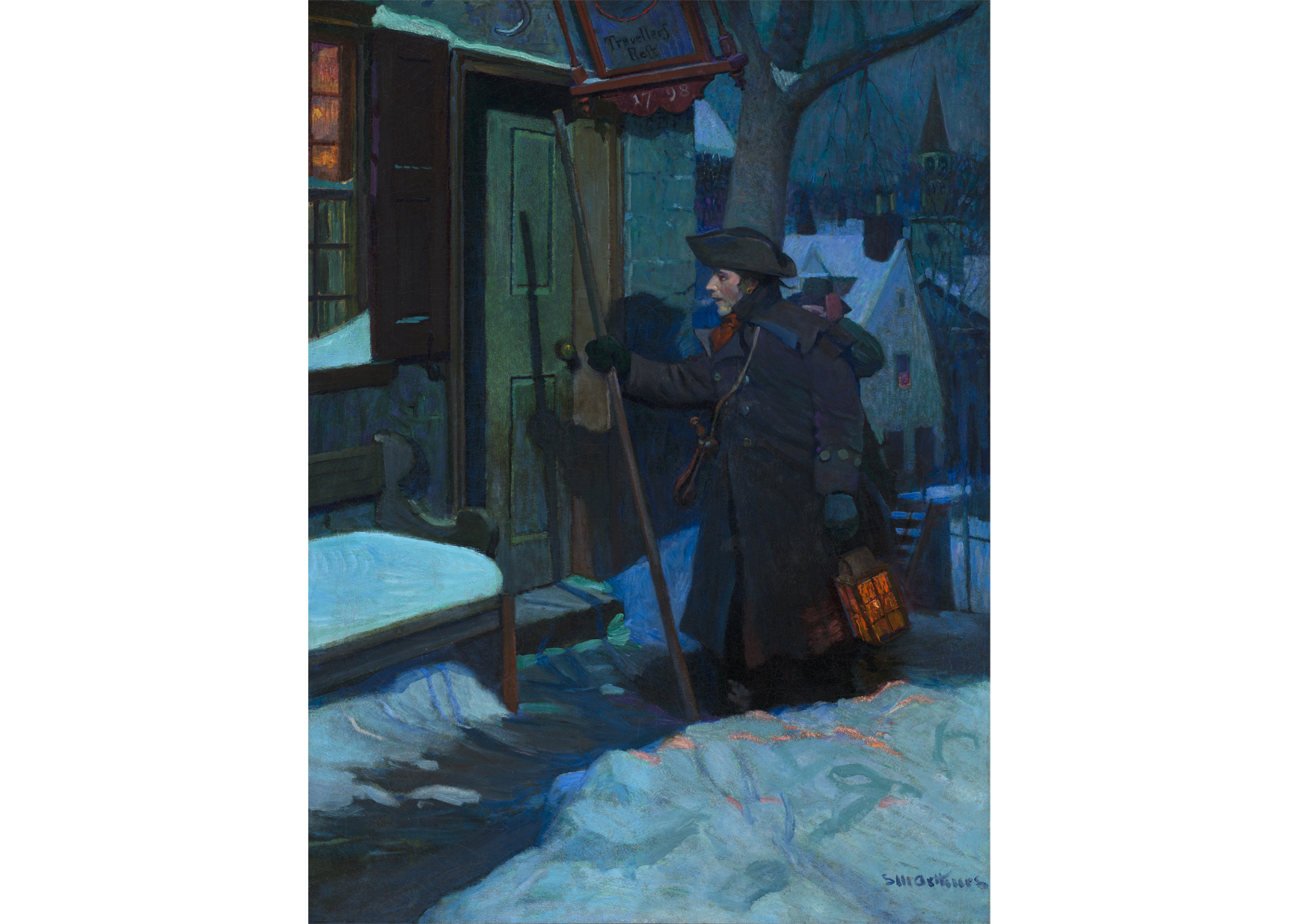

The Admirable Hostess, from Advertisement for Wallace Silver, published in The Saturday Evening Post, January 8, 1921. Neysa Moran McMein (1888–1949). Pastel on board, 30 1/8 × 28 5/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2022. New Year’s Eve, for an advertising calendar for Brown & Bigelow, 1928. Stanley Arthurs (1877–1950). Oil on canvas, 35 ½ x 26 3/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Louis du Pont Copeland Memorial Fund, 1930.

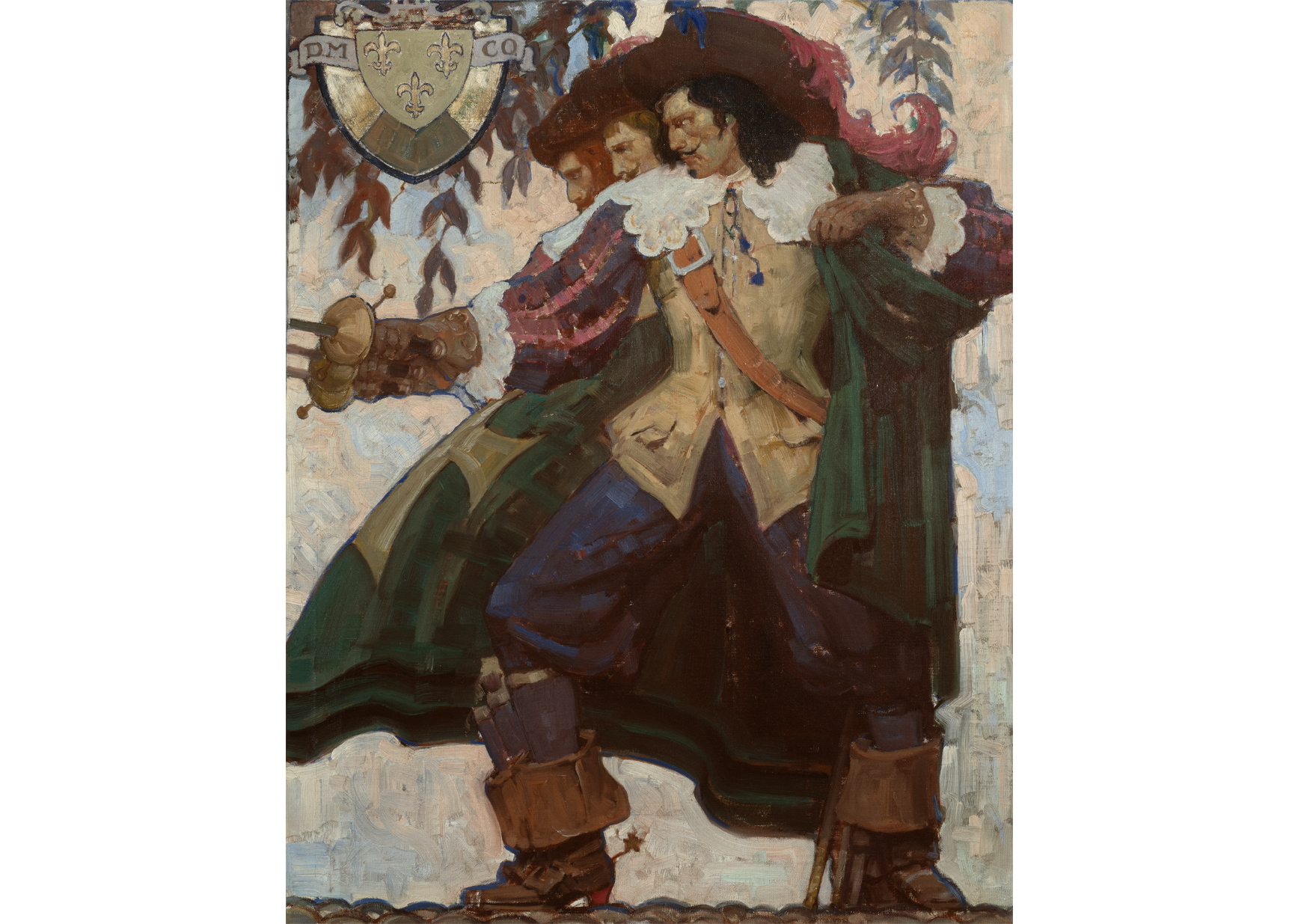

New Year’s Eve, for an advertising calendar for Brown & Bigelow, 1928. Stanley Arthurs (1877–1950). Oil on canvas, 35 ½ x 26 3/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Louis du Pont Copeland Memorial Fund, 1930.  Cover for The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas (Boston: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1929). Mead Schaeffer (1898–1980). Oil on canvas, 32 x 26 inches. Collection of Brock and Yvonne Vinton.

Cover for The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas (Boston: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1929). Mead Schaeffer (1898–1980). Oil on canvas, 32 x 26 inches. Collection of Brock and Yvonne Vinton. L’Amour Irresistible, 1896. Maria Zambaco (1843–1914). Spelter, patinated bronze, and gold. F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2022.

L’Amour Irresistible, 1896. Maria Zambaco (1843–1914). Spelter, patinated bronze, and gold. F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2022.  The Resurrection: Why seek Ye the Living among the Dead; In those days Mary rose in haste and fled into the hill country, 1888. Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936). Each panel: 7 1/2 × 8 3/4 in. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund in honor of Thomas Clarkson Taylor Brokaw, 2023.

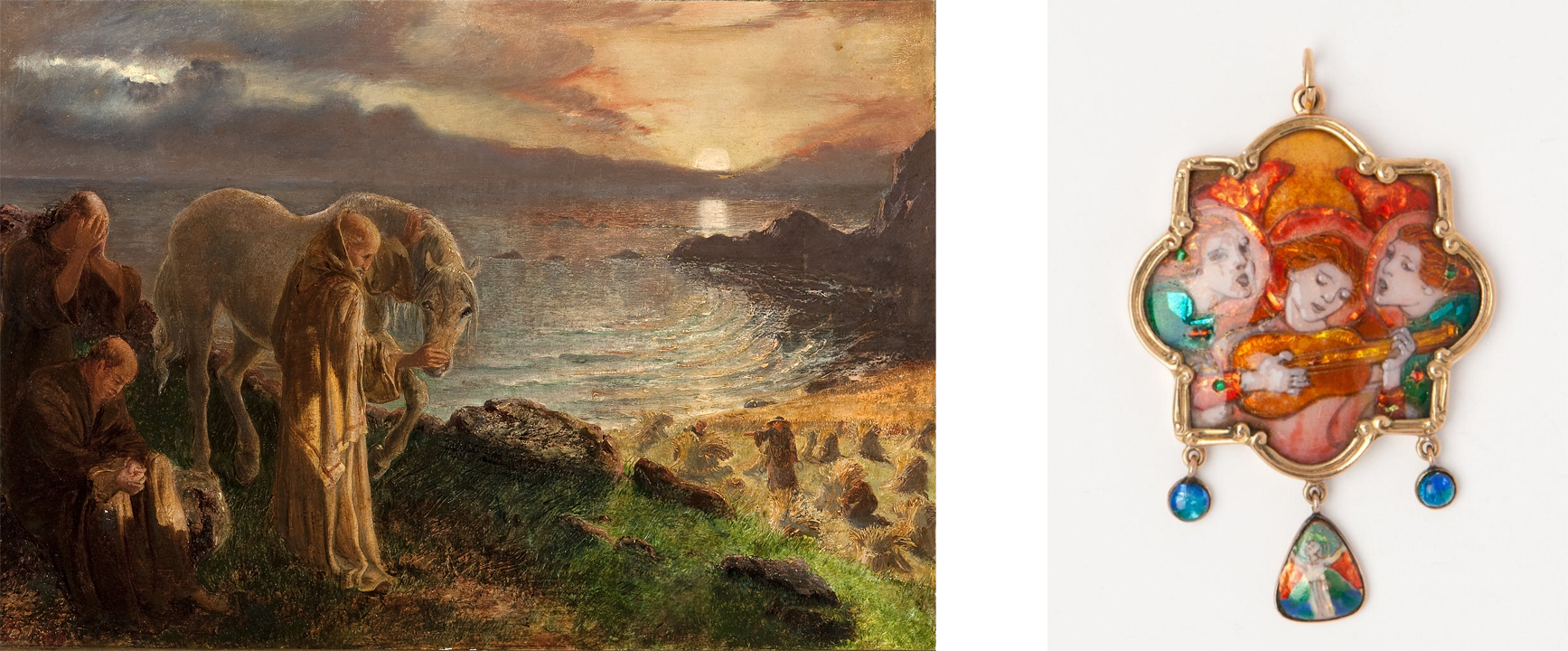

The Resurrection: Why seek Ye the Living among the Dead; In those days Mary rose in haste and fled into the hill country, 1888. Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936). Each panel: 7 1/2 × 8 3/4 in. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund in honor of Thomas Clarkson Taylor Brokaw, 2023. Pendant: The Song, 1904. Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936). Polychrome enamel and silver foil on copper set in gold. 2 1/8 × 1 7/8 in. (5.4 × 4.8 cm). Gift of Mrs. H. W. Janson, 1976.

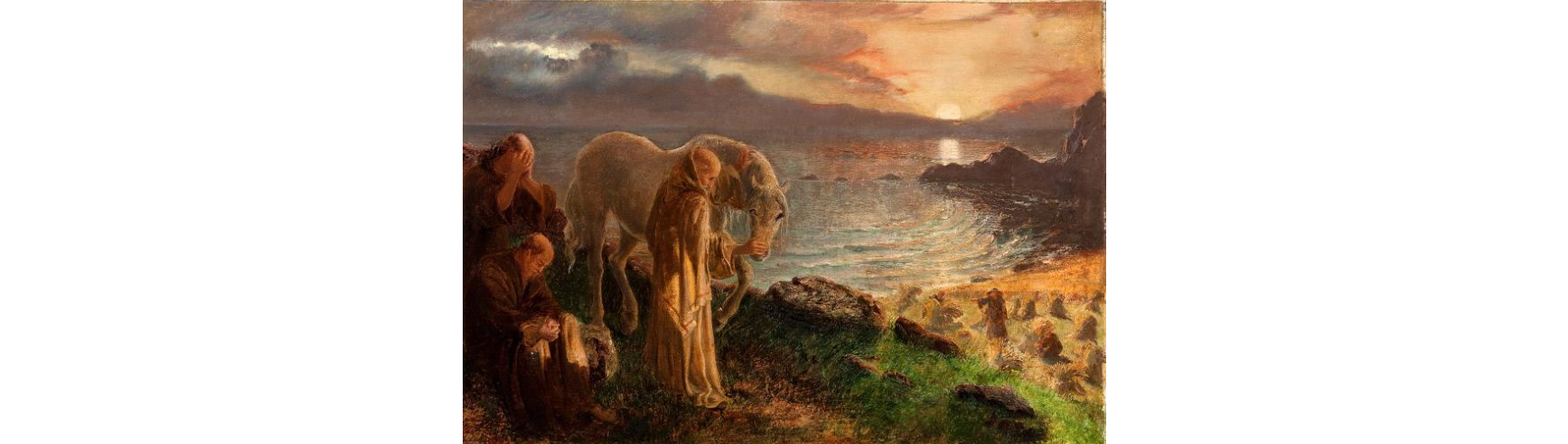

Pendant: The Song, 1904. Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936). Polychrome enamel and silver foil on copper set in gold. 2 1/8 × 1 7/8 in. (5.4 × 4.8 cm). Gift of Mrs. H. W. Janson, 1976.  St. Columba’s Farewell to the White Horse, 1868. Alice Boyd (1825–1897). Oil on board, 7/8 × 19 7/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2011.

St. Columba’s Farewell to the White Horse, 1868. Alice Boyd (1825–1897). Oil on board, 7/8 × 19 7/8 inches. Acquisition Fund, 2011.  Four renderings of possible designs for the Delaware Art Museum by Victorine and Samuel Homsey, 1937.

Four renderings of possible designs for the Delaware Art Museum by Victorine and Samuel Homsey, 1937.  Book Jacket for No Nice Girl Swears by Alice-Leone Moats (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1933). Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

Book Jacket for No Nice Girl Swears by Alice-Leone Moats (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1933). Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

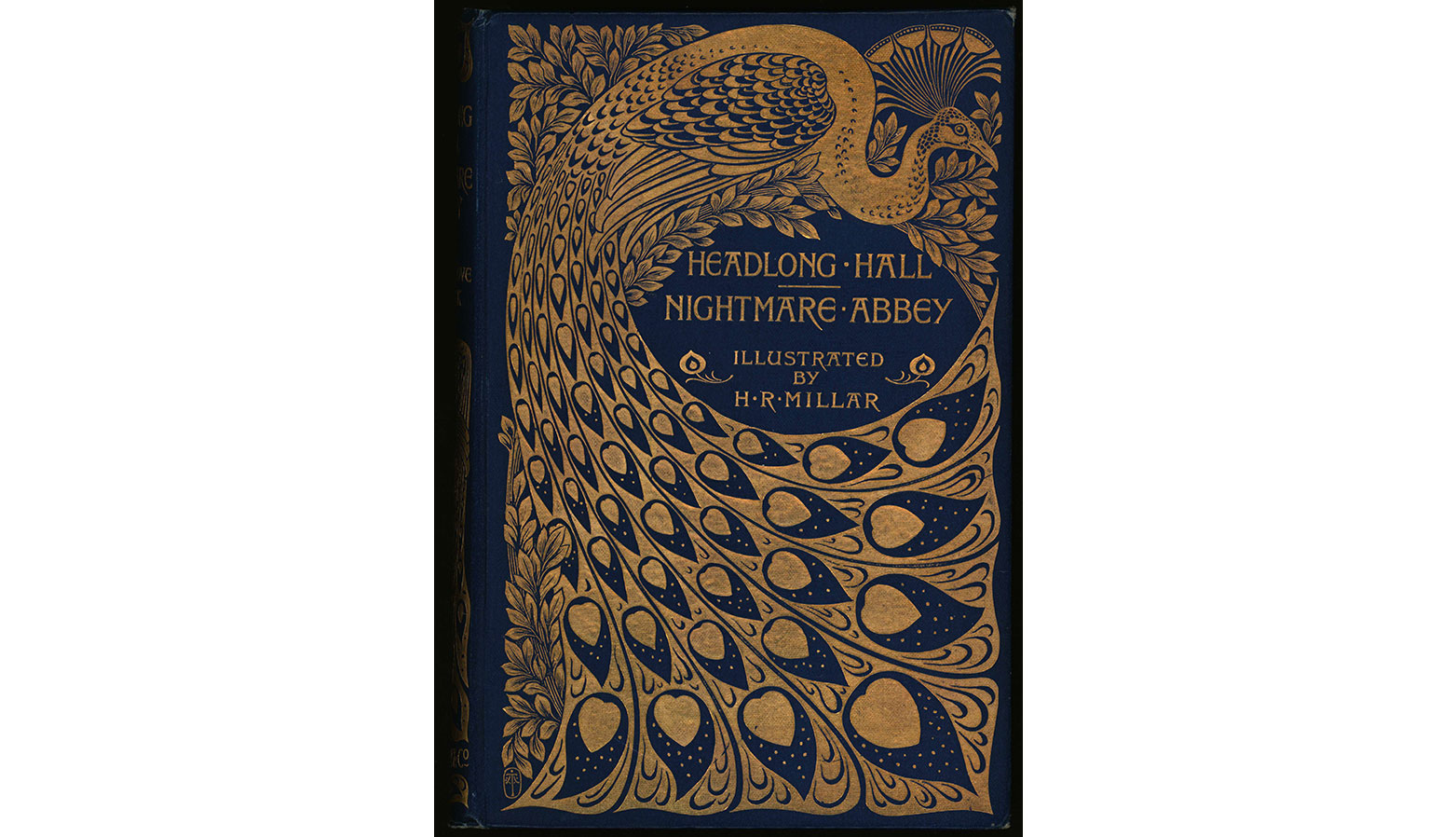

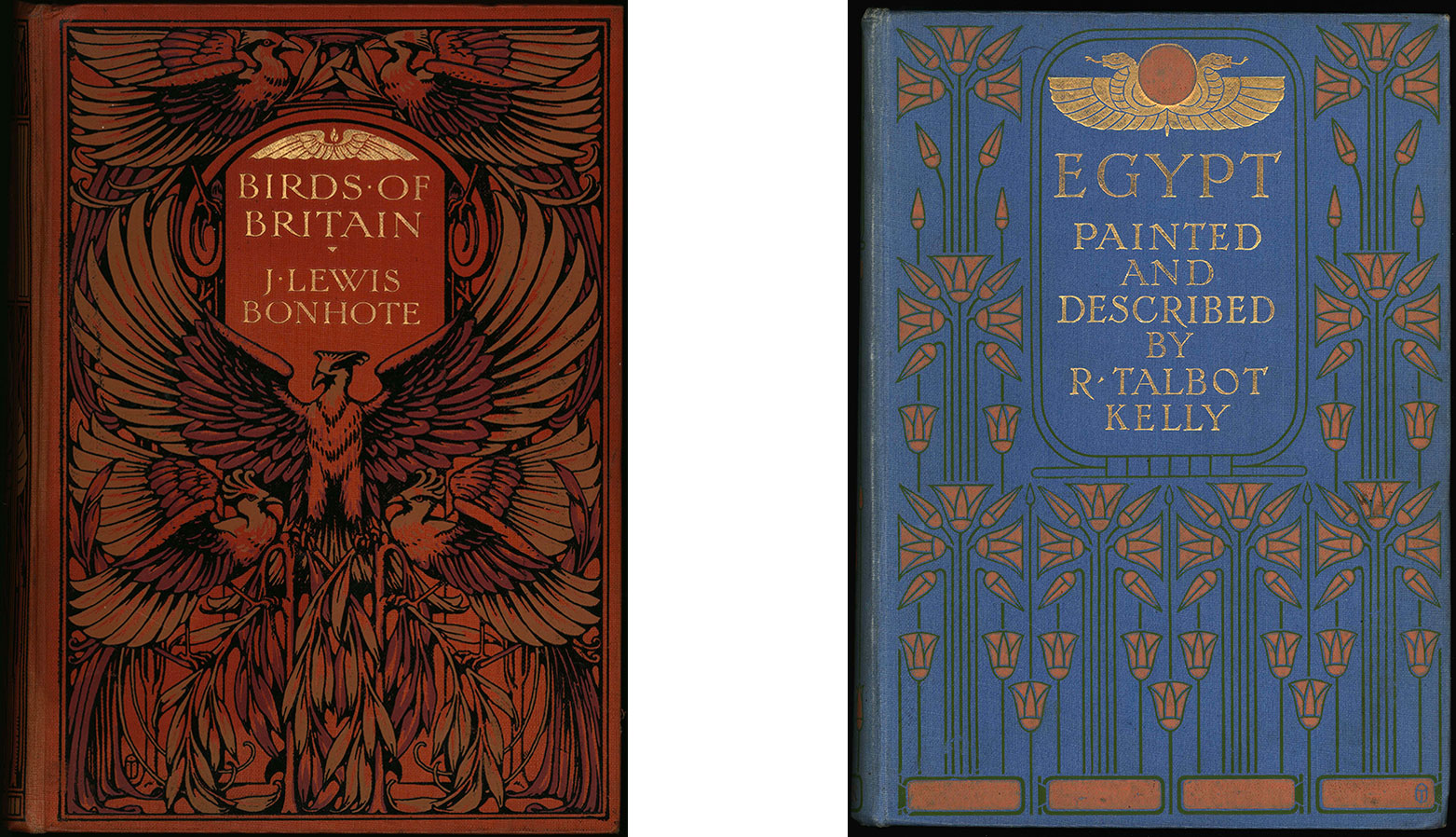

F. Berkeley Smith (1869-1931), binding for The Real Latin Quarter, by F. Berkeley Smith (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1901). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941), binding for The Violet Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang (London: Longman’s, Green, and Co., 1901). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

F. Berkeley Smith (1869-1931), binding for The Real Latin Quarter, by F. Berkeley Smith (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1901). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941), binding for The Violet Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang (London: Longman’s, Green, and Co., 1901). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Margaret Armstrong (1867-1944), binding for Pippa Passes, by Robert Browning (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1903). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. A Woman of the World, by Ella Wheeler Wilcox (Boston: L. C. Page, 1905). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

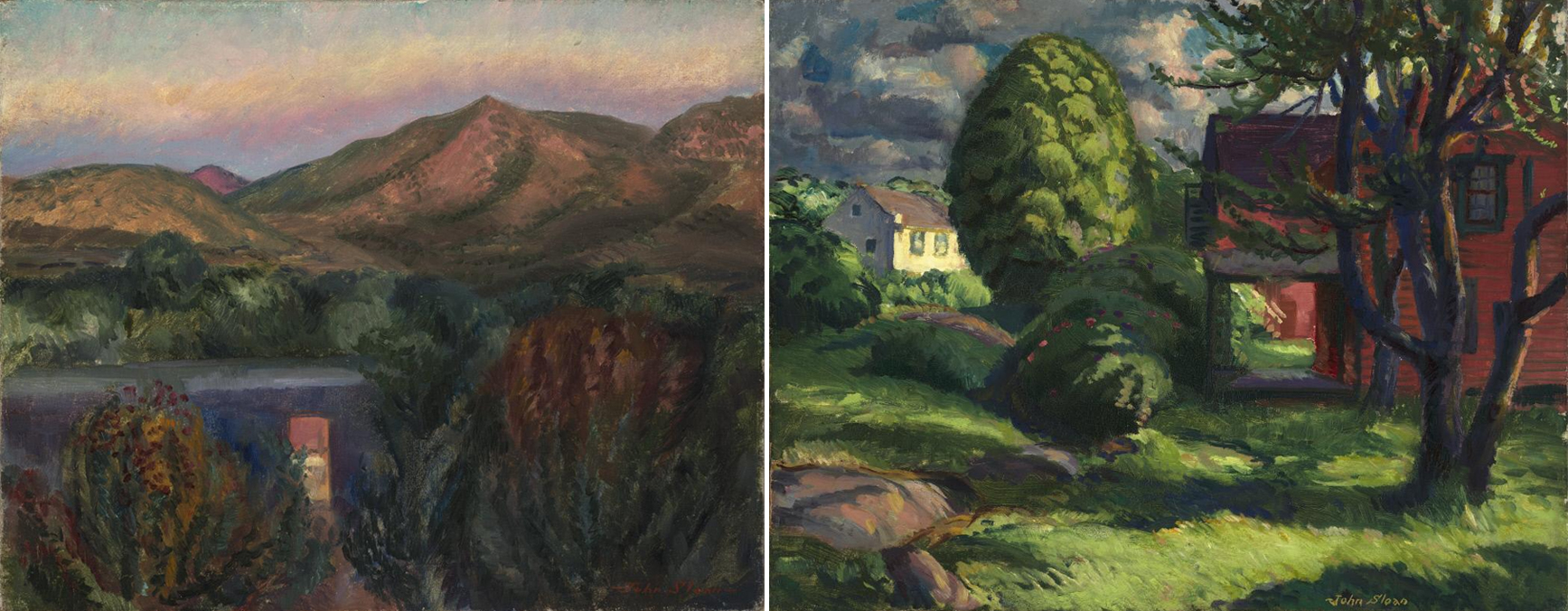

Margaret Armstrong (1867-1944), binding for Pippa Passes, by Robert Browning (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1903). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. A Woman of the World, by Ella Wheeler Wilcox (Boston: L. C. Page, 1905). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Left to right: Our Home, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, I, 1910. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on linen mounted to board, 8 1/2 × 10 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1980.

© Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Green Grass and Purple Rocks, 1915. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 × 24 1/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of H. Beatty Chadwick, 1982. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Left to right: Our Home, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, I, 1910. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on linen mounted to board, 8 1/2 × 10 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1980.

© Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Green Grass and Purple Rocks, 1915. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 × 24 1/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of H. Beatty Chadwick, 1982. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.  Left to right: East at Sunset, Kitchen Door, 1920. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 16 × 20 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Long Shadows, 1918. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 20 × 26 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Left to right: East at Sunset, Kitchen Door, 1920. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 16 × 20 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Long Shadows, 1918. John Sloan (1871–1951). Oil on canvas, 20 × 26 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

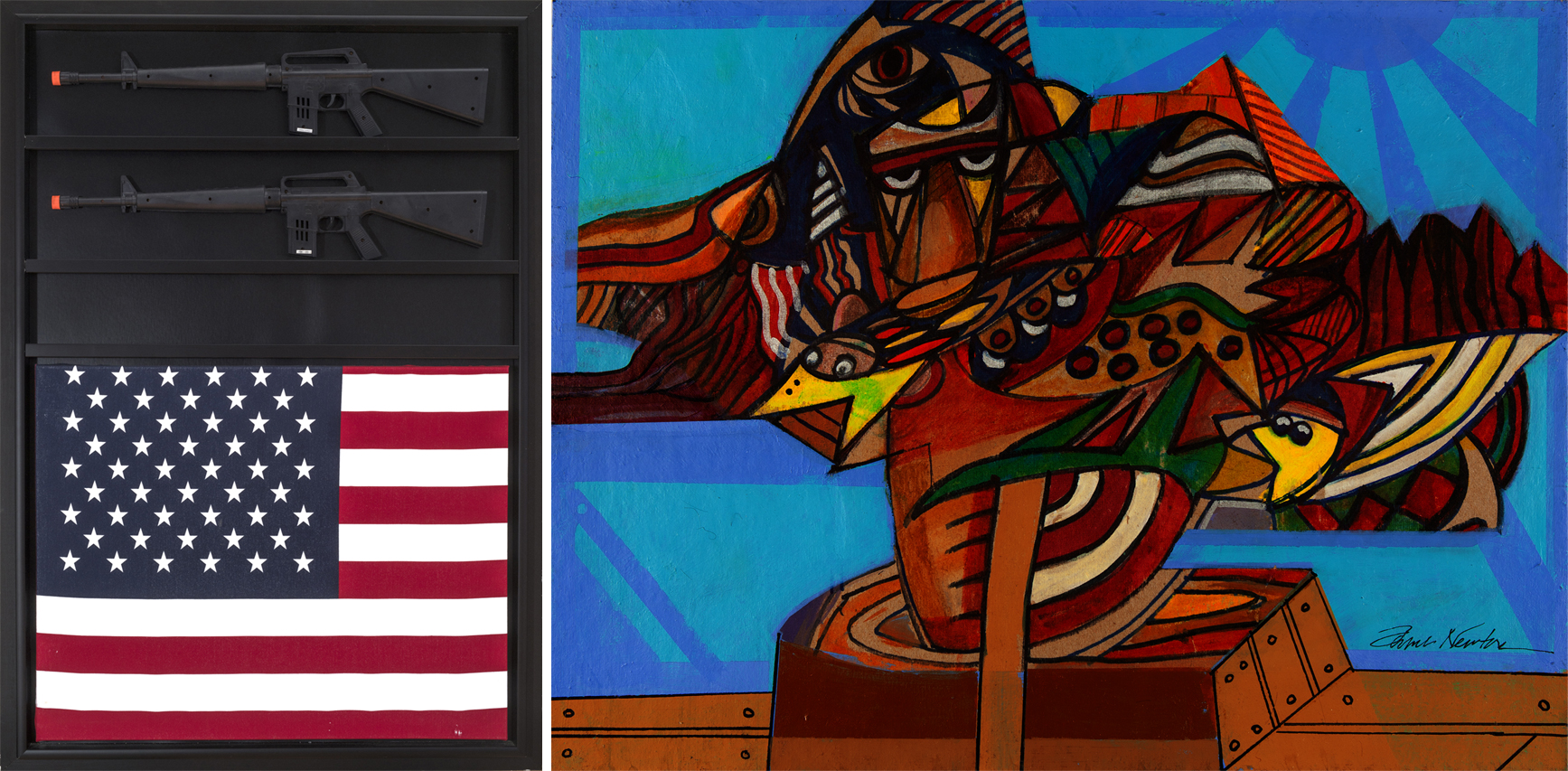

Left: American Sixties II, c. 1970. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media assemblage, 49 5/8 x 34 5/8 x 4 1/2 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: They Came Before Columbus VI, 2007. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Ink and acrylic on board, 12 × 16 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Left: American Sixties II, c. 1970. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media assemblage, 49 5/8 x 34 5/8 x 4 1/2 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: They Came Before Columbus VI, 2007. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Ink and acrylic on board, 12 × 16 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Left: Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 40 × 36 1/4 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Middle: Mausoleum of Lazarus, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on board, 31 3/4 × 24 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: Don Quixote, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 23 × 15 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

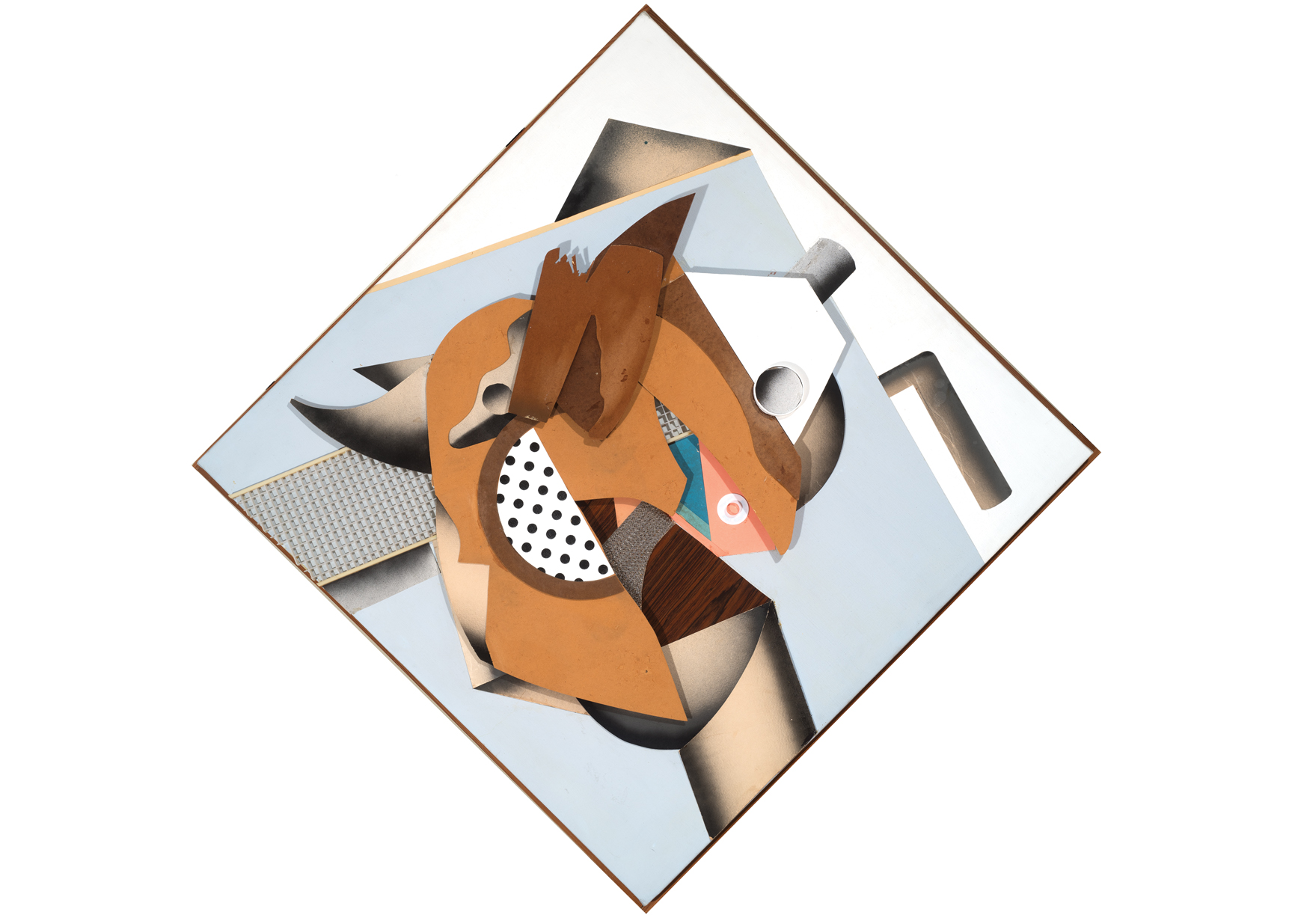

Left: Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 40 × 36 1/4 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Middle: Mausoleum of Lazarus, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on board, 31 3/4 × 24 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton. Right: Don Quixote, 1966. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media on canvas, 23 × 15 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.  Piggly Wiggly, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media, 42 × 41 1/4 × 7 inches, support: 57 1/2 × 56 1/2 × 7 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Piggly Wiggly, 1967. James E. Newton (1941–2022). Mixed media, 42 × 41 1/4 × 7 inches, support: 57 1/2 × 56 1/2 × 7 inches. Private Collection. © Estate of James E. Newton.

Tight, 1993. Sharon Louden (born 1964). Ink and graphite on double sided mylar, 11 × 8 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2009. © Sharon Louden.

Tight, 1993. Sharon Louden (born 1964). Ink and graphite on double sided mylar, 11 × 8 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2009. © Sharon Louden. Untitled, 1998. Alyson Shotz (born 1964). Mixed media on paper, 9 × 12 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2009. © Alyson Shotz.

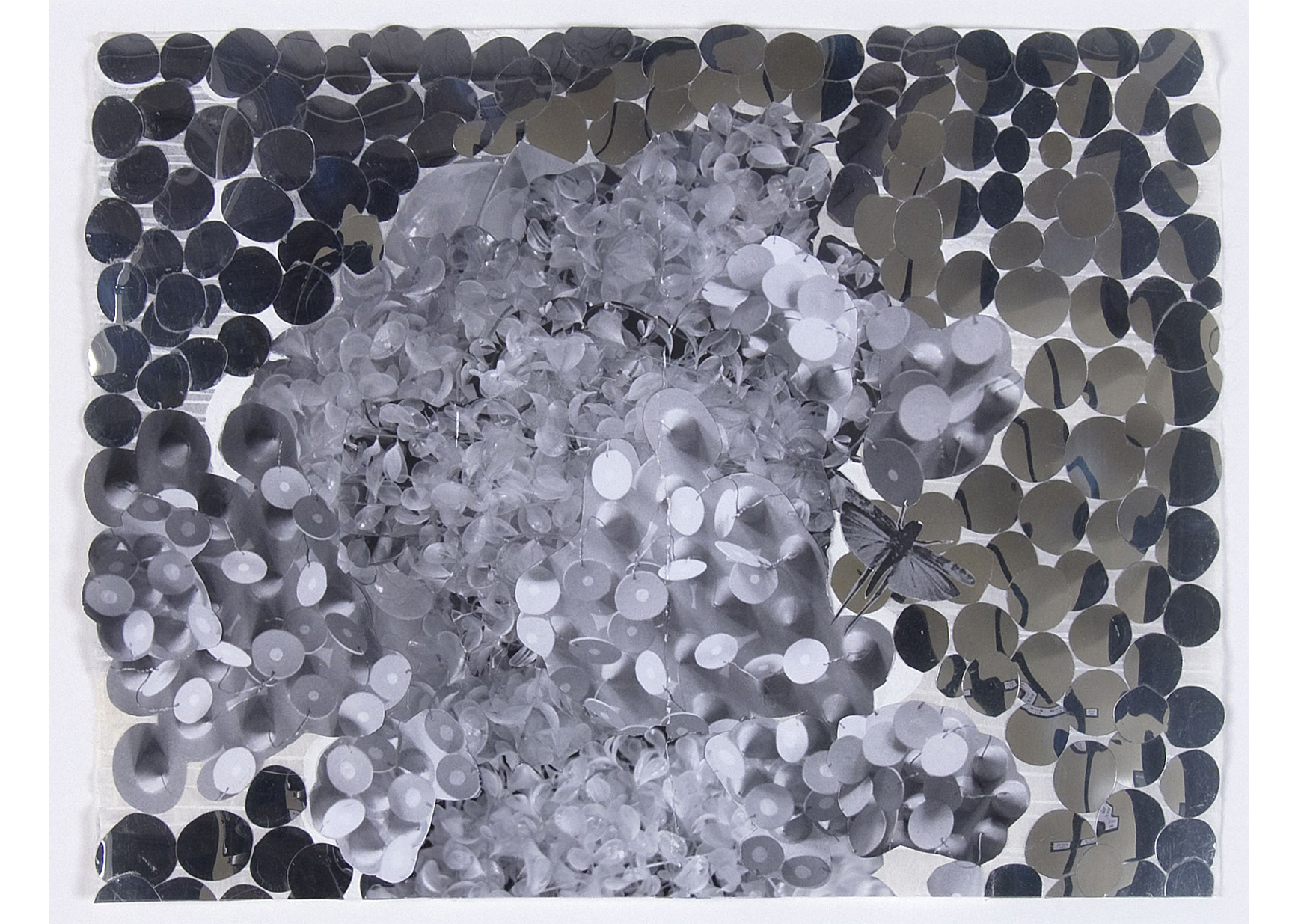

Untitled, 1998. Alyson Shotz (born 1964). Mixed media on paper, 9 × 12 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2009. © Alyson Shotz. Mars Wanderings (detail)

Mars Wanderings (detail) According to what, 2023. David Meyer (born 1963). Steel, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist. © David Meyer. Photo by Shannon Woodloe.

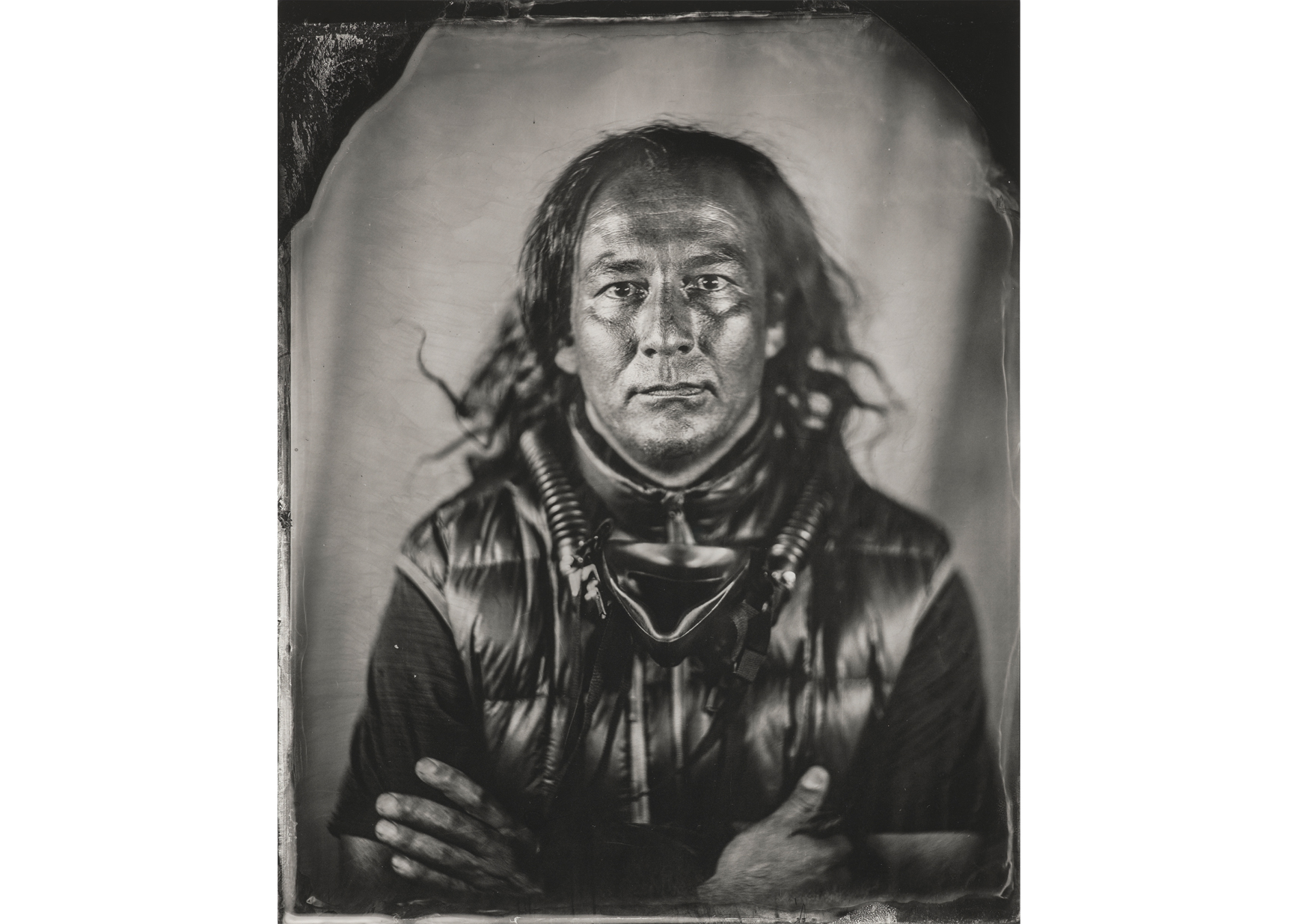

According to what, 2023. David Meyer (born 1963). Steel, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist. © David Meyer. Photo by Shannon Woodloe. Laura Briggs Photography.

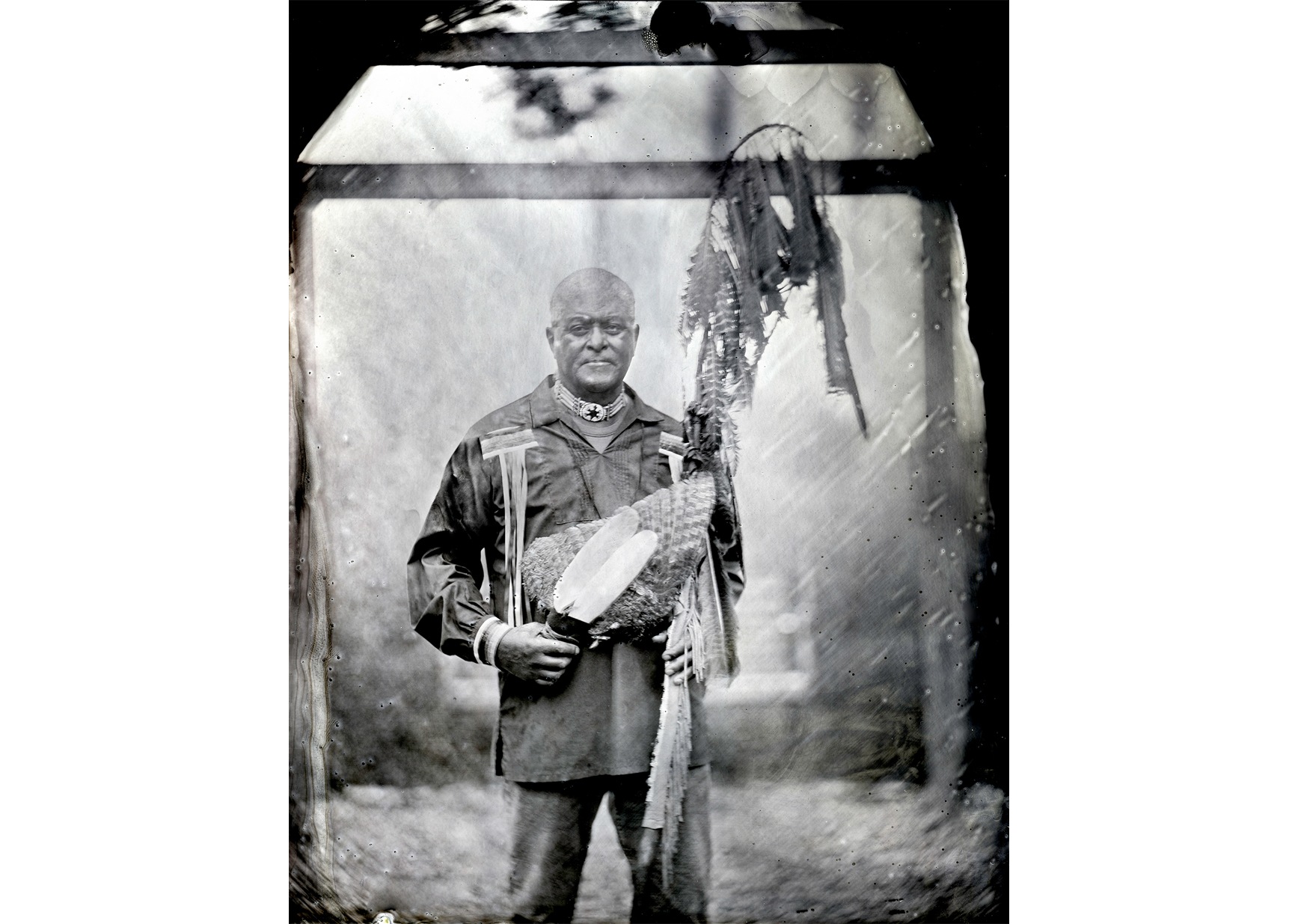

Laura Briggs Photography. Meghan Newberry Photography. Sculpture:

Meghan Newberry Photography. Sculpture:

Kaleidoscope Cove was designed by the Volta Family in 2016.

Kaleidoscope Cove was designed by the Volta Family in 2016. Lenny the Ice Cream Man was dreamed up by the Smith Family in 2017.

Lenny the Ice Cream Man was dreamed up by the Smith Family in 2017. Creative Power was the work of the Silverman Family in 2018.

Creative Power was the work of the Silverman Family in 2018.

Glorious Truth (part 2) River Reporter, August 2022 (2), 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Metallic paint on newspaper, 12 13/16 × 19 7/8 inches. sheet: 13 5/8 × 20 7/8 in. (34.6 × 53 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott.

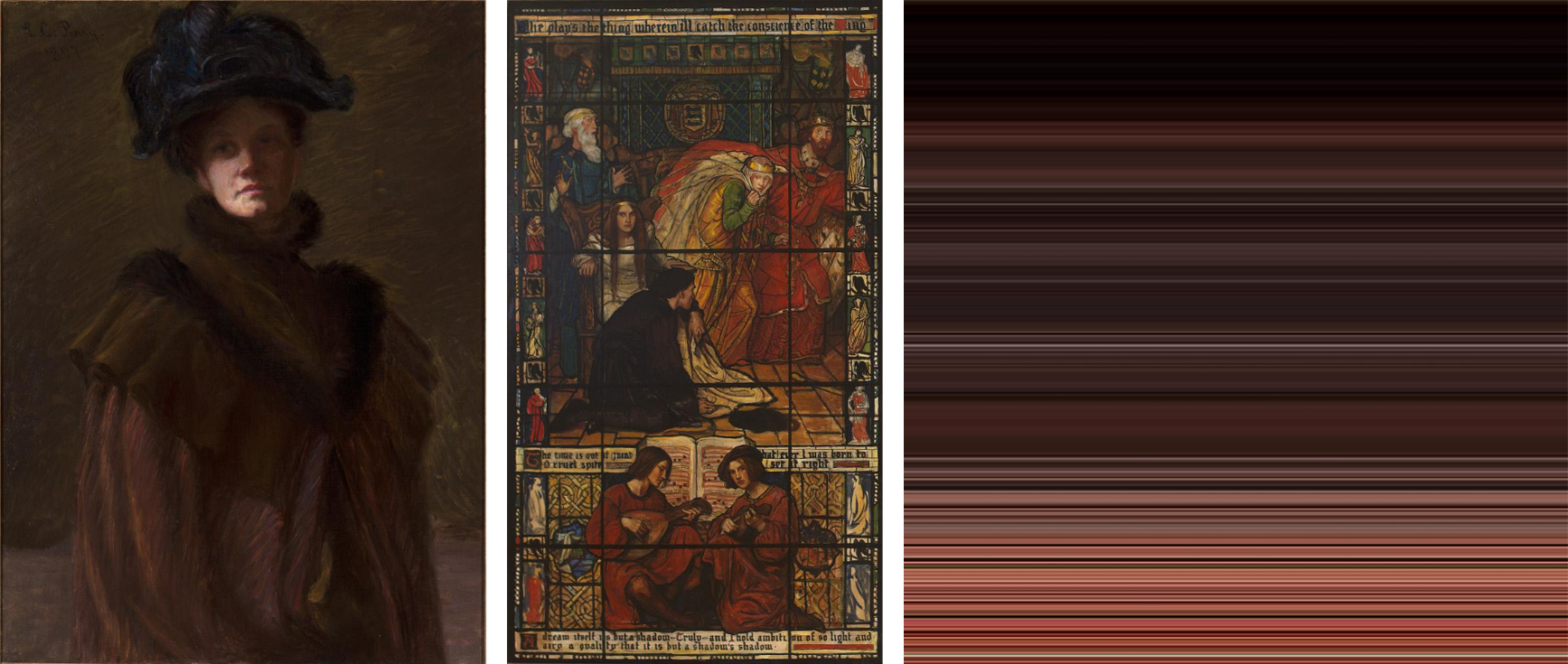

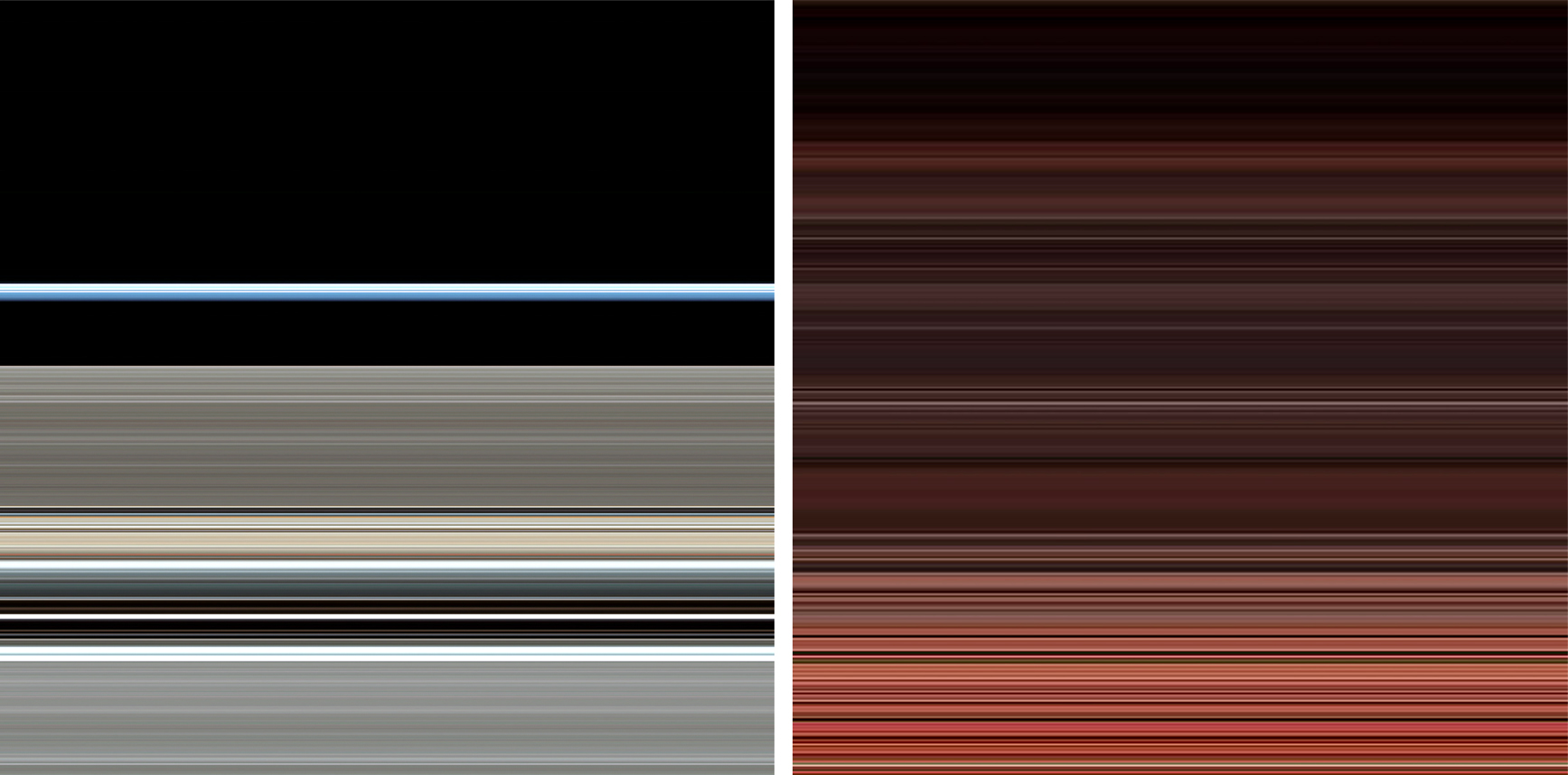

Glorious Truth (part 2) River Reporter, August 2022 (2), 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Metallic paint on newspaper, 12 13/16 × 19 7/8 inches. sheet: 13 5/8 × 20 7/8 in. (34.6 × 53 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott. Left to right: Moon_1L21, 2019 – 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Archival pigment print on aluminum, 12 × 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott. Mars_15L2B, 2021 – 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Archival pigment print on aluminum, 12 × 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott.

Left to right: Moon_1L21, 2019 – 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Archival pigment print on aluminum, 12 × 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott. Mars_15L2B, 2021 – 2022. Anna Bogatin Ott (born 1970). Archival pigment print on aluminum, 12 × 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Anna Bogatin Ott.  Portrait of Edwin Harleston (1882 – 1931). Courtesy of the College of Charleston

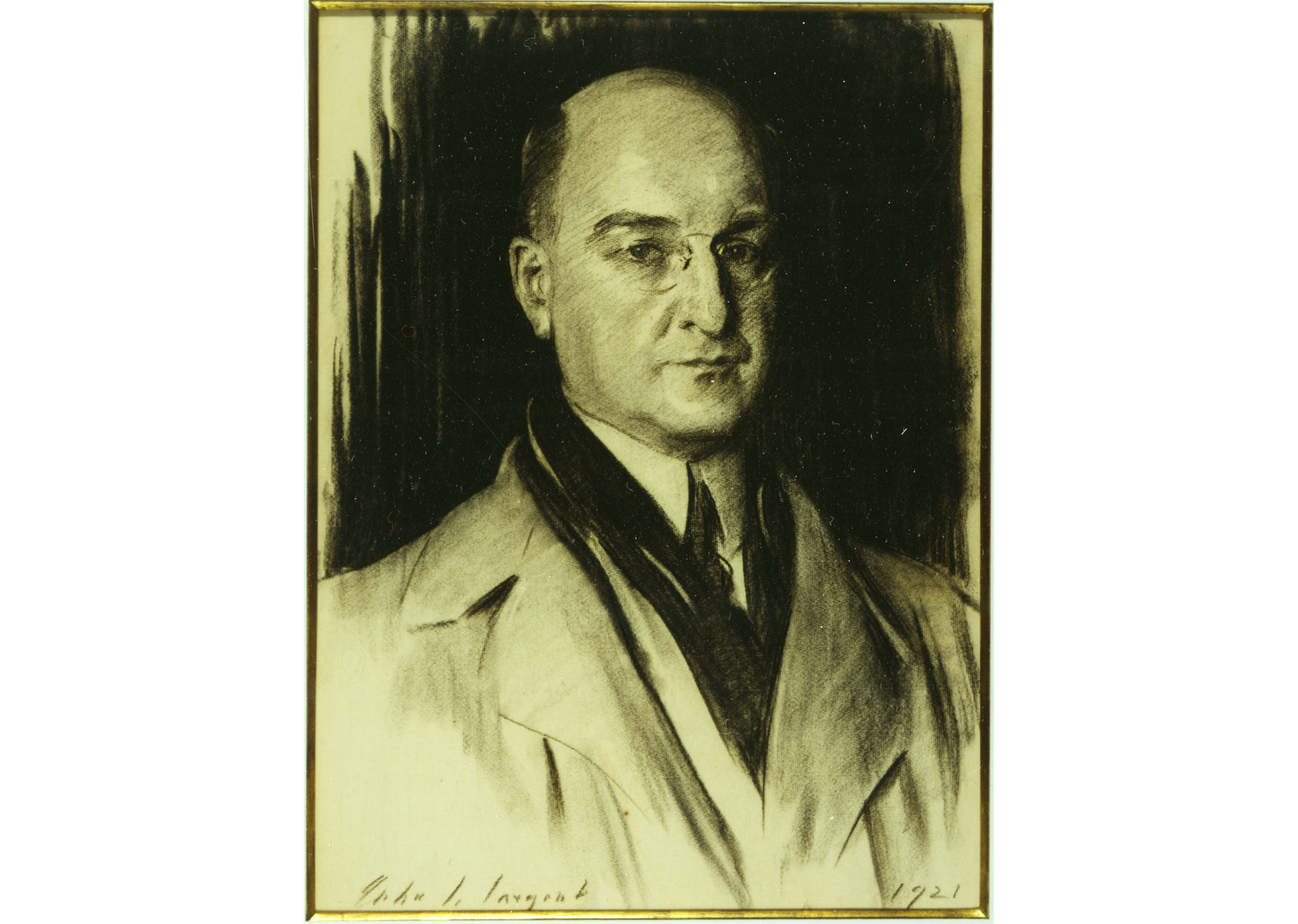

Portrait of Edwin Harleston (1882 – 1931). Courtesy of the College of Charleston John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925). Portrait of Pierre S. Dupont (1921). Image courtesy of Longwood Gardens

John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925). Portrait of Pierre S. Dupont (1921). Image courtesy of Longwood Gardens  Full length Kalmar Nyckel Mural courtesy of Michael Kalmbach.

Full length Kalmar Nyckel Mural courtesy of Michael Kalmbach.  Left to Right: Taste; Smell; Hearing; Touch; Seeing, 1911-1912. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on ivory, 3 × 2 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

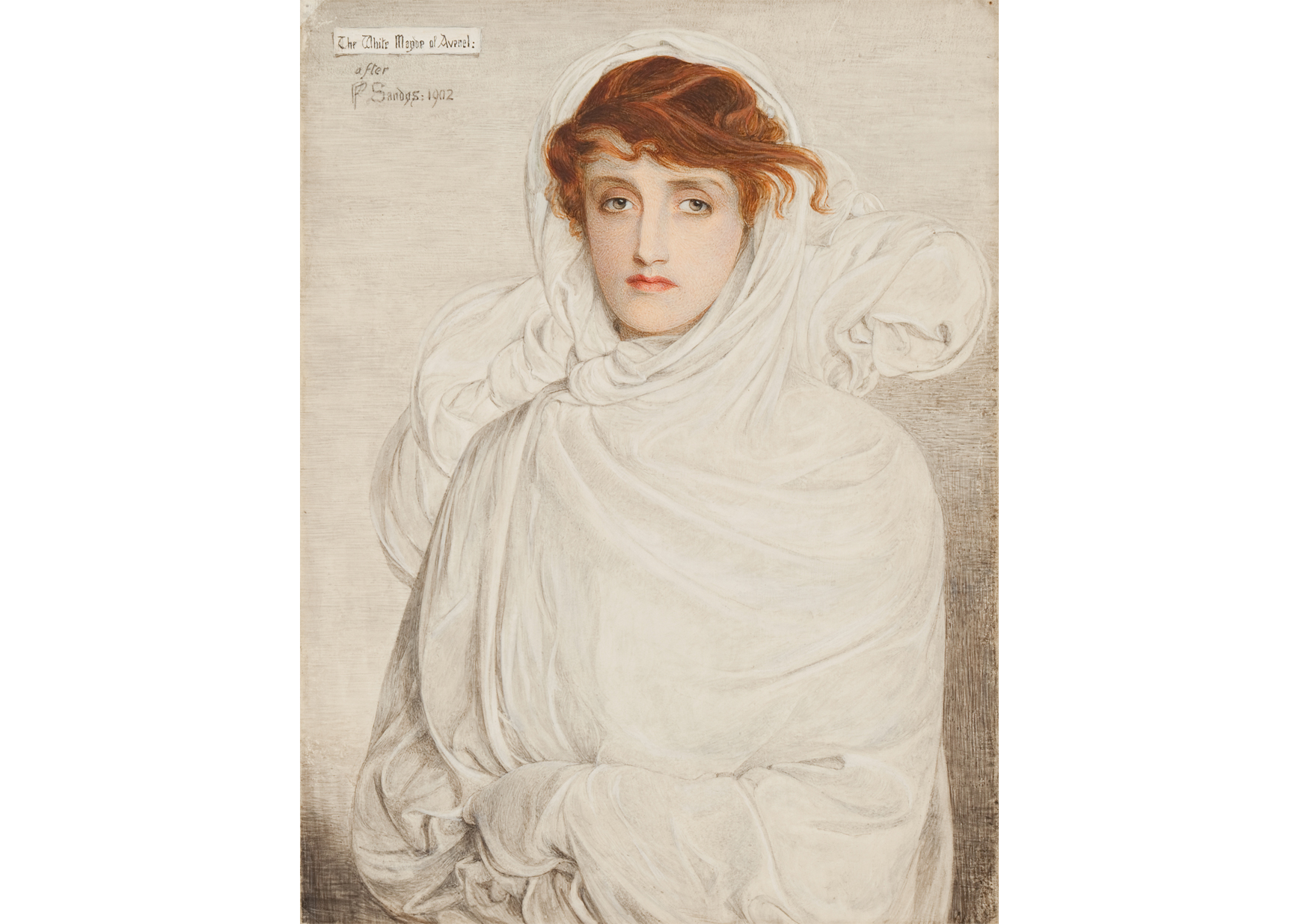

Left to Right: Taste; Smell; Hearing; Touch; Seeing, 1911-1912. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on ivory, 3 × 2 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. White Mayde of Avenel, after 1902. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on vellum, 8 × 6 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

White Mayde of Avenel, after 1902. Winifred Sandys (1875–1944). Watercolor on vellum, 8 × 6 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. Left: Apple Stem, 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, watercolor and gouache on buff paper, 9 × 7 1/2 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Right: Apple Blossom, c. 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, ink, watercolor, and gouache on buff paper, 9 9/16 x 7 11/16 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Left: Apple Stem, 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, watercolor and gouache on buff paper, 9 × 7 1/2 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

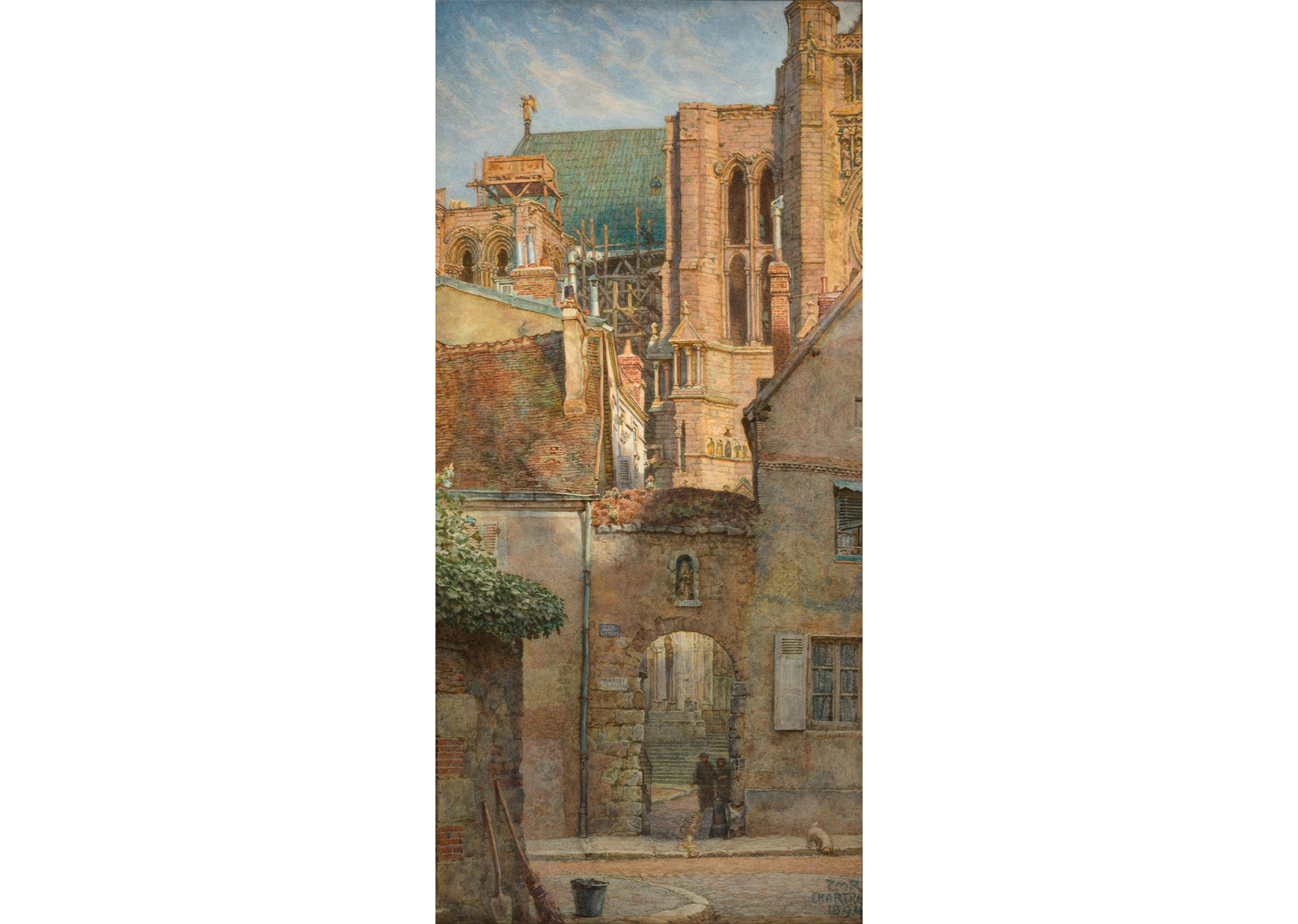

Right: Apple Blossom, c. 1878. Frederic James Shields (1833–1911). Graphite, ink, watercolor, and gouache on buff paper, 9 9/16 x 7 11/16 in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. A Gate leading to the North Transept of Chartres Cathedral, France, 1894. Thomas Matthews Rooke (1842–1942). Watercolor over graphite, 19 1/4 × 9 ¼ in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

A Gate leading to the North Transept of Chartres Cathedral, France, 1894. Thomas Matthews Rooke (1842–1942). Watercolor over graphite, 19 1/4 × 9 ¼ in. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. Anemones, 1884. Henry Roderick Newman (1843–1917). Watercolor on paper, 9 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. Paul Worman Fine Art, Worcester, MA.

Anemones, 1884. Henry Roderick Newman (1843–1917). Watercolor on paper, 9 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. Paul Worman Fine Art, Worcester, MA. Ventnor, Isle of Wight, 1856. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891). Watercolor and gouache on paper [with scratching out], 28 × 42 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2016.

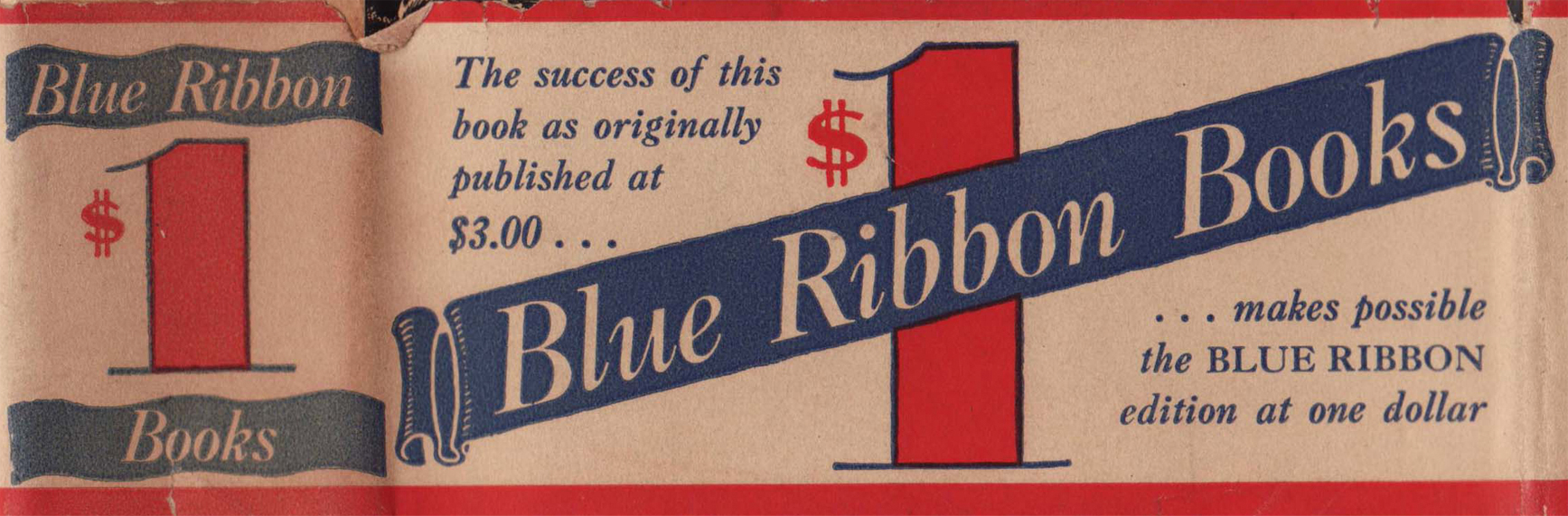

Ventnor, Isle of Wight, 1856. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891). Watercolor and gouache on paper [with scratching out], 28 × 42 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 2016. Figure 2. Promotional paper band, which originally would have been wrapped around the dust jacket

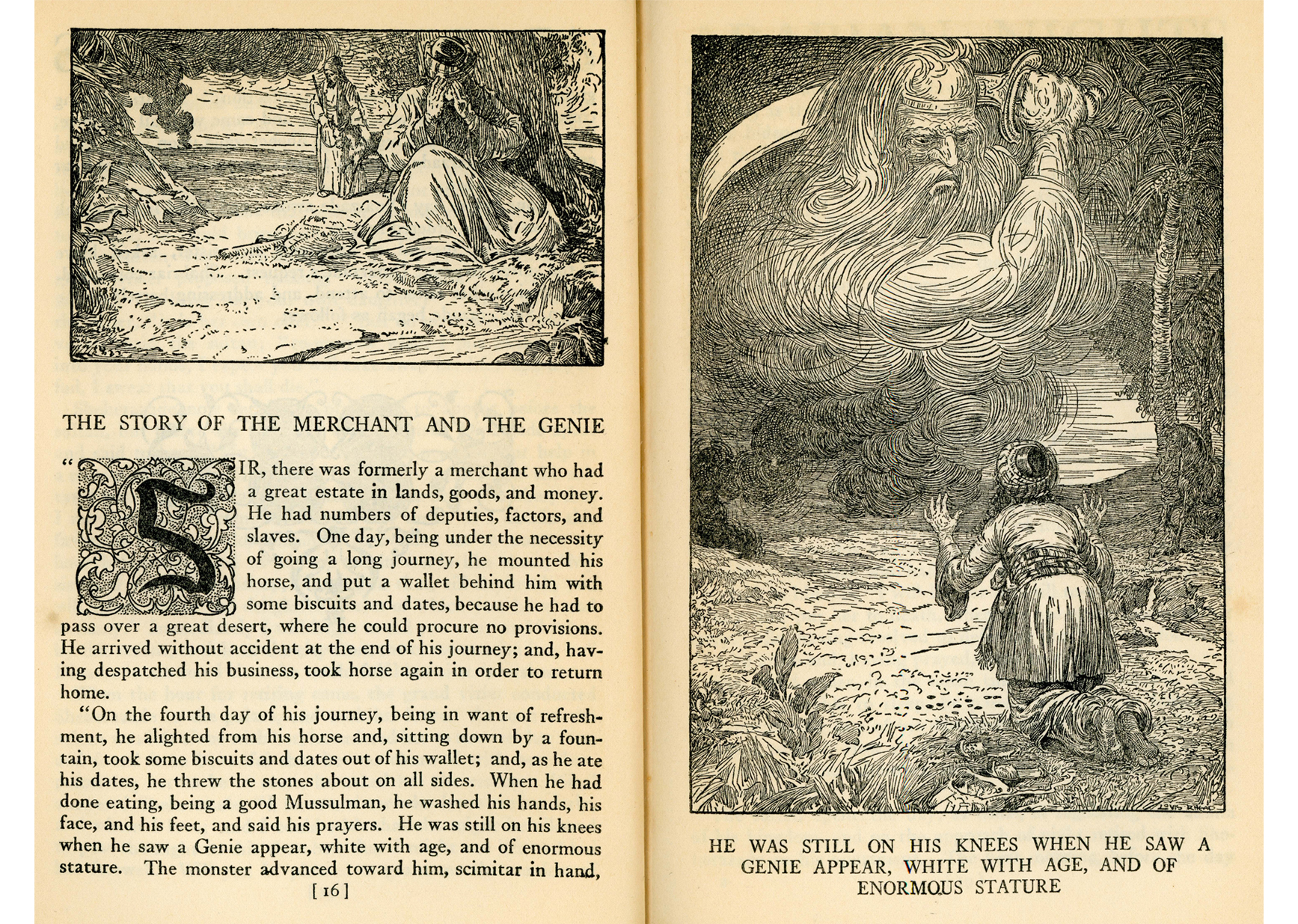

Figure 2. Promotional paper band, which originally would have been wrapped around the dust jacket Figure 3. Rhead’s illustrations from The Arabian Nights Entertainments

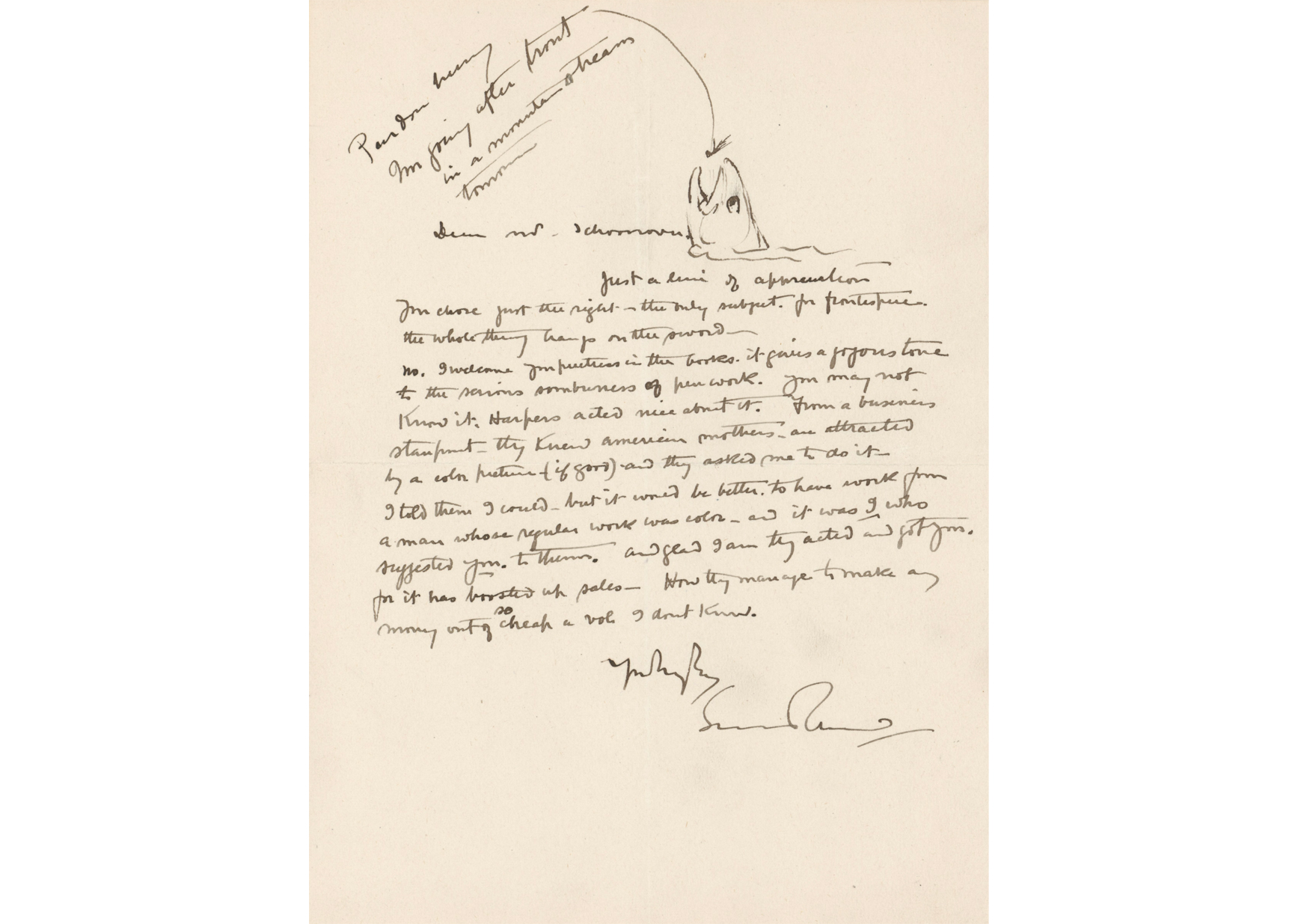

Figure 3. Rhead’s illustrations from The Arabian Nights Entertainments  Figure 4. Letter from Louis Rhead to Frank E. Schoonover, c. 1923. Frank E. Schoonover Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum

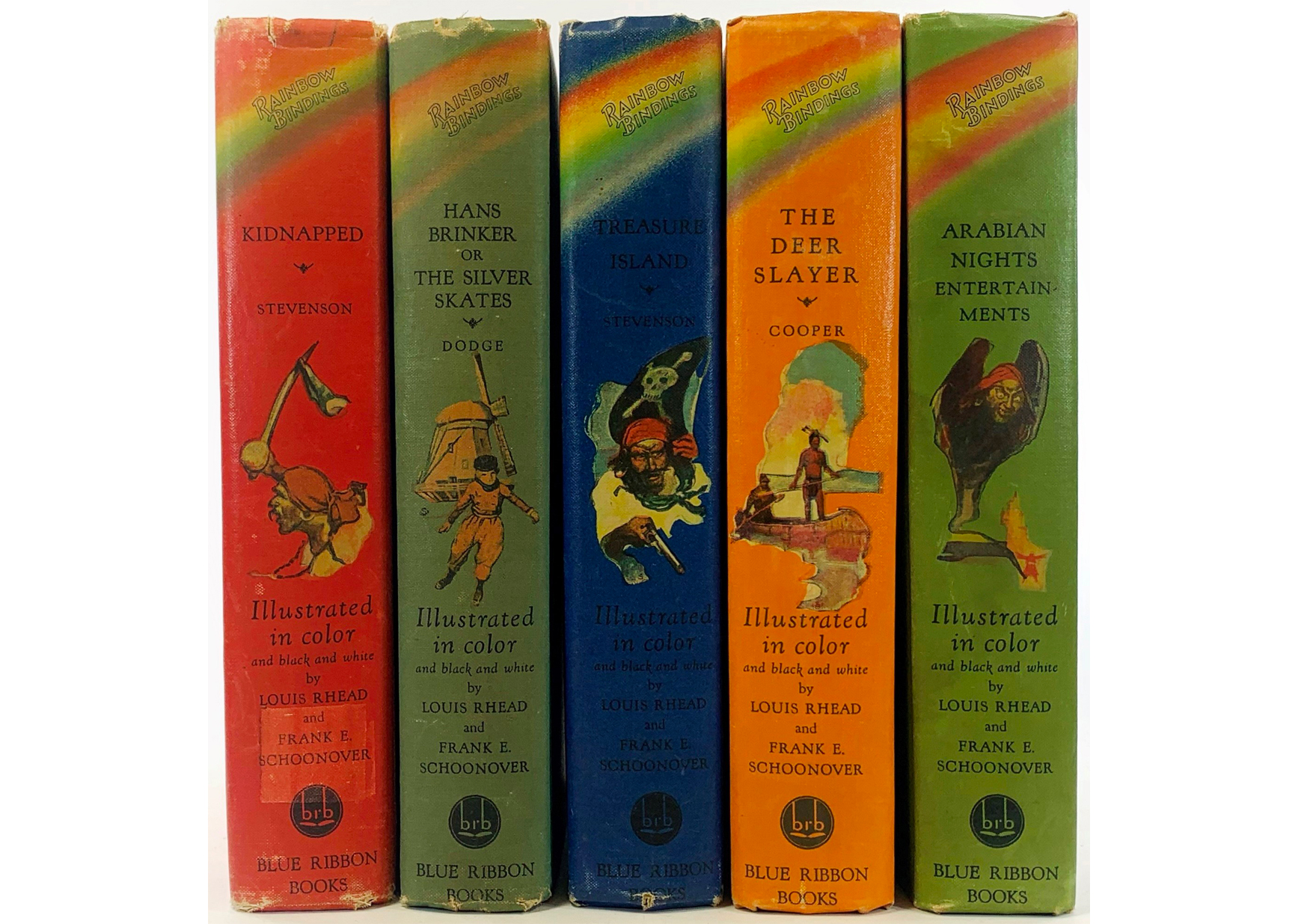

Figure 4. Letter from Louis Rhead to Frank E. Schoonover, c. 1923. Frank E. Schoonover Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Figure 5. A selection of Rainbow Bindings from the Frank E. Schoonover Library Collection showing Schoonover’s spine illustrations

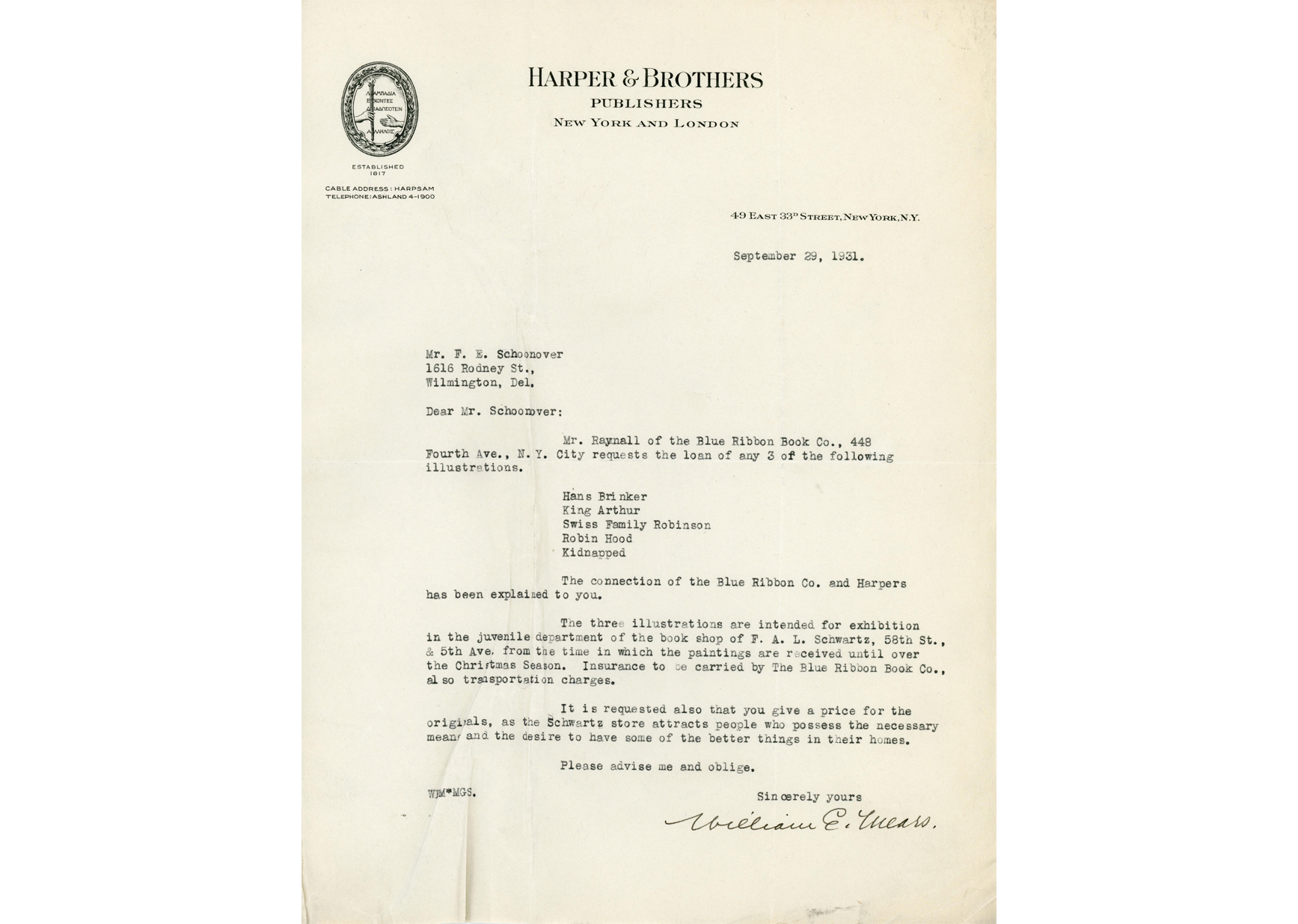

Figure 5. A selection of Rainbow Bindings from the Frank E. Schoonover Library Collection showing Schoonover’s spine illustrations Figure 6. Letter from William E. Mears, Harper & Brothers, to Frank E. Schoonover, 1931. Frank E. Schoonover Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. In this letter Mears asks Schoonover to send three of his original paintings for display in the book department of F. A. O. Schwartz over the Christmas season. He also requests a price for the originals, “as the Schwartz store attracts people who possess the necessary means and the desire to have some of the better things in their homes.” Schoonover sent five paintings for display, all of which were returned to him in early 1932.

Figure 6. Letter from William E. Mears, Harper & Brothers, to Frank E. Schoonover, 1931. Frank E. Schoonover Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. In this letter Mears asks Schoonover to send three of his original paintings for display in the book department of F. A. O. Schwartz over the Christmas season. He also requests a price for the originals, “as the Schwartz store attracts people who possess the necessary means and the desire to have some of the better things in their homes.” Schoonover sent five paintings for display, all of which were returned to him in early 1932.

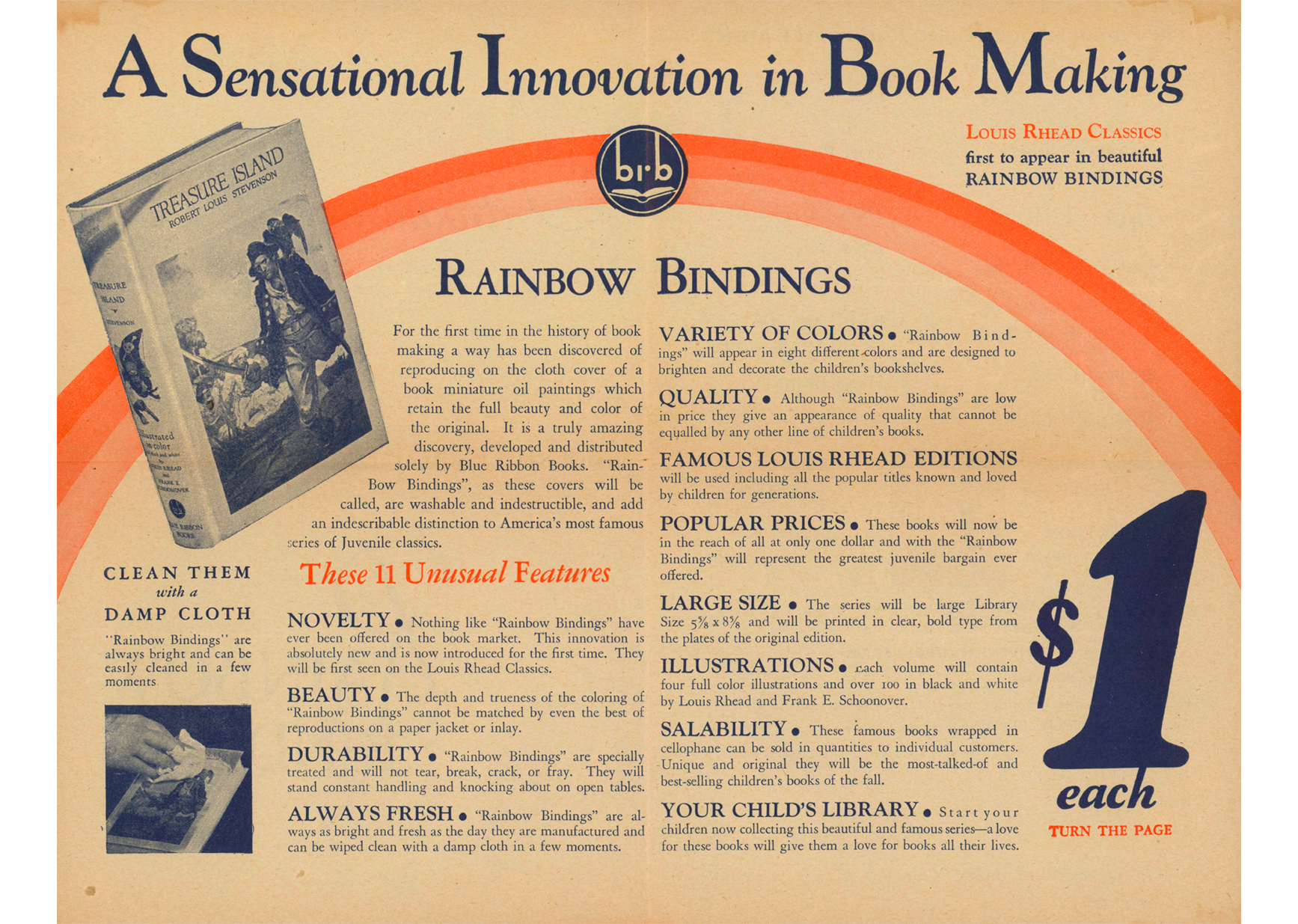

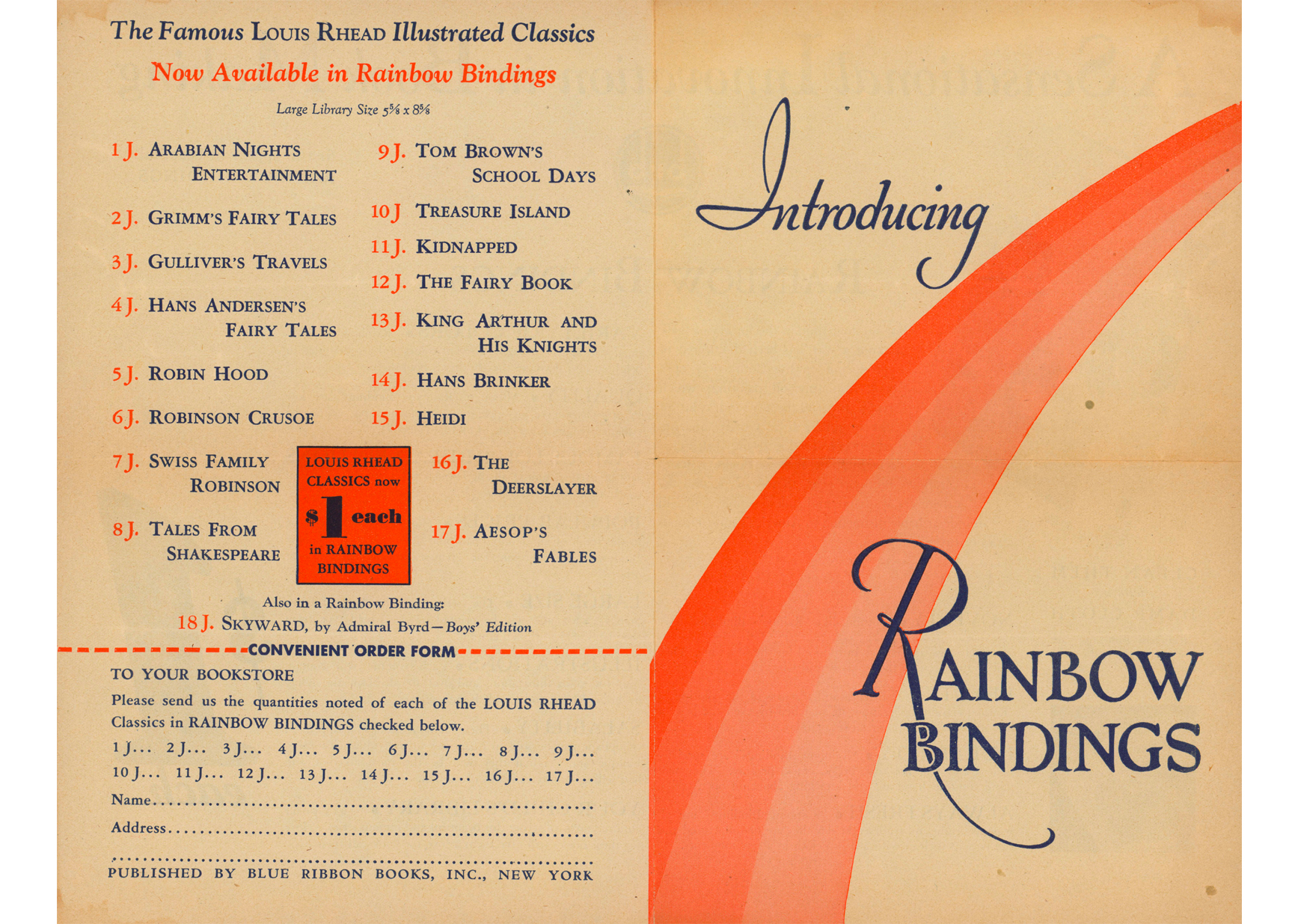

Figures 7 and 8. “Introducing Rainbow Bindings” advertising brochure. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Robert and Mary Walsh.

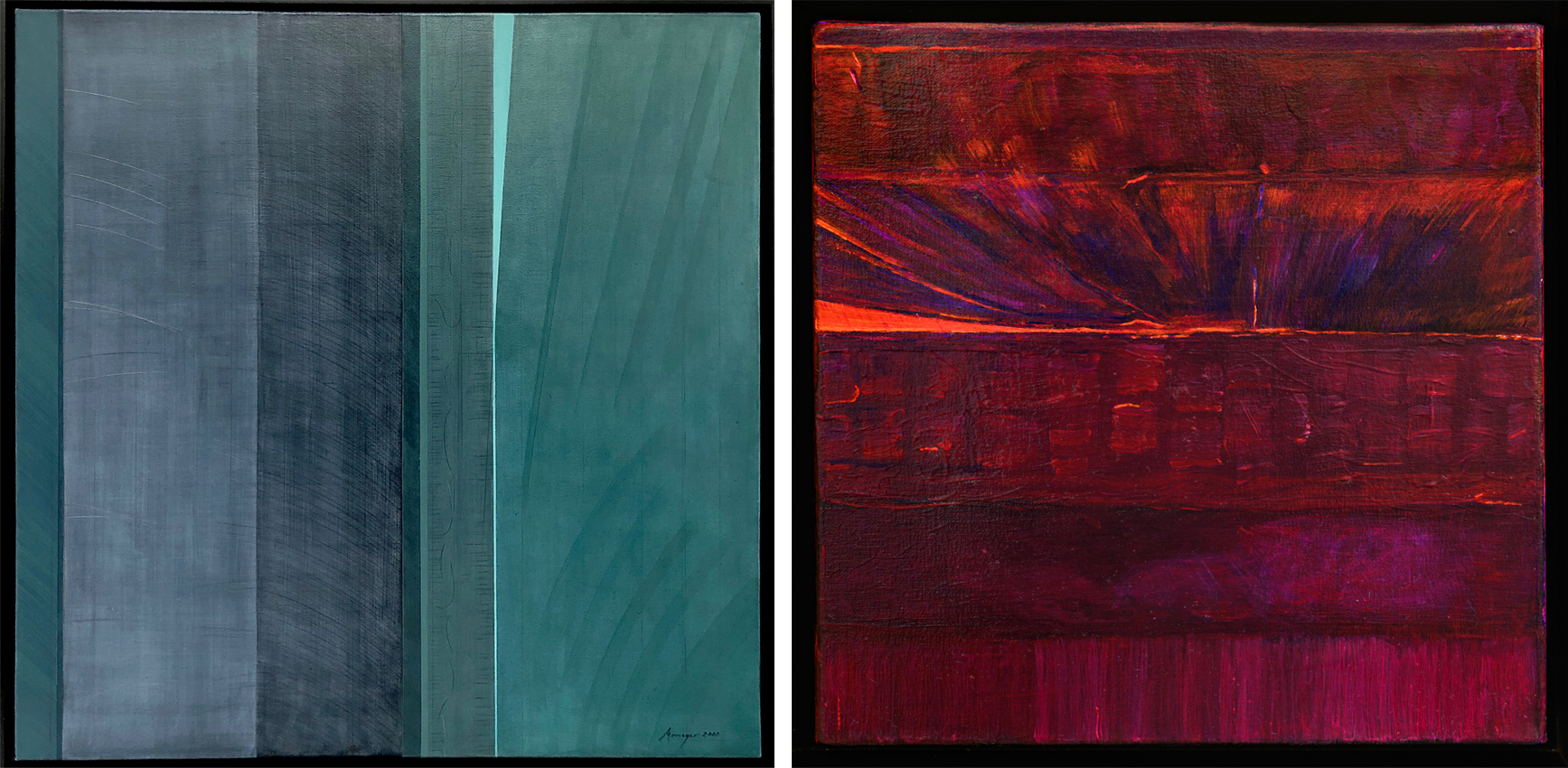

Figures 7 and 8. “Introducing Rainbow Bindings” advertising brochure. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Robert and Mary Walsh. Left to right: Square, Circles, Arcs, and Lines Together, 2019. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger. Square Dance, 1999–2000. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger.

Left to right: Square, Circles, Arcs, and Lines Together, 2019. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger. Square Dance, 1999–2000. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger. Ziptych with Solid Cylinder Plus 3 Open Cylinders, 2017. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on shaped canvas with acrylic and Plexiglas, cylinders on board, 27 7/8 x 74 x 1 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger.

Ziptych with Solid Cylinder Plus 3 Open Cylinders, 2017. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on shaped canvas with acrylic and Plexiglas, cylinders on board, 27 7/8 x 74 x 1 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger.  Left to right: Towards Disharmony II, 2003. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 inches. Collection of Kim Memeger. © Wes Memeger. Towards Harmony, 2004. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger.

Left to right: Towards Disharmony II, 2003. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 inches. Collection of Kim Memeger. © Wes Memeger. Towards Harmony, 2004. Wes Memeger (born 1939). Acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Wes Memeger.

Left to right:

Left to right:  Left to right: Hieronymus Bosch: Garden of Earthly Delights, 2015. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Welded steel assemblage with found and fabricated objects, bronze, and paint, 49 × 29 × 28 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts. | Fibonacci, 2013. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Steel and paint, 20 x 19 x 13 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts.

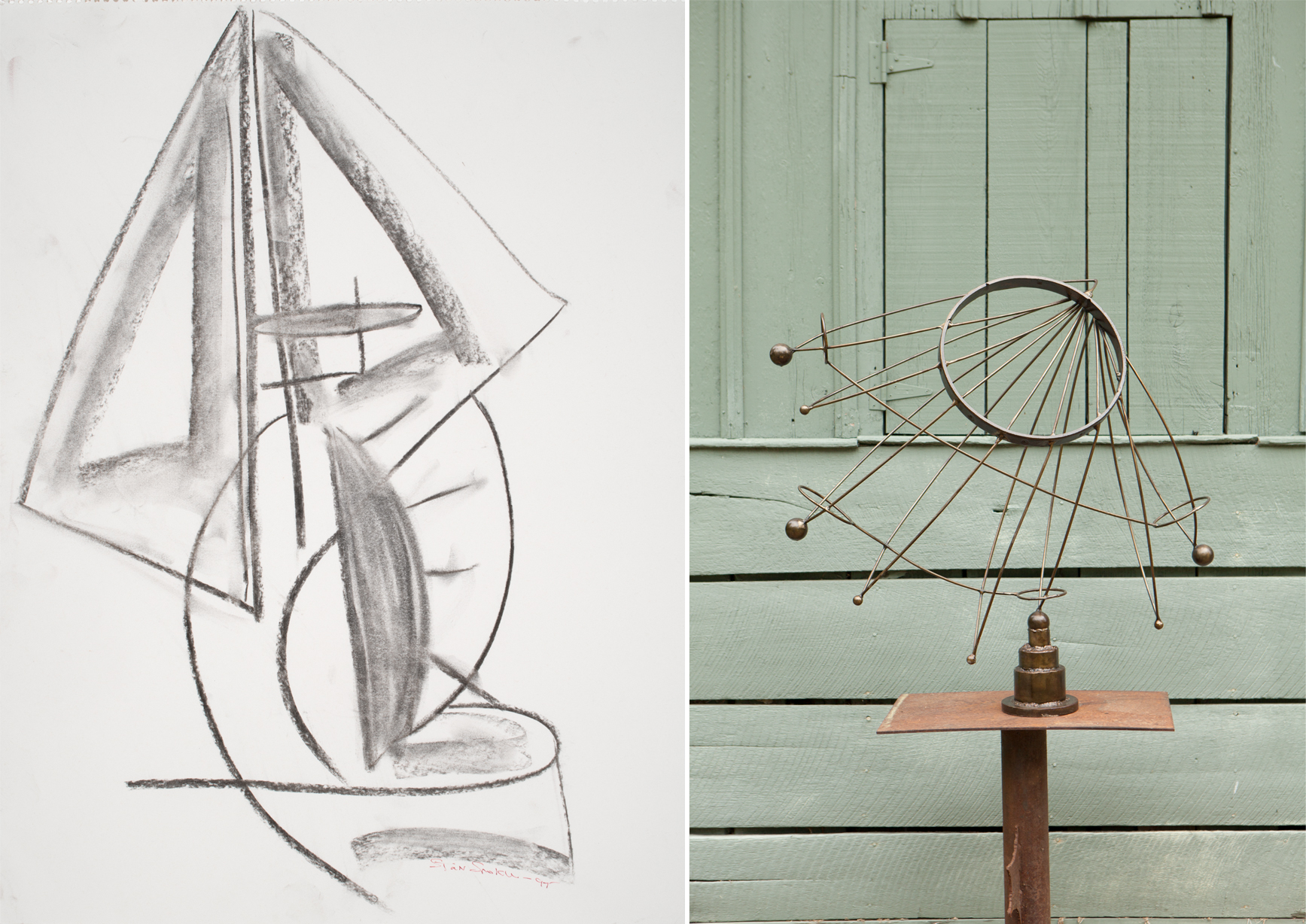

Left to right: Hieronymus Bosch: Garden of Earthly Delights, 2015. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Welded steel assemblage with found and fabricated objects, bronze, and paint, 49 × 29 × 28 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts. | Fibonacci, 2013. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Steel and paint, 20 x 19 x 13 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts. Left to right: Untitled drawing, 1997. Stan Smoker (born 1944). Charcoal on paper, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Carson Zullinger. | Hemisphere, 2009. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Steel, 37 x 38 x 18 inches. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts.

Left to right: Untitled drawing, 1997. Stan Smoker (born 1944). Charcoal on paper, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Carson Zullinger. | Hemisphere, 2009. Stan Smokler (born 1944). Steel, 37 x 38 x 18 inches. © Stan Smokler. Photograph by Terry Roberts. Left to right – Figure 2: William De Morgan, Vase with persian floral decoration, 1888-1897. Earthenware. De Morgan Foundation. Figure 3: William De Morgan, Red and gold lustre dish with winged felines, 1872-1904. Earthenware. De Morgan Foundation.

Left to right – Figure 2: William De Morgan, Vase with persian floral decoration, 1888-1897. Earthenware. De Morgan Foundation. Figure 3: William De Morgan, Red and gold lustre dish with winged felines, 1872-1904. Earthenware. De Morgan Foundation. Left to right – Figure 4: Evelyn De Morgan, Flora, 1894. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. Figure 5: Evelyn De Morgan, The Gilded Cage, c. 1900. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation.

Left to right – Figure 4: Evelyn De Morgan, Flora, 1894. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. Figure 5: Evelyn De Morgan, The Gilded Cage, c. 1900. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. Left to right – Figure 6: Evelyn De Morgan, The Worship of Mammon, 1900-1909. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. Figure 7: Evelyn De Morgan, The Red Cross, 1914-1916. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation.

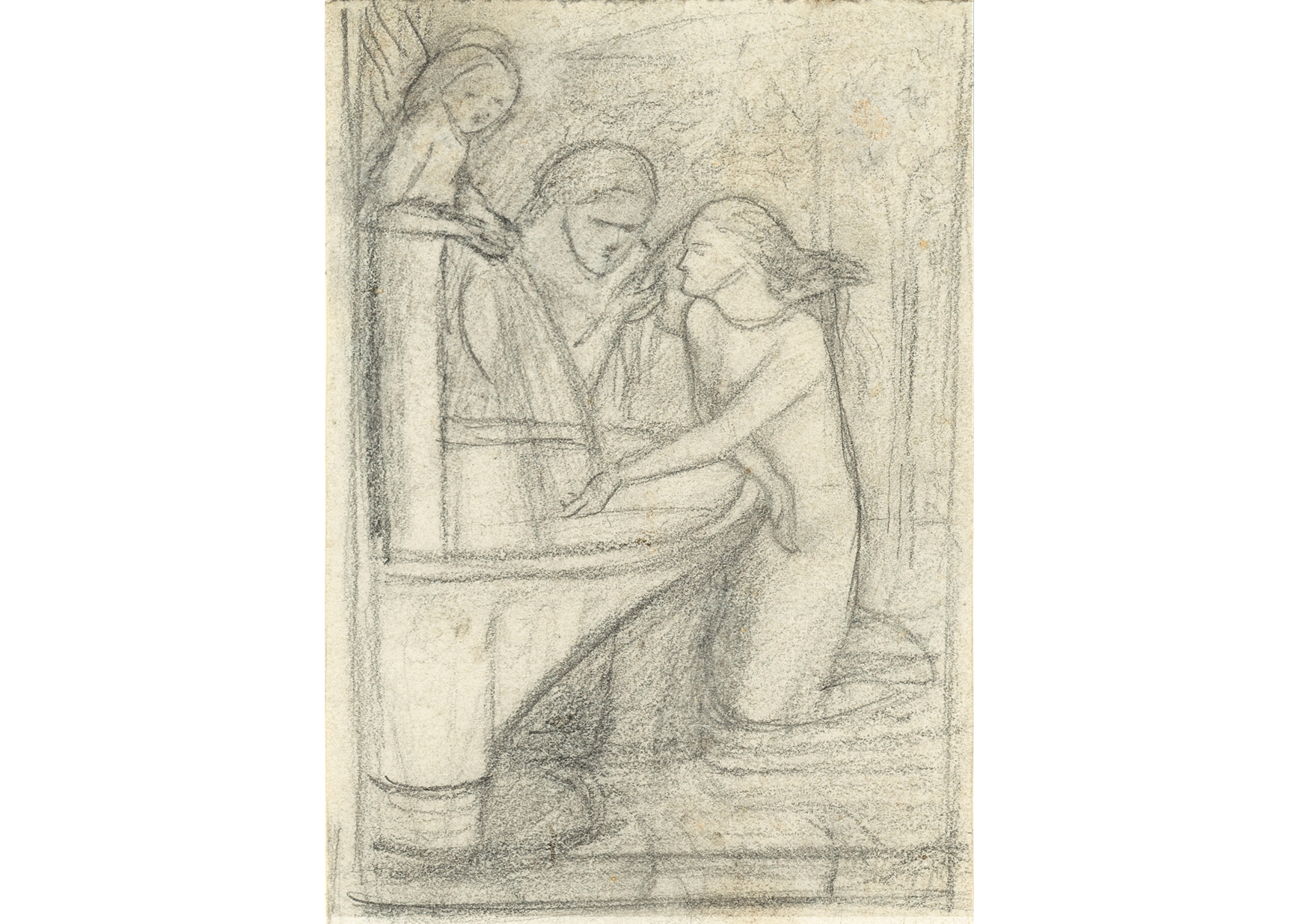

Left to right – Figure 6: Evelyn De Morgan, The Worship of Mammon, 1900-1909. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. Figure 7: Evelyn De Morgan, The Red Cross, 1914-1916. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation. ILL. #2: Sketch for ‘La Belle Dame sans merci’, c. 1855. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal (1829–1862). Graphite on paper, image: 4 1/8 × 2 7/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2007.

ILL. #2: Sketch for ‘La Belle Dame sans merci’, c. 1855. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal (1829–1862). Graphite on paper, image: 4 1/8 × 2 7/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2007. ILLs. #3 and #4: Elizabeth Siddal: ‘I Wake Again’, 2020. Holly Trostle Brigham (born 1965). Painted and velvet lined wooden box with metal hinges; leather book with lithography, screen print, hair, and hand dyed paper; dried pigment in apothecary bottle and book pages, 10 1/4 × 13 × 3 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Holly Trostle Brigham.

ILLs. #3 and #4: Elizabeth Siddal: ‘I Wake Again’, 2020. Holly Trostle Brigham (born 1965). Painted and velvet lined wooden box with metal hinges; leather book with lithography, screen print, hair, and hand dyed paper; dried pigment in apothecary bottle and book pages, 10 1/4 × 13 × 3 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Holly Trostle Brigham. Left to right: I AM (Queen), 2021. Charles Edward Williams (born 1984). Oil on mylar with etched glass, 36 1/2 x 25 3/4 inches. Commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum; Acquisition Fund, 2021. © Charles Edward Williams. | Wish You Were Here #2, 2021. Charles Edward Williams (born 1984). Oil, fishing line on watercolor paper, 5 x 7 inches. Commissioned

by the Delaware Art Museum. Courtesy of the artist. © Charles Edward Williams.

Left to right: I AM (Queen), 2021. Charles Edward Williams (born 1984). Oil on mylar with etched glass, 36 1/2 x 25 3/4 inches. Commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum; Acquisition Fund, 2021. © Charles Edward Williams. | Wish You Were Here #2, 2021. Charles Edward Williams (born 1984). Oil, fishing line on watercolor paper, 5 x 7 inches. Commissioned

by the Delaware Art Museum. Courtesy of the artist. © Charles Edward Williams. Photograph by Mitchell Kearney.

Photograph by Mitchell Kearney. Left to right: Wigwam Stories told by North American Indians, by Mary Catherine Judd (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1901), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. | Yellow Star, by Elaine Goodale Eastman (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1911), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. | The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

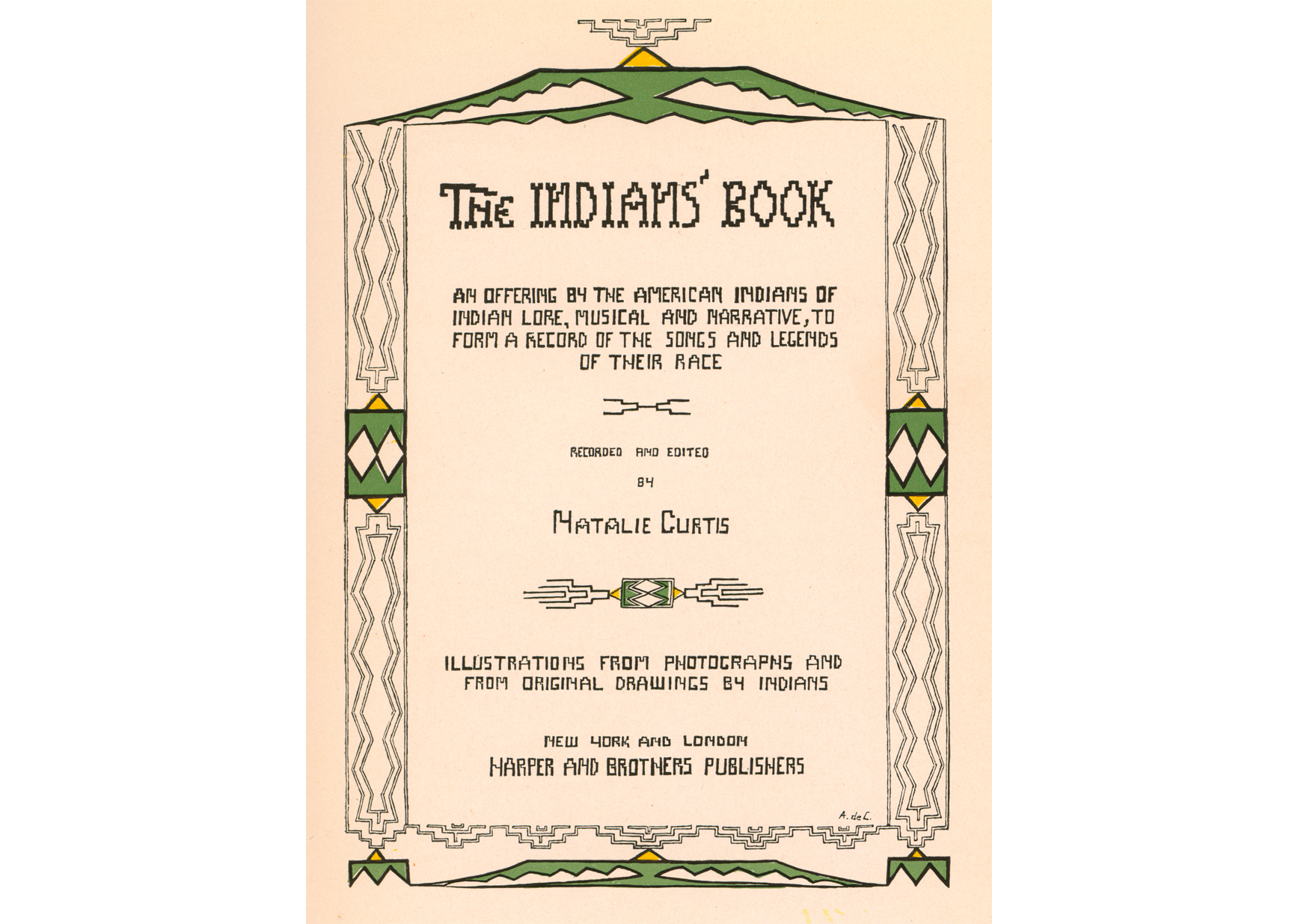

Left to right: Wigwam Stories told by North American Indians, by Mary Catherine Judd (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1901), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. | Yellow Star, by Elaine Goodale Eastman (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1911), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. | The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923), Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Title page for The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923). Angel De Cora (c. 1868-1919). Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

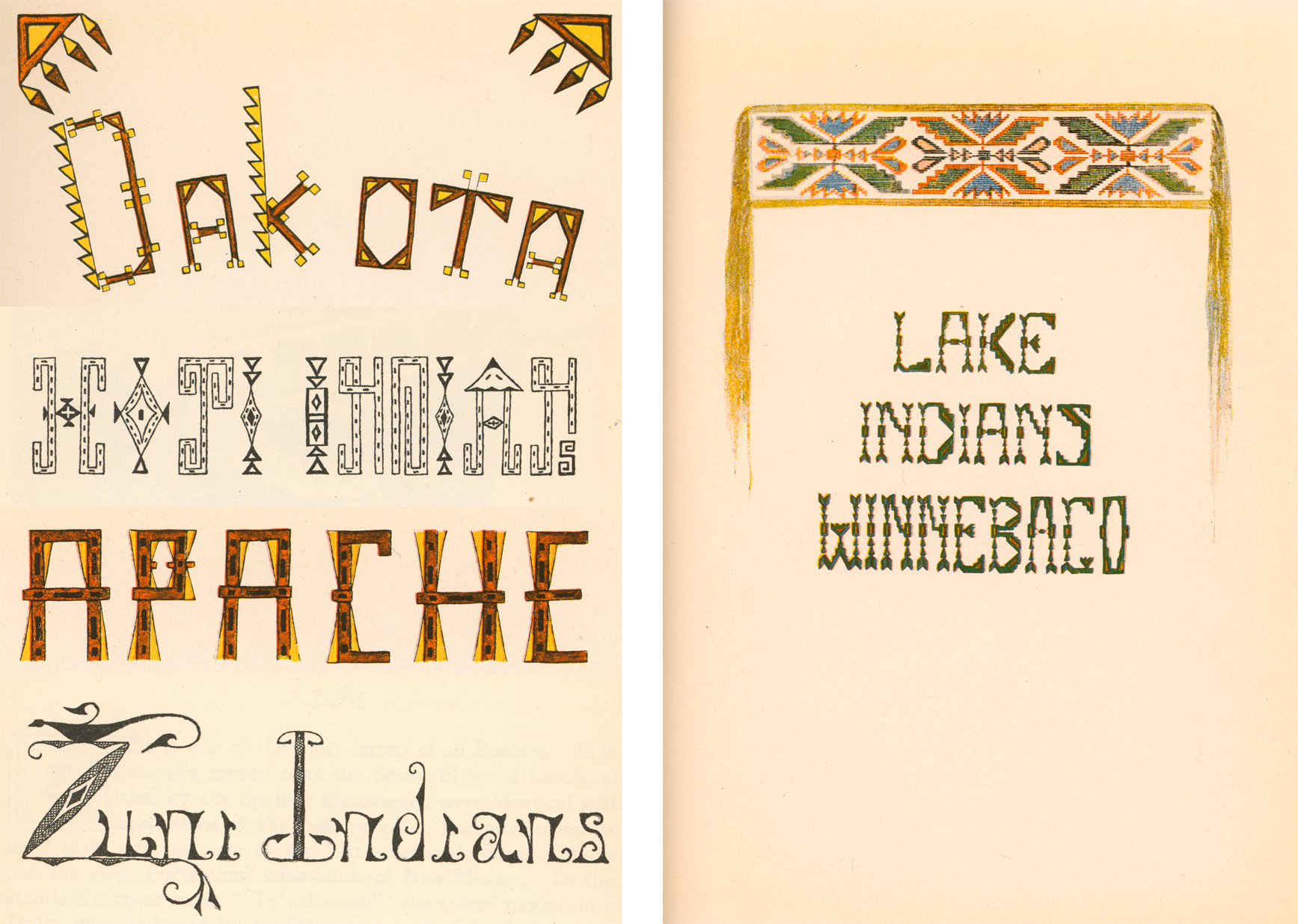

Title page for The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923). Angel De Cora (c. 1868-1919). Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Chapter title page lettering for The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923). Angel De Cora (c. 1868-1919). Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

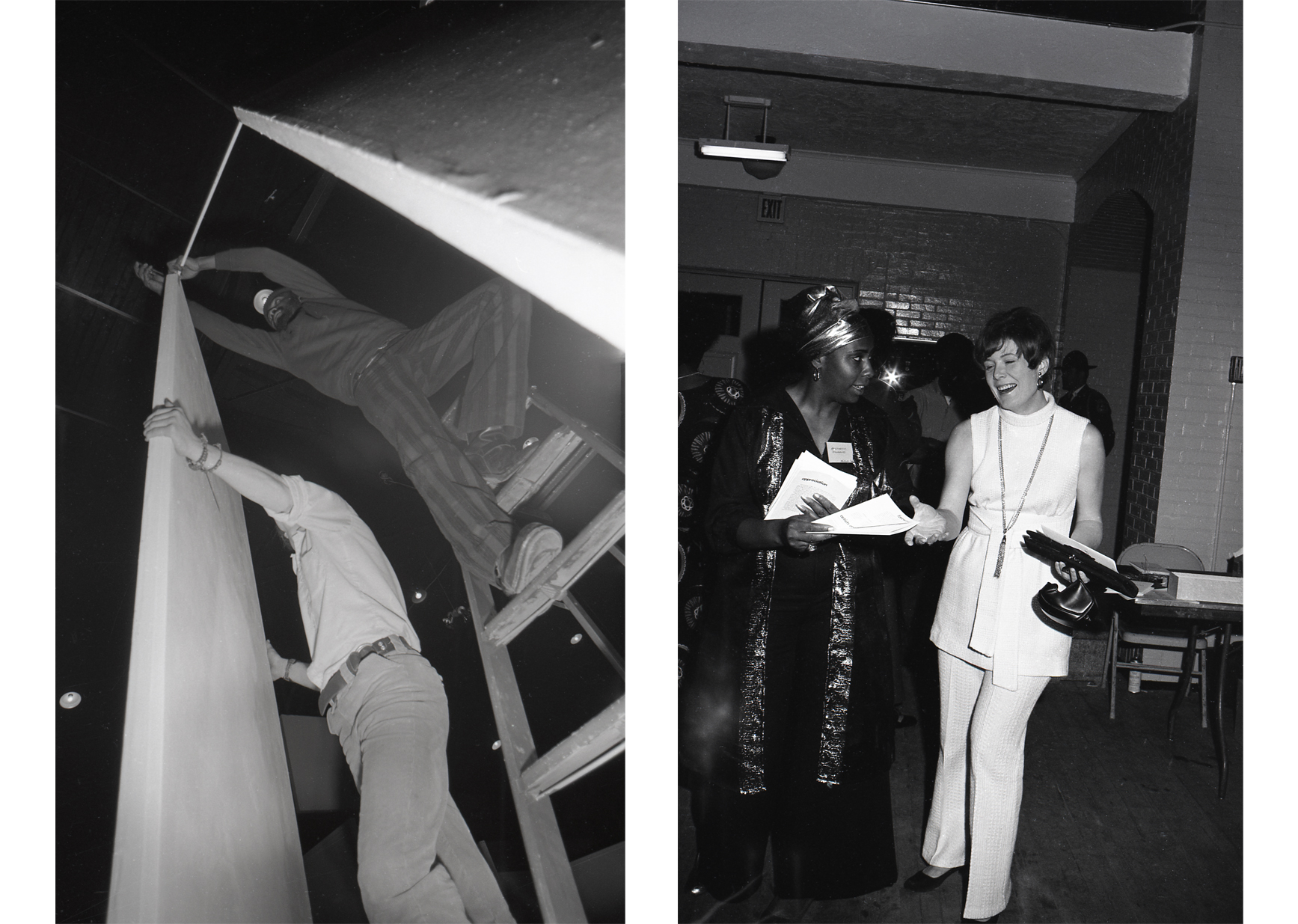

Chapter title page lettering for The Indians’ Book, by Natalie Curtis (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1923). Angel De Cora (c. 1868-1919). Special Collections, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Left to right: Photograph of Simmie Knox (center) during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). | Photograph of Gertrude Redden Jenkins (left) and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Left to right: Photograph of Simmie Knox (center) during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). | Photograph of Gertrude Redden Jenkins (left) and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).  Photograph of Carol Shrier Reed during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of Carol Shrier Reed during Afro-American Images 1971 installation, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). Photograph of (left to right) Delilah W. Pierce, Alma Thomas, and Dorothy Porter with Larry Erskine Thomas’ Africa—The Source during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

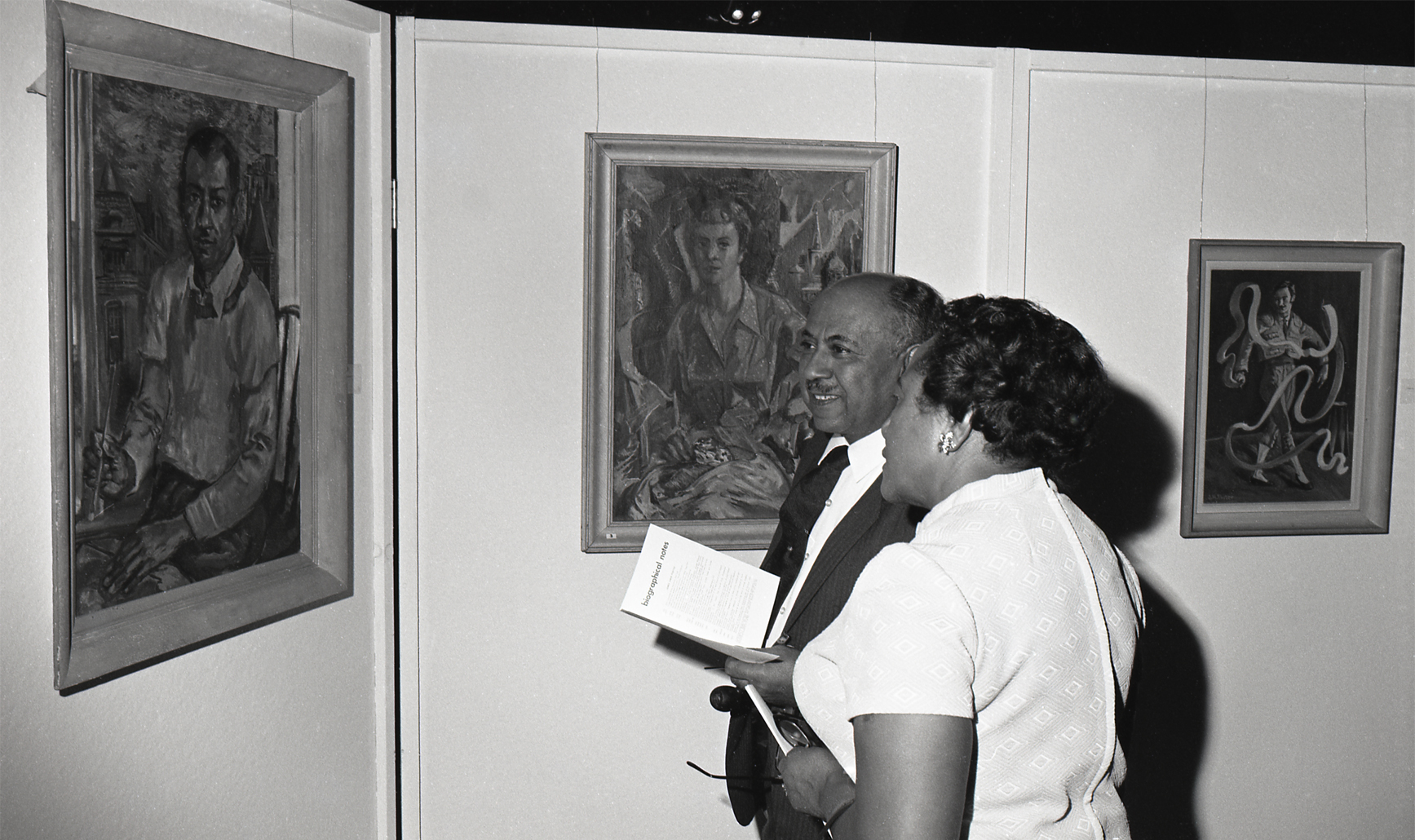

Photograph of (left to right) Delilah W. Pierce, Alma Thomas, and Dorothy Porter with Larry Erskine Thomas’ Africa—The Source during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).  Photograph of Dr. Albert J. Carter and guest with James A. Porter’s Self-Portrait (1957), Shattered Mirror (1955), and Spanish Man with Ribbon (date unknown) during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

Photograph of Dr. Albert J. Carter and guest with James A. Porter’s Self-Portrait (1957), Shattered Mirror (1955), and Spanish Man with Ribbon (date unknown) during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). Photograph of (left to right) Loïs Mailou Jones, Dr. Albert J. Carter, Delilah W. Pierce, and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

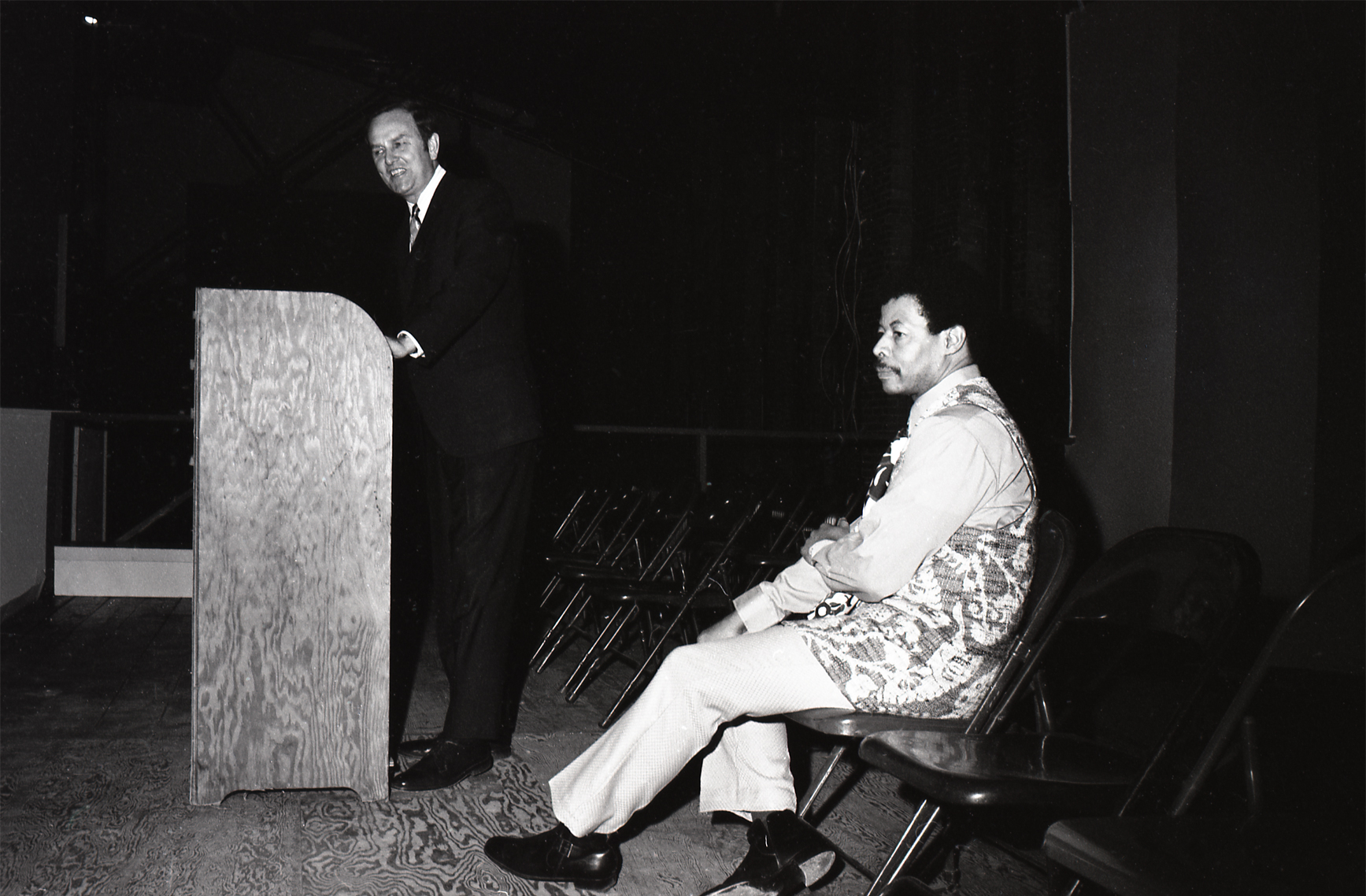

Photograph of (left to right) Loïs Mailou Jones, Dr. Albert J. Carter, Delilah W. Pierce, and others during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). Photograph of Governor Russell W. Peterson and Percy Eugene Ricks during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter).

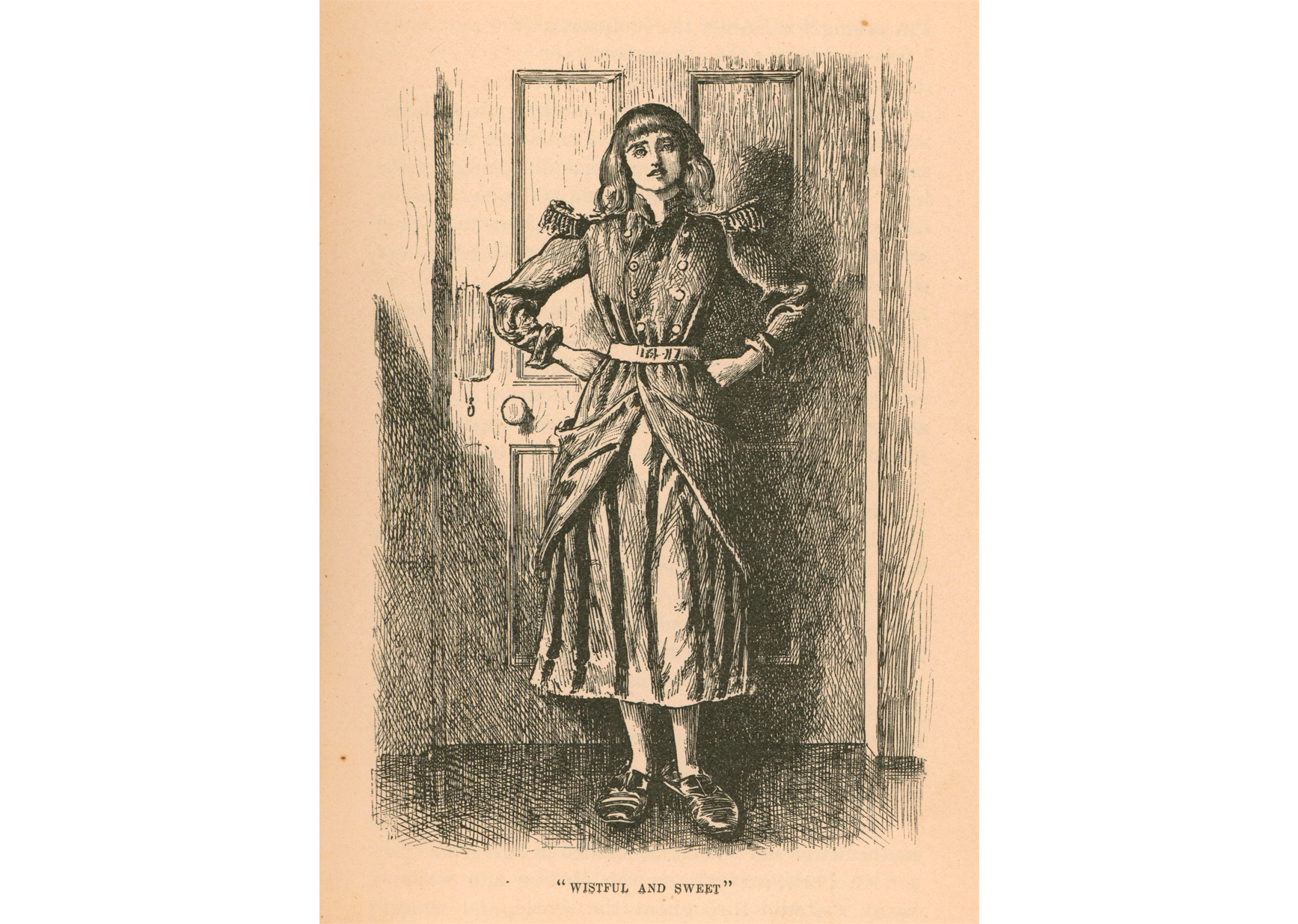

Photograph of Governor Russell W. Peterson and Percy Eugene Ricks during Afro-American Images 1971 opening, Wilmington Armory, Delaware, 1971. Photograph by Photographers Collaborative (Woldemar Shock and Richard Carter). Wistful and sweet, from Trilby, by George du Maurier (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

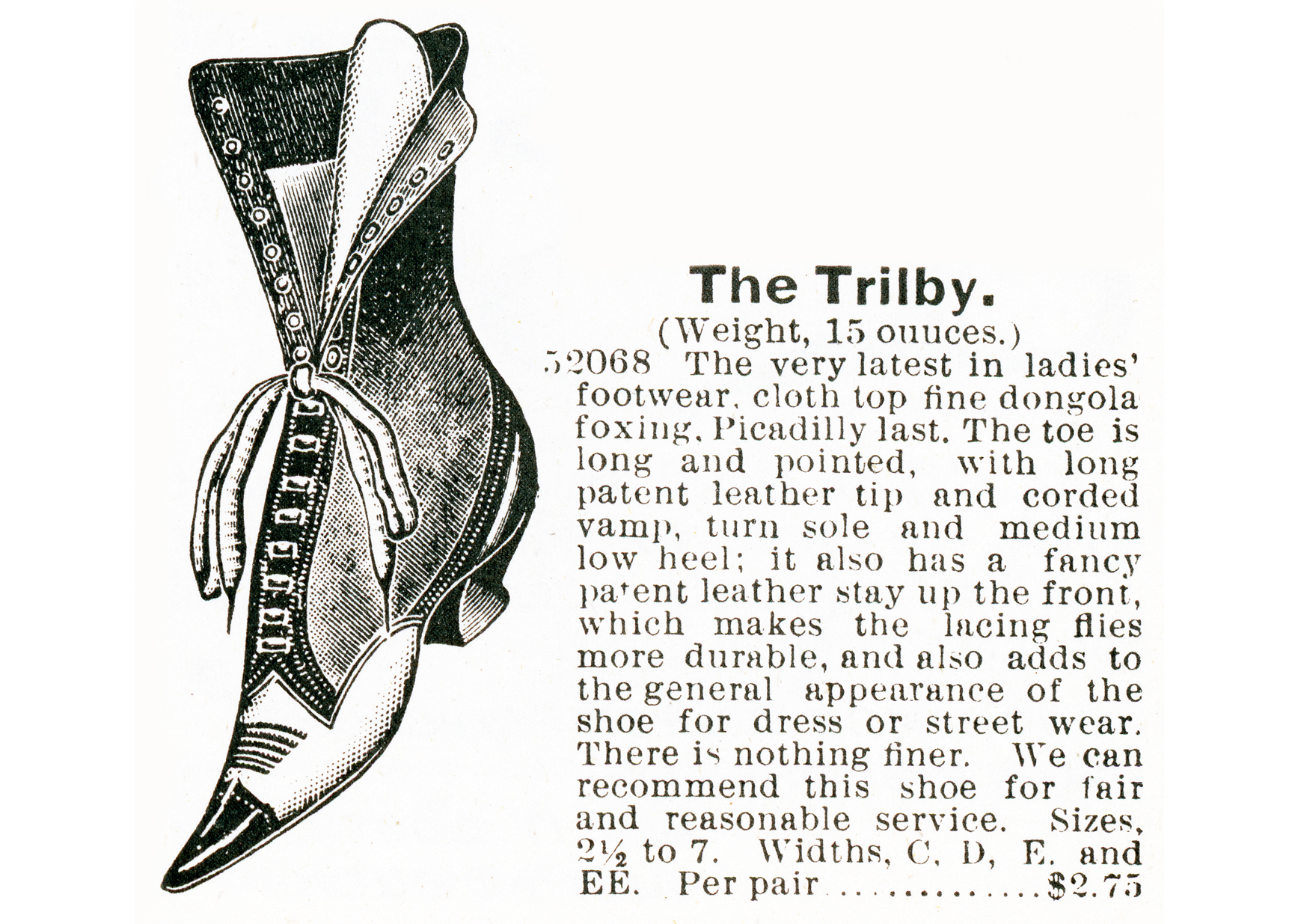

Wistful and sweet, from Trilby, by George du Maurier (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Advertisement for The Trilby from the Montgomery Ward & Company Catalogue & Buyers’ Guide, 1895. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

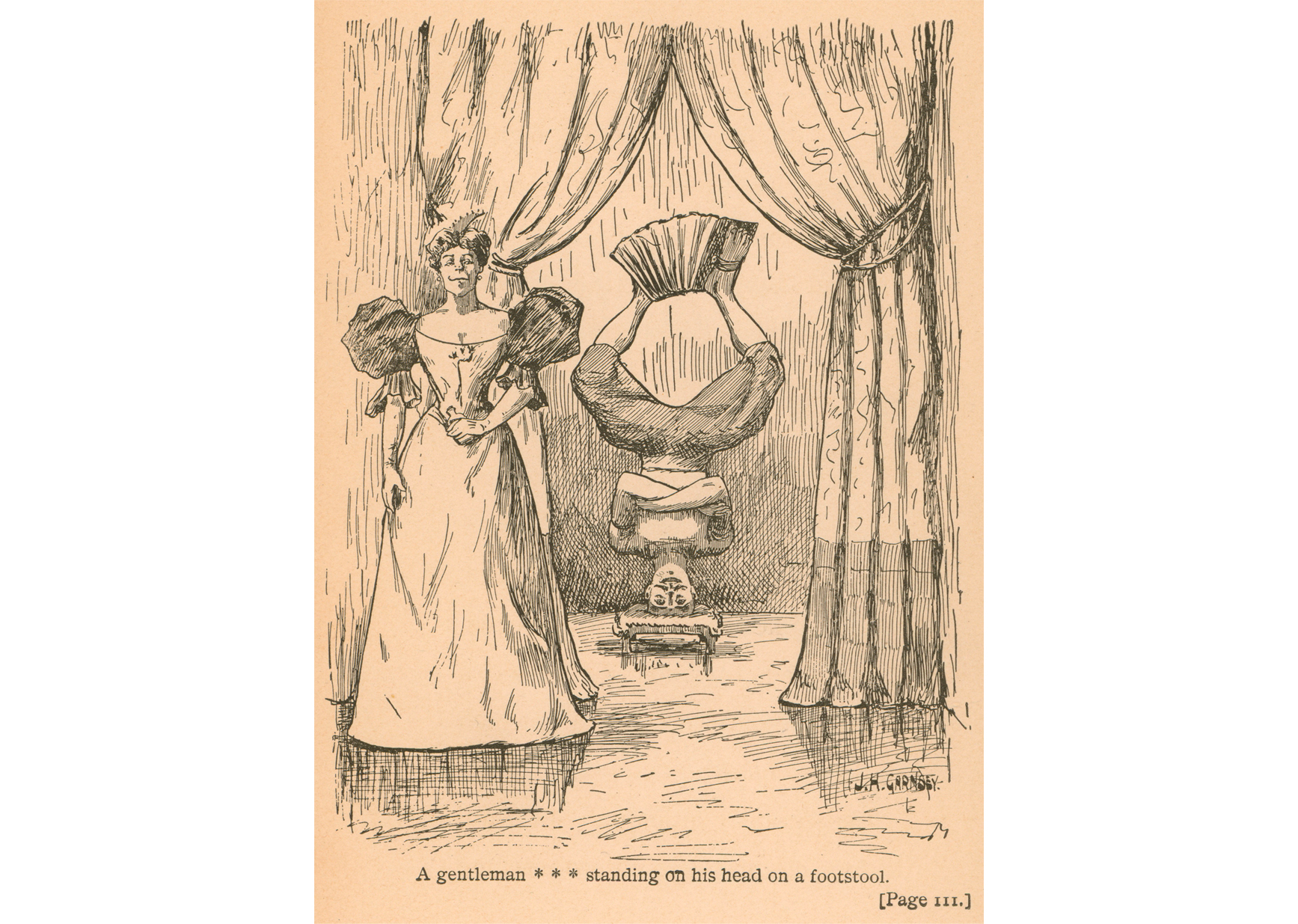

Advertisement for The Trilby from the Montgomery Ward & Company Catalogue & Buyers’ Guide, 1895. Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. A gentleman . . . standing on his head on a footstool, from Billtry, by Mary Kyle Dallas (New York: The Merriam Company, 1895). Carol Jording Rare Book Acquisition Fund, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

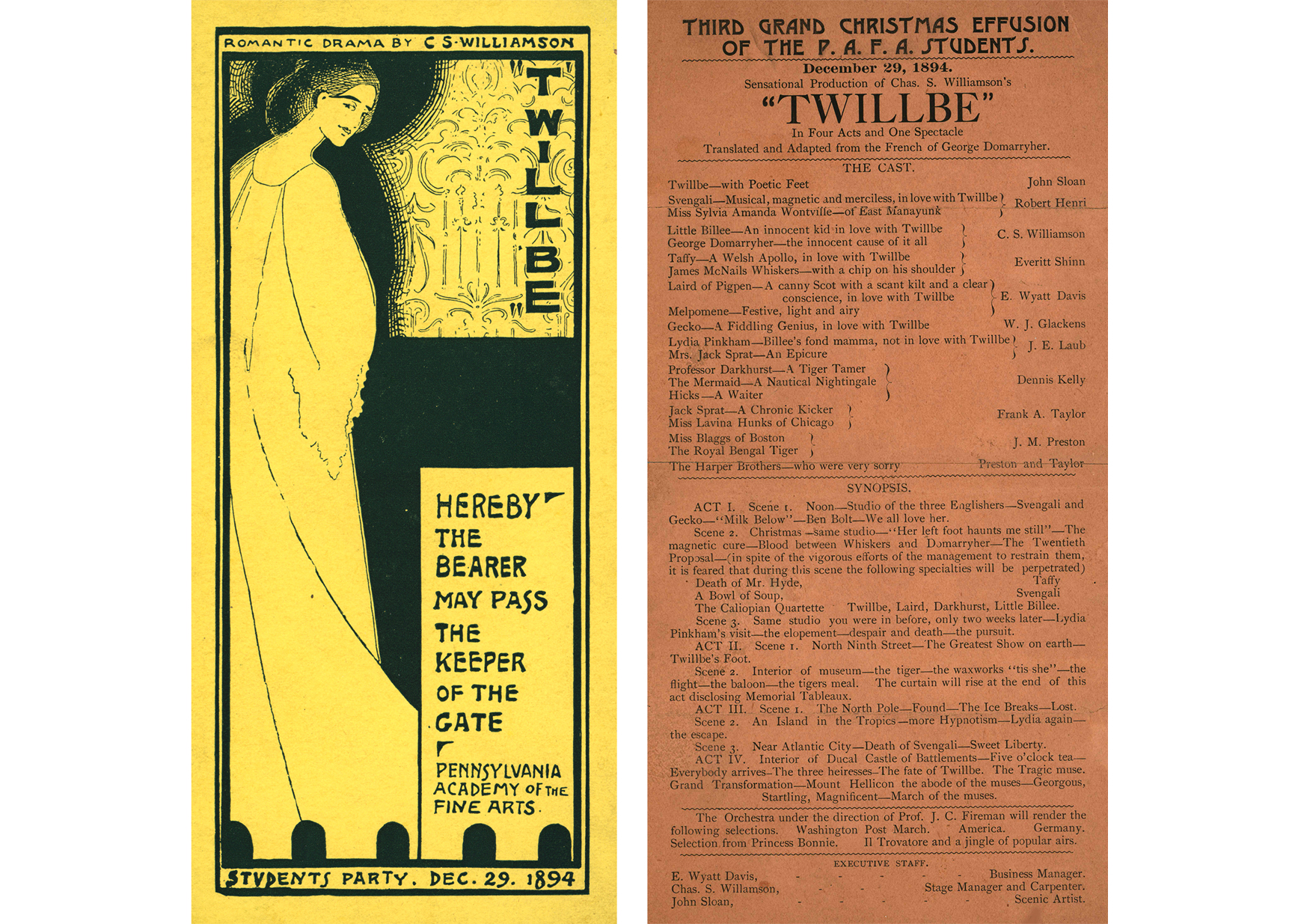

A gentleman . . . standing on his head on a footstool, from Billtry, by Mary Kyle Dallas (New York: The Merriam Company, 1895). Carol Jording Rare Book Acquisition Fund, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Ticket and playbill for the performance of Twillbe at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, December 1894. John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

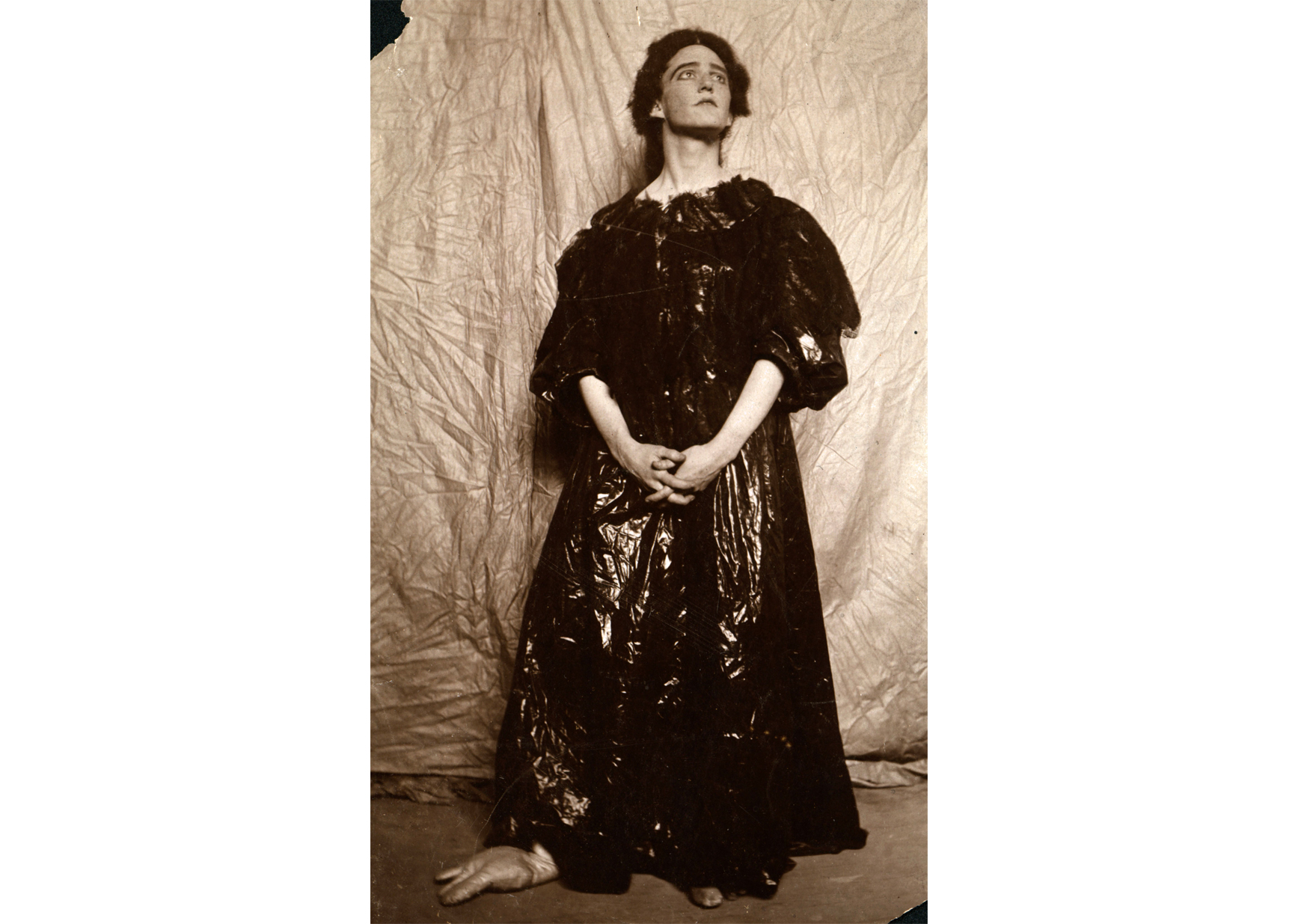

Ticket and playbill for the performance of Twillbe at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, December 1894. John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Photograph of John Sloan as Twillbe, 1894. John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

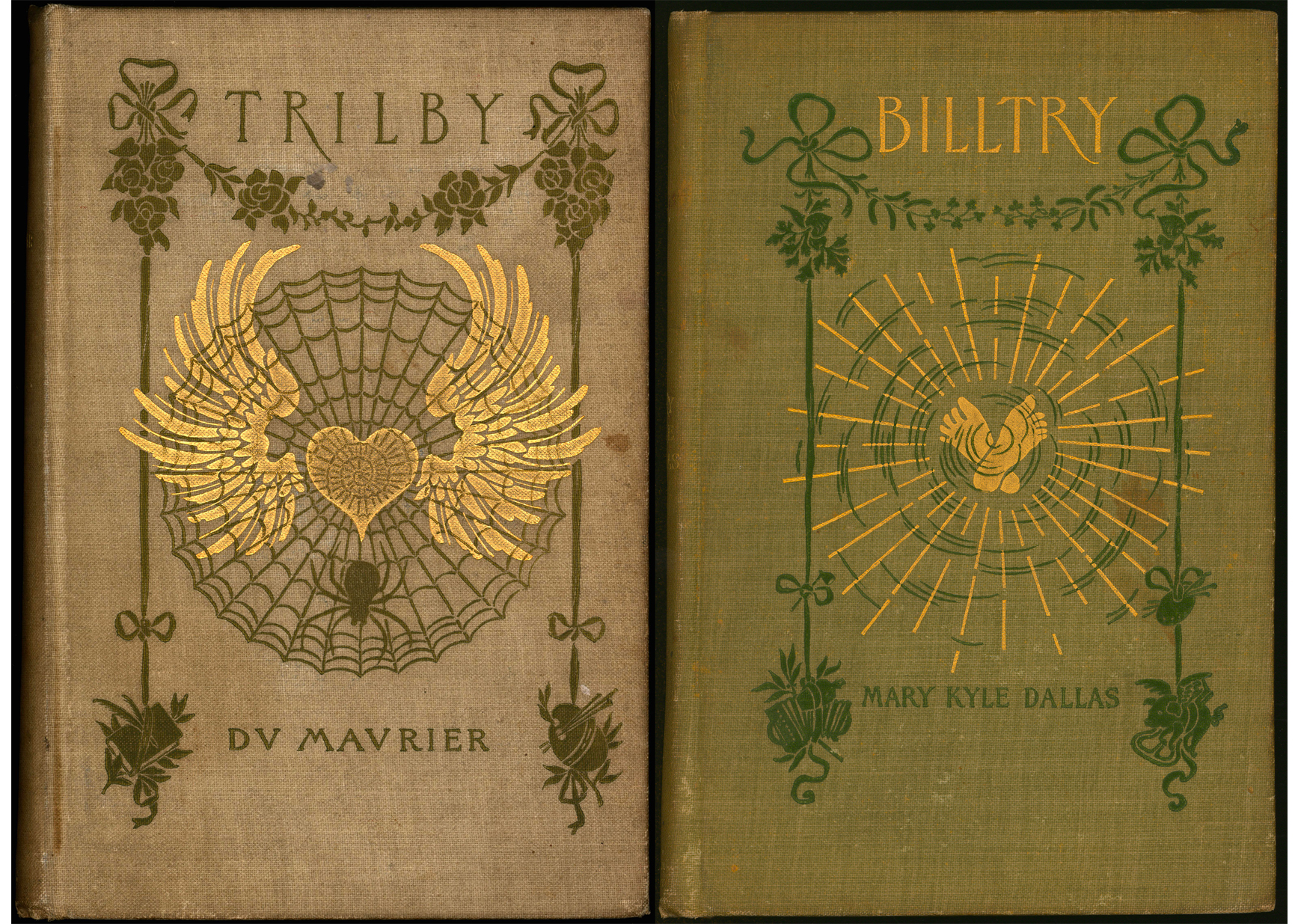

Photograph of John Sloan as Twillbe, 1894. John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Left: Trilby, by George du Maurier (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Right: Billtry, by Mary Kyle Dallas (New York: The Merriam Company, 1895). Carol Jording Rare Book Acquisition Fund, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

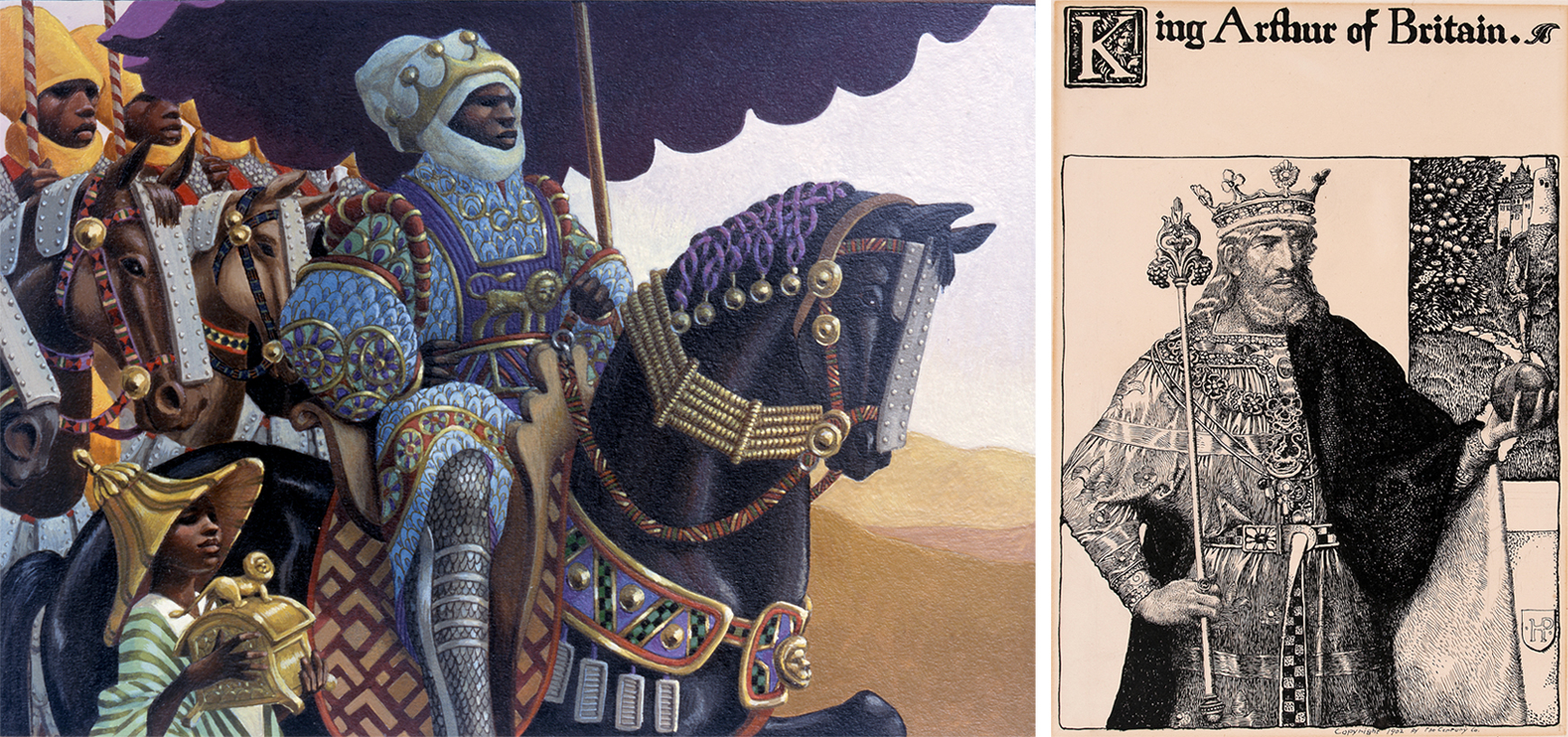

Left: Trilby, by George du Maurier (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895). M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Right: Billtry, by Mary Kyle Dallas (New York: The Merriam Company, 1895). Carol Jording Rare Book Acquisition Fund, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum. Left to right: Mansa Musa King of Mali, 2001. Cover illustration for Mansa Musa: The Lion of Mali, by Khephra Burns, (Gulliver Books, 2001). Diane Dillon (born 1933) and Leo Dillon (1933–2012). Gouache on Bristol board, composition: 6 x 8 1/2 inches, sheet: 10 x 12 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Diane and Leo Dillon. | King Arthur of Britain and decorated initial K with title and design, 1903. Illustration for “The Story of King Arthur and His Knights,” by Howard Pyle, in St. Nicholas, January 1903. Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/8 × 6 3/16 inches, sheet: 11 11/16 × 9 1/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Anne Poole Pyle, 1920.

Left to right: Mansa Musa King of Mali, 2001. Cover illustration for Mansa Musa: The Lion of Mali, by Khephra Burns, (Gulliver Books, 2001). Diane Dillon (born 1933) and Leo Dillon (1933–2012). Gouache on Bristol board, composition: 6 x 8 1/2 inches, sheet: 10 x 12 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Diane and Leo Dillon. | King Arthur of Britain and decorated initial K with title and design, 1903. Illustration for “The Story of King Arthur and His Knights,” by Howard Pyle, in St. Nicholas, January 1903. Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/8 × 6 3/16 inches, sheet: 11 11/16 × 9 1/16 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Anne Poole Pyle, 1920. Left to right: The Ironwood Tree, 2004. Cover illustration for The Ironwood Tree, The Spiderwick Chronicles Book 4, by Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, (Simon & Schuster, 2004). Tony DiTerlizzi (born 1969). Acryla gouache on plate-finish Bristol board, 14 3/4 x 10 3/8 inches, frame: 23 7/8 x 19 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Spiderwick Chronicles © Tony DiTerlizzi & Holly Black. | The Lady of Ye Lake and decorated initial T with title and design, 1903 from The Story of King Arthur and His Knights, by Howard Pyle (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903). Howard Pyle (American illustrator, 1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/16 × 6 1/4 inches, sheet: 14 5/8 × 11 1/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912.

Left to right: The Ironwood Tree, 2004. Cover illustration for The Ironwood Tree, The Spiderwick Chronicles Book 4, by Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, (Simon & Schuster, 2004). Tony DiTerlizzi (born 1969). Acryla gouache on plate-finish Bristol board, 14 3/4 x 10 3/8 inches, frame: 23 7/8 x 19 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Spiderwick Chronicles © Tony DiTerlizzi & Holly Black. | The Lady of Ye Lake and decorated initial T with title and design, 1903 from The Story of King Arthur and His Knights, by Howard Pyle (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903). Howard Pyle (American illustrator, 1853–1911). Ink and graphite on illustration board, composition: 9 1/16 × 6 1/4 inches, sheet: 14 5/8 × 11 1/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912. Left to right:

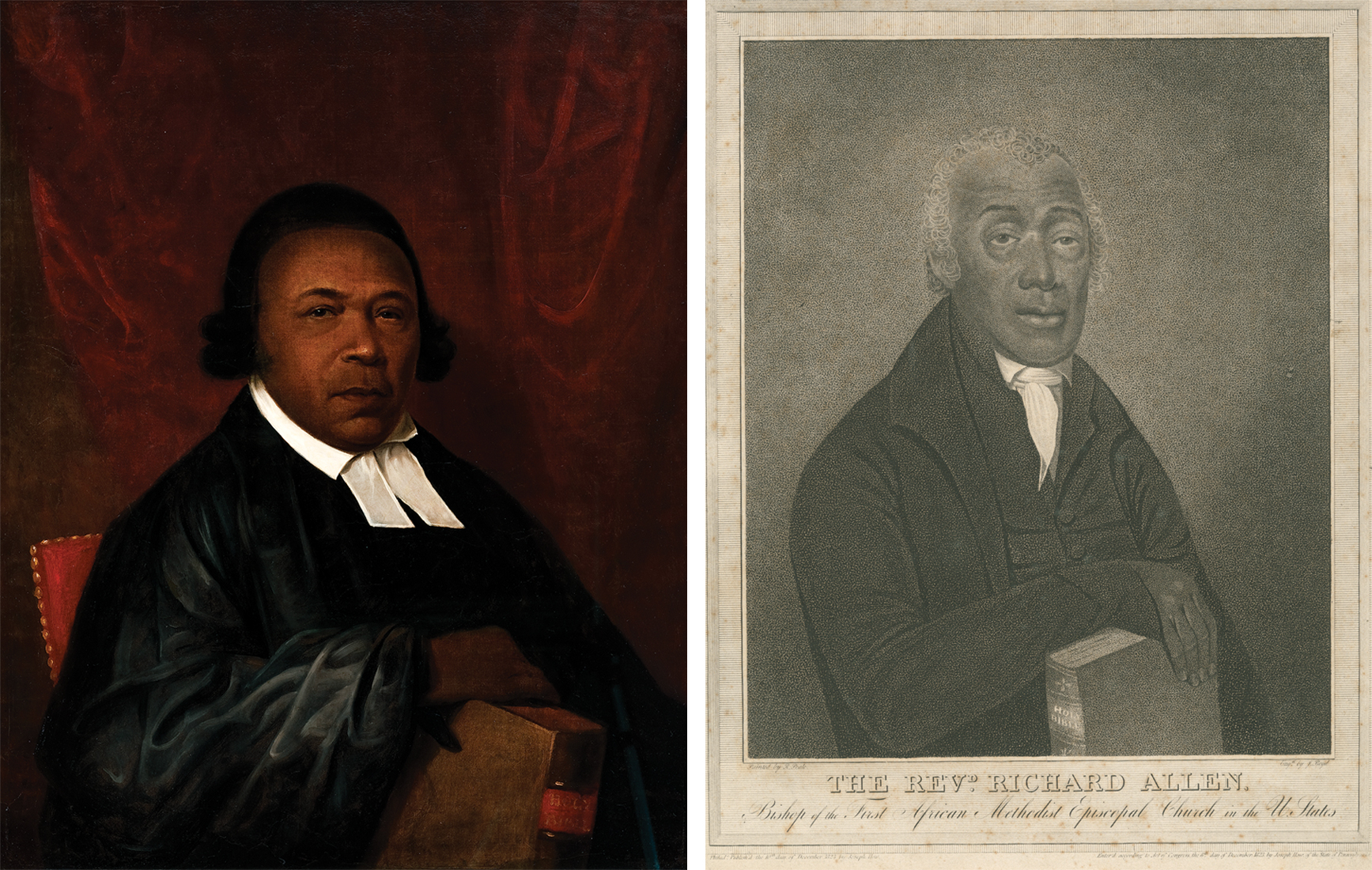

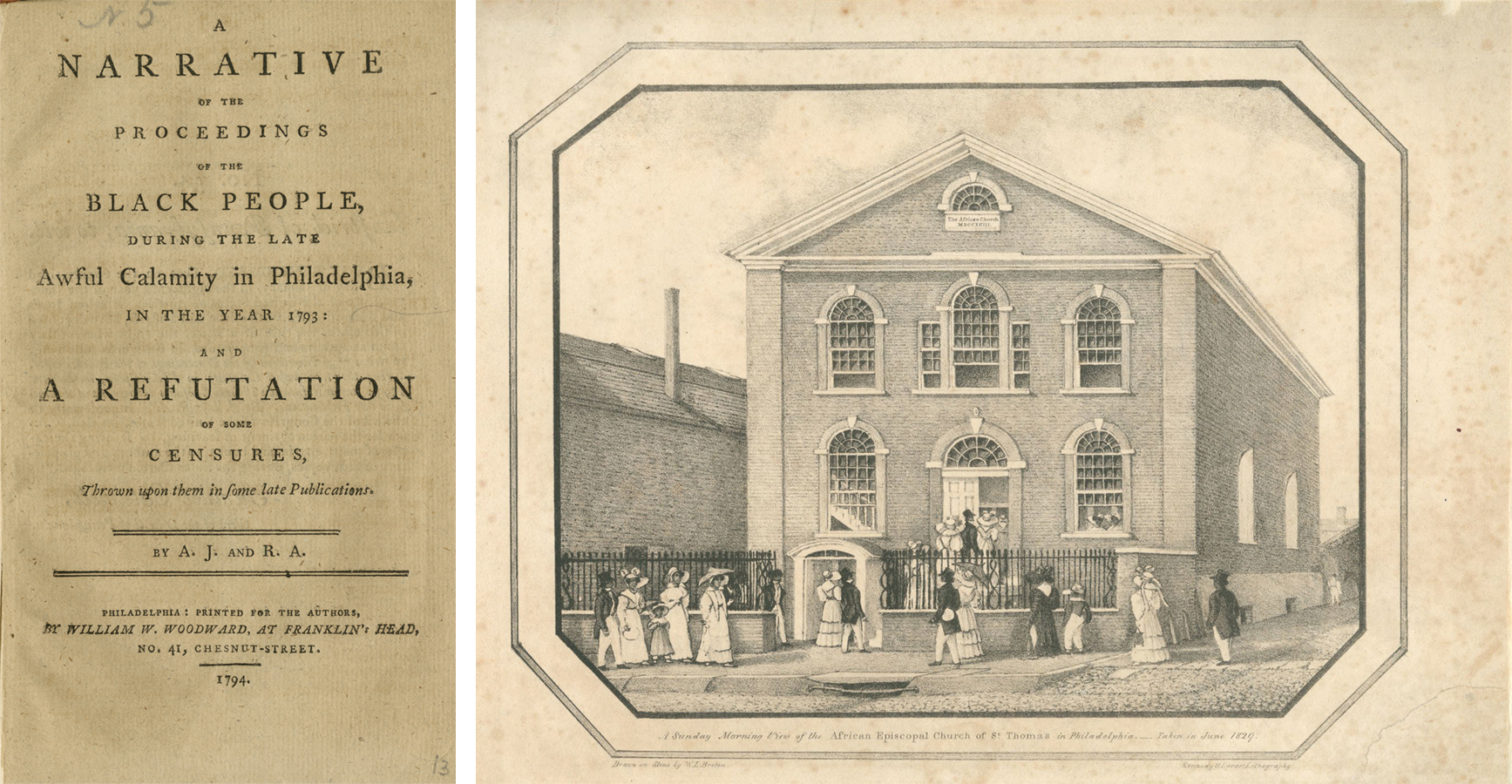

Left to right:  Left to right: Title Page, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, 1794. Absalom Jones (1746–1818) and Richard Allen (1760–1831). Library Company of Philadelphia. A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, 1829. Kennedy & Lucas from a drawing by W. L. Breton (c. 1733–1859). Lithograph, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Left to right: Title Page, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, 1794. Absalom Jones (1746–1818) and Richard Allen (1760–1831). Library Company of Philadelphia. A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, 1829. Kennedy & Lucas from a drawing by W. L. Breton (c. 1733–1859). Lithograph, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

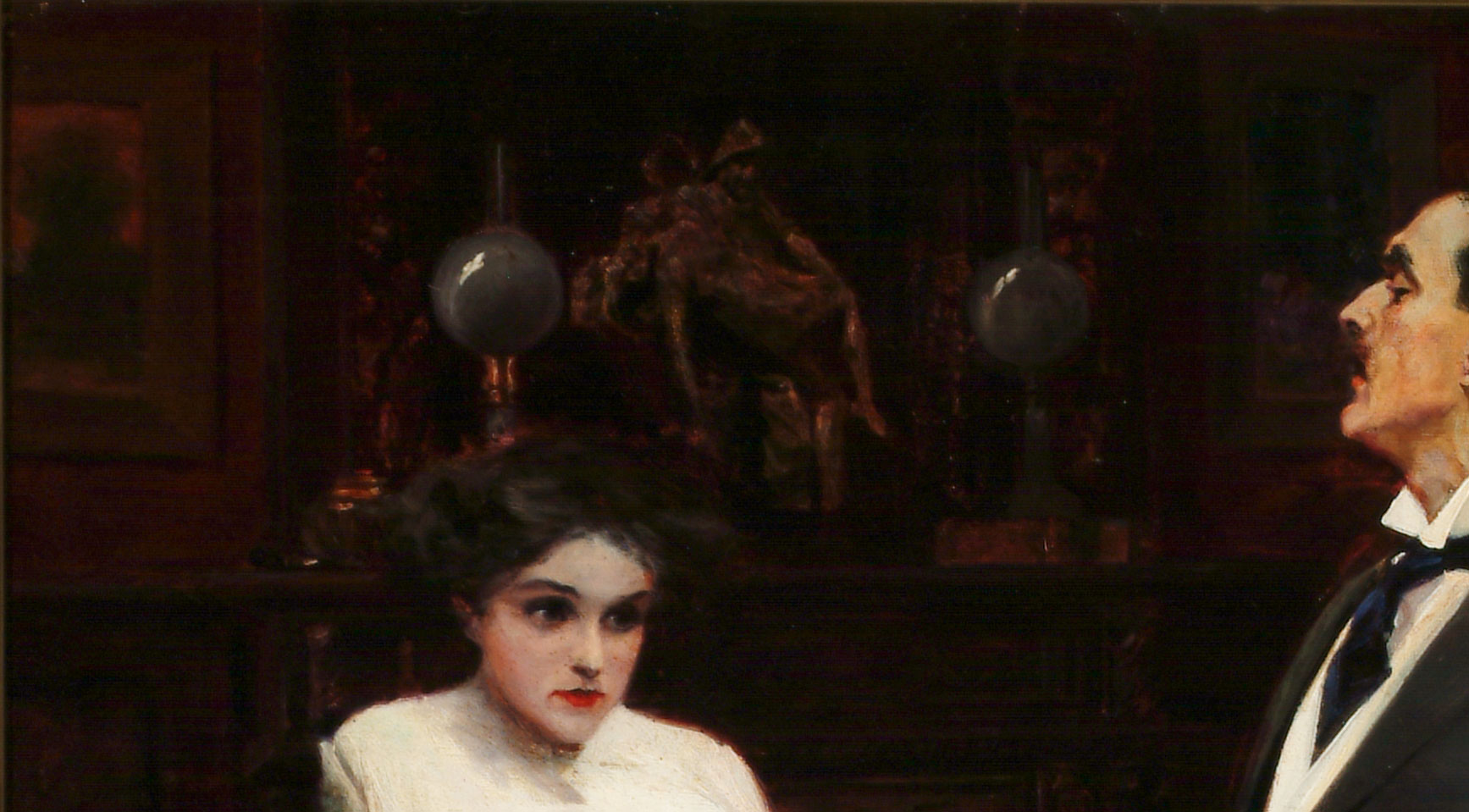

Facing each other at last, the girl white, shaking, her eyes aflame (detail), 1909.

Facing each other at last, the girl white, shaking, her eyes aflame (detail), 1909. Saved, 1887. Adolf Brütt.

Saved, 1887. Adolf Brütt.

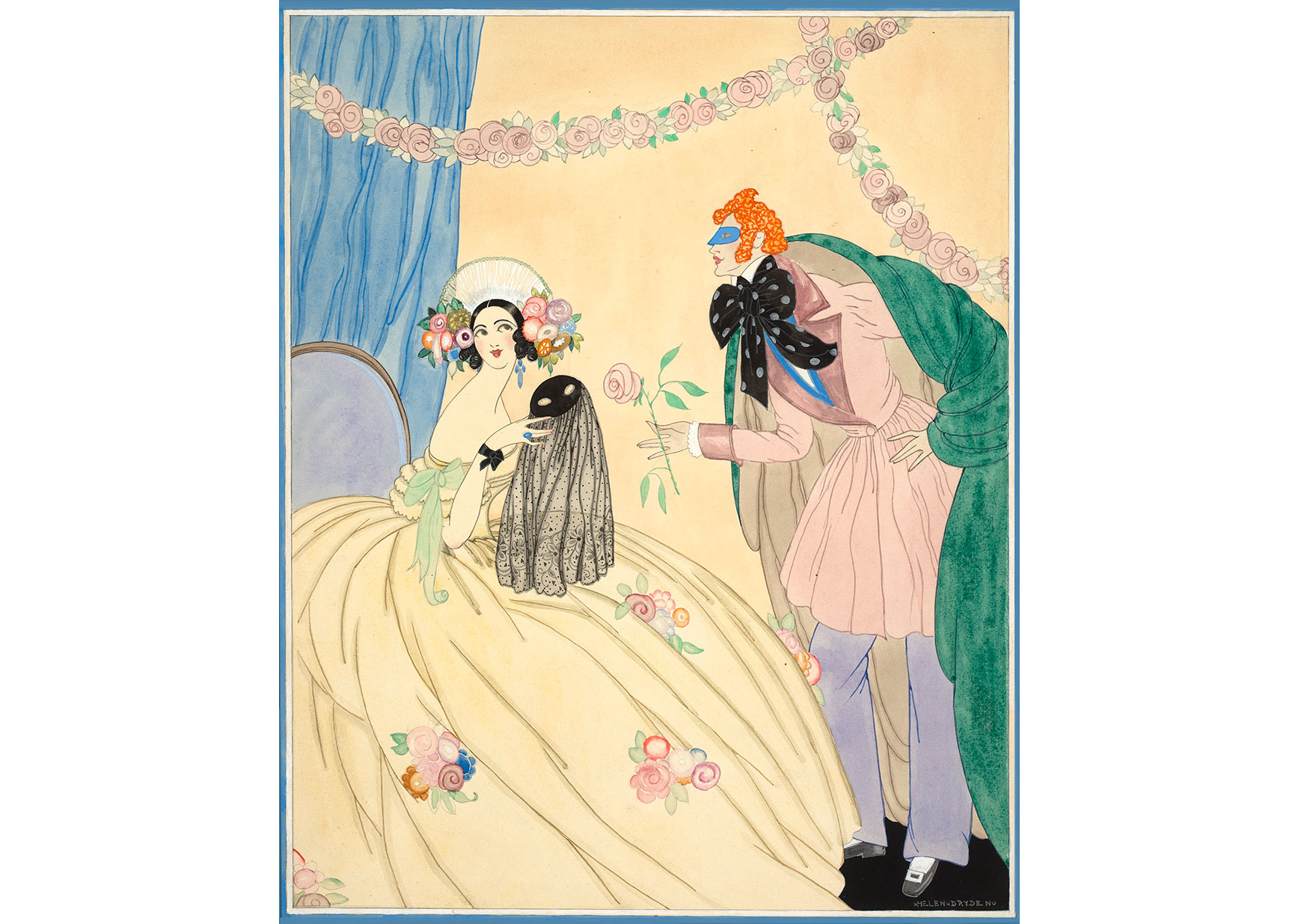

Above: Cover for Vogue, December 15, 1922. Helen Dryden (1882–1981). Gouache, ink, and watercolor on paper, 19 × 15 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 1992.

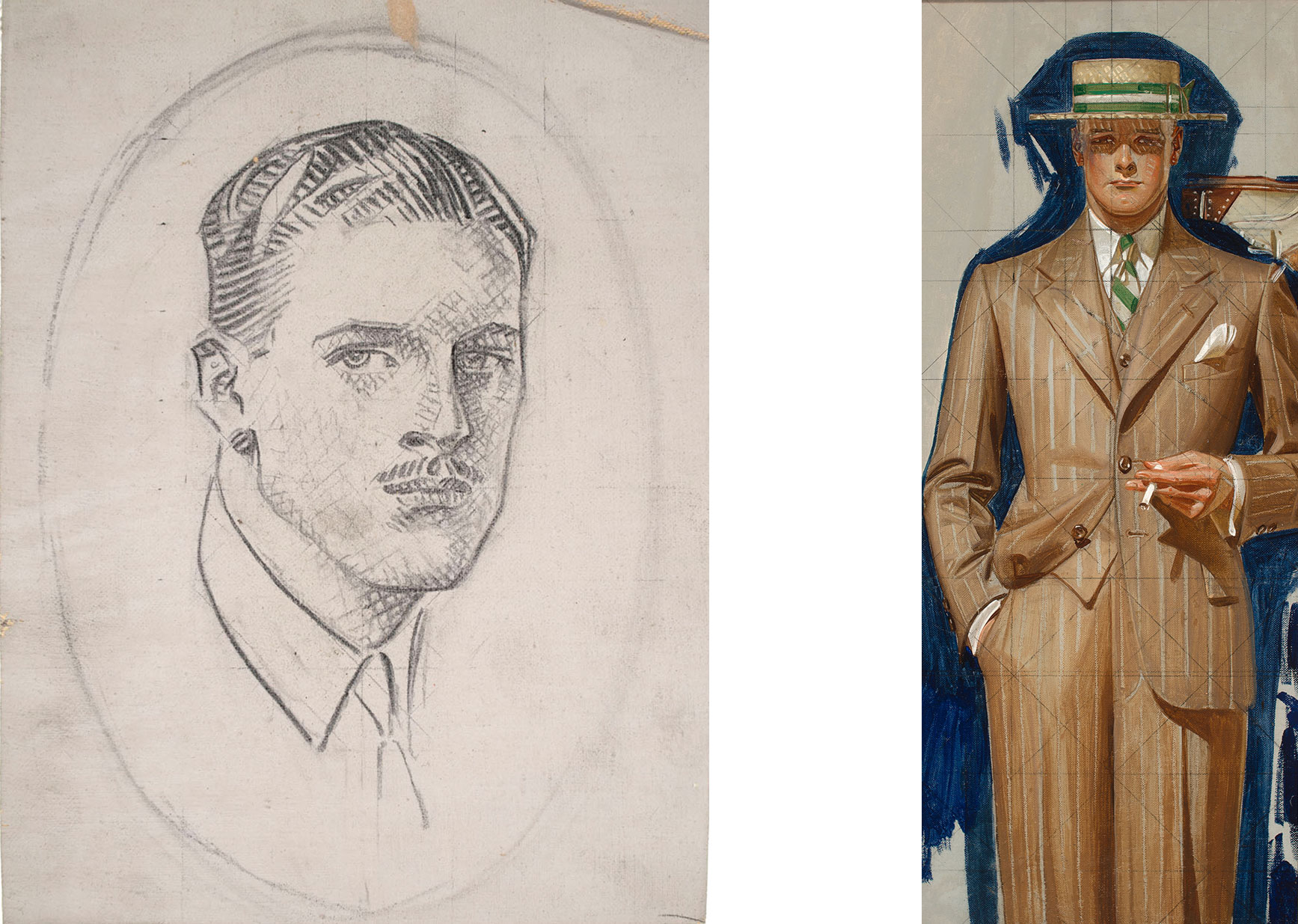

Above: Cover for Vogue, December 15, 1922. Helen Dryden (1882–1981). Gouache, ink, and watercolor on paper, 19 × 15 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 1992. Above, left to right: Portrait Head (Possible Study for Arrow Collar Advertisement), c. 1925. J.C. Leyendecker (1874–1951). Graphite on coated canvas, 10 3/8 x 7 5/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1984; Accessioned, 2020. | Figure Study for a Kuppenheimer Advertisement, 1929. J.C. Leyendecker (1874–1951), Oil on (linen) canvas, 22 x 9 1/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2016.

Above, left to right: Portrait Head (Possible Study for Arrow Collar Advertisement), c. 1925. J.C. Leyendecker (1874–1951). Graphite on coated canvas, 10 3/8 x 7 5/8 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1984; Accessioned, 2020. | Figure Study for a Kuppenheimer Advertisement, 1929. J.C. Leyendecker (1874–1951), Oil on (linen) canvas, 22 x 9 1/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2016. The Bouquet, 1949. Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–1999). Oil on Masonite, 23 3/4 × 17 3/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2018 © Estate of Hughie Lee-Smith / VAGA for ARS, New York, NY.

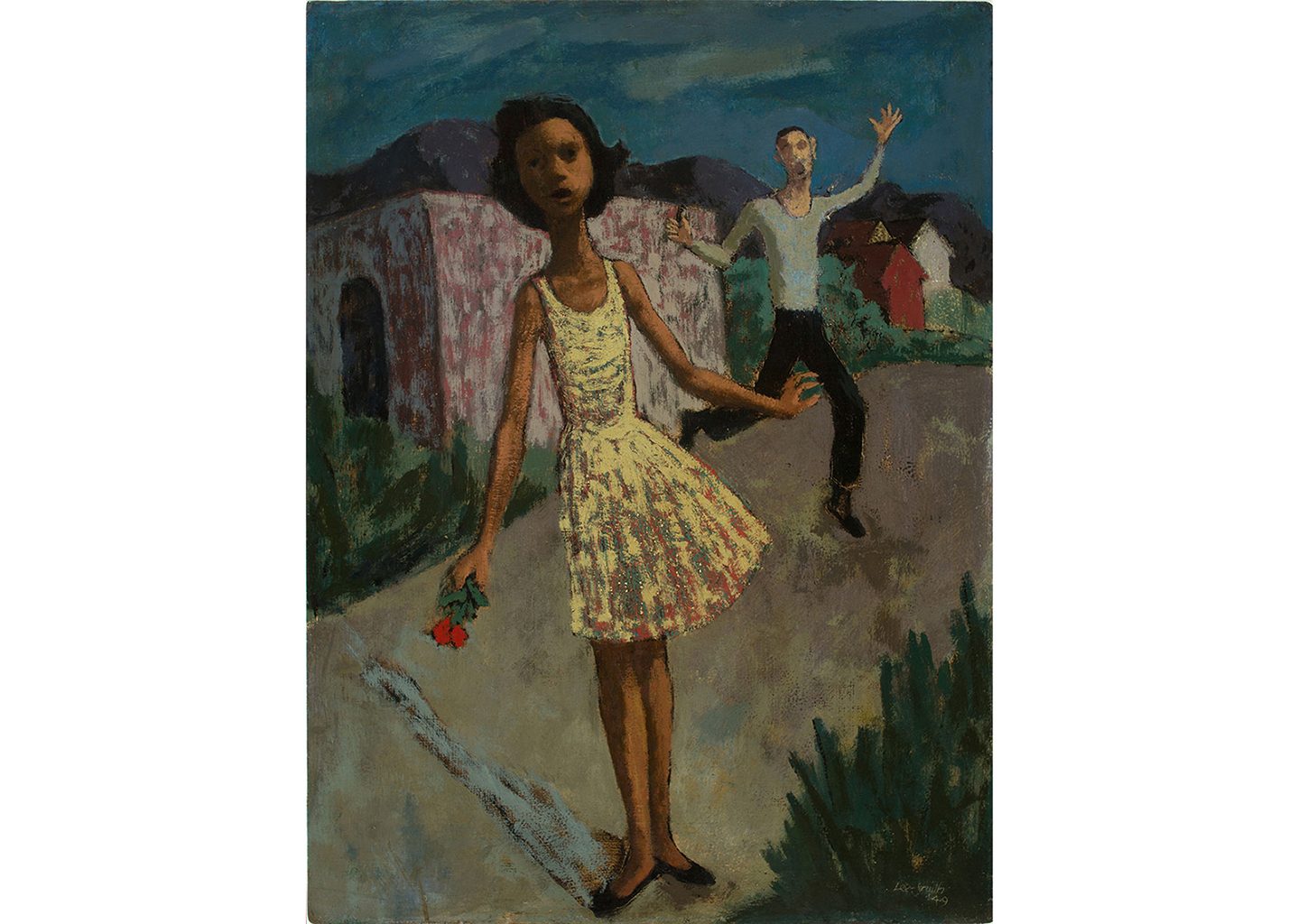

The Bouquet, 1949. Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–1999). Oil on Masonite, 23 3/4 × 17 3/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2018 © Estate of Hughie Lee-Smith / VAGA for ARS, New York, NY.  Above, left to right: Cheadle Royal Hospital Chapel, c. 1920. Cheadle Civic Society Archives. | The Arming of a Knight and Glorious Gwendolen’s Golden Hair, 1856-1857. William Morris (1834-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Painted deal, leather, and nails, Delaware Art Museum, Acquired through the Bequest of Doris Wright Anderson and through the F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 1997.

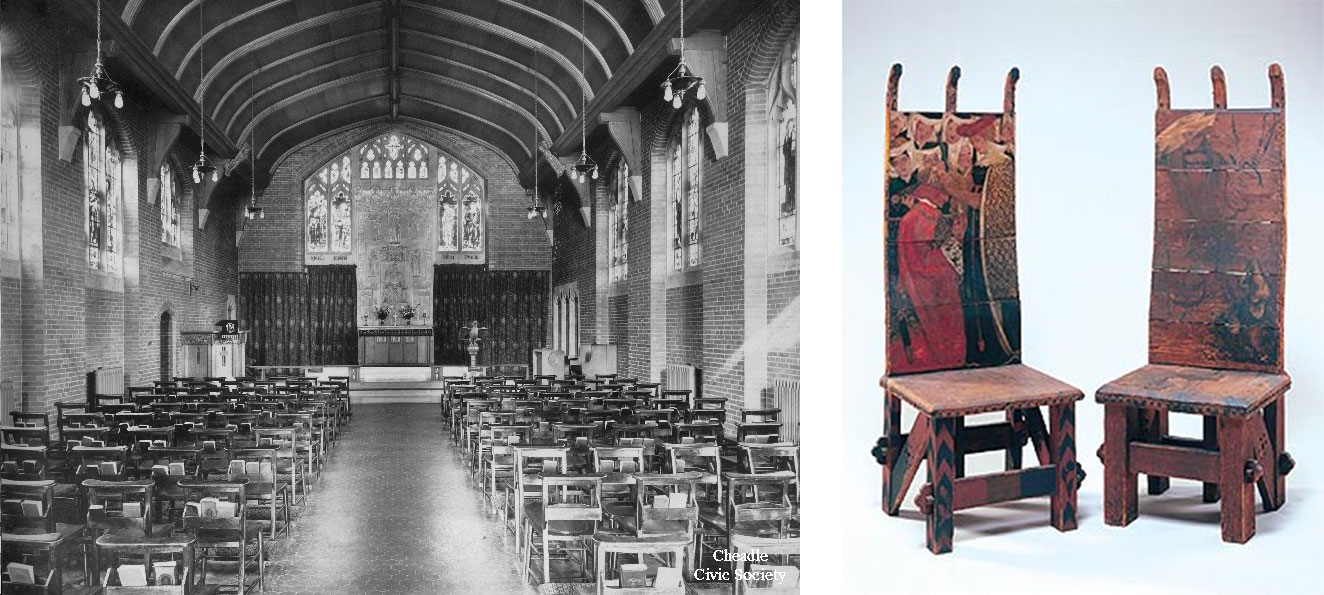

Above, left to right: Cheadle Royal Hospital Chapel, c. 1920. Cheadle Civic Society Archives. | The Arming of a Knight and Glorious Gwendolen’s Golden Hair, 1856-1857. William Morris (1834-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Painted deal, leather, and nails, Delaware Art Museum, Acquired through the Bequest of Doris Wright Anderson and through the F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund, 1997. Sound the deep waters, 2019. Angela Fraleigh (born 1976). Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 × 198 inches. Courtesy of the artist. ©Angela Fraleigh. Photograph by Kenek Photography.

Sound the deep waters, 2019. Angela Fraleigh (born 1976). Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 × 198 inches. Courtesy of the artist. ©Angela Fraleigh. Photograph by Kenek Photography. Our world swells like dawn, when the sun licks the water, 2019. Angela Fraleigh (born 1976). Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 × 198 inches. Courtesy of the artist. ©Angela Fraleigh. Photograph by Kenek Photography.

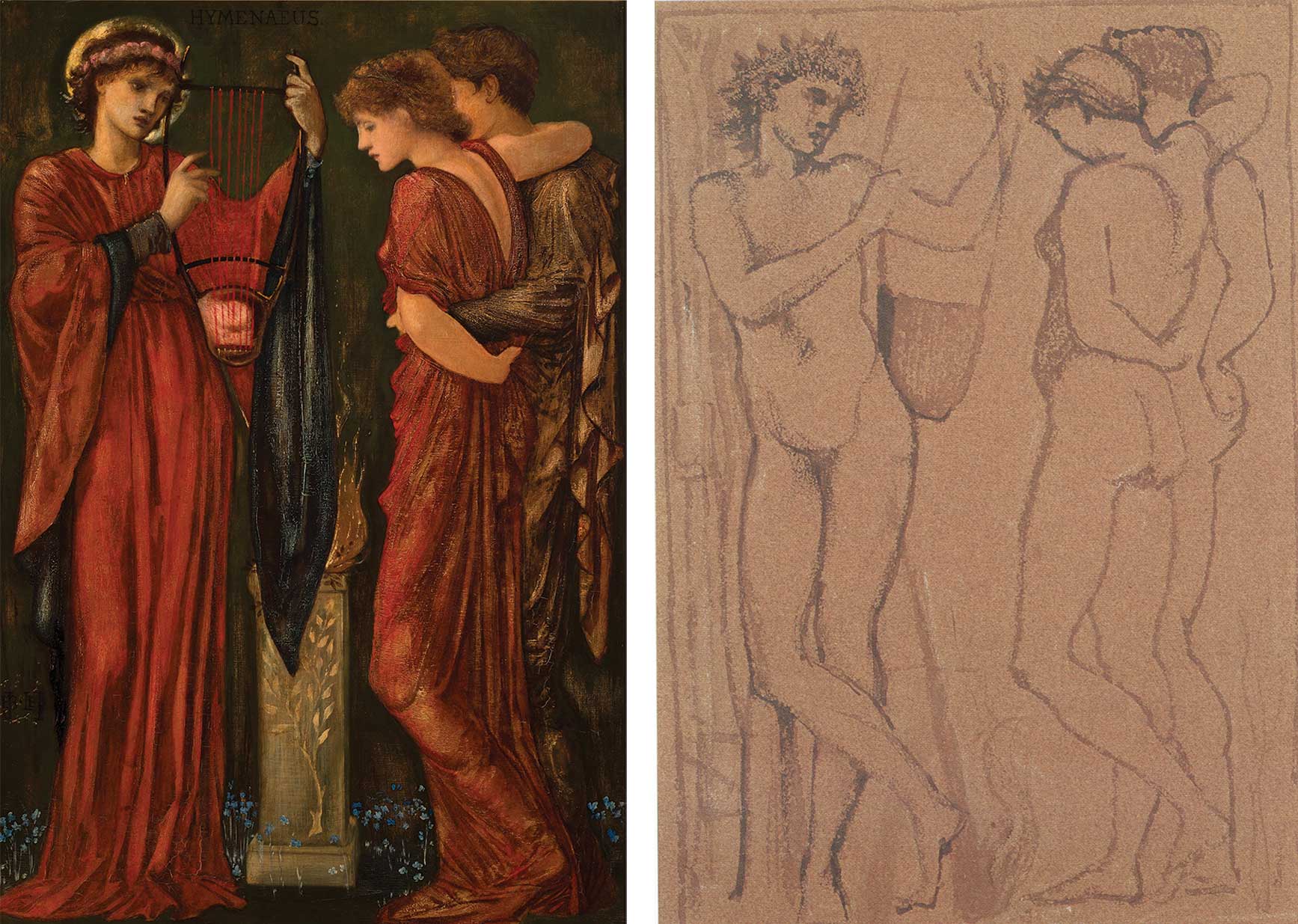

Our world swells like dawn, when the sun licks the water, 2019. Angela Fraleigh (born 1976). Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 × 198 inches. Courtesy of the artist. ©Angela Fraleigh. Photograph by Kenek Photography. ILL. #2 Hymenaeus, 1869. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). Oil paint over gold leaf on panel, 32 1/4 x 21 1/2 inches, frame: 36 x 49 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. ILL. #3 Study for Hymenaeus, undated. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). Charcoal and wash on brown paper. Private collection.

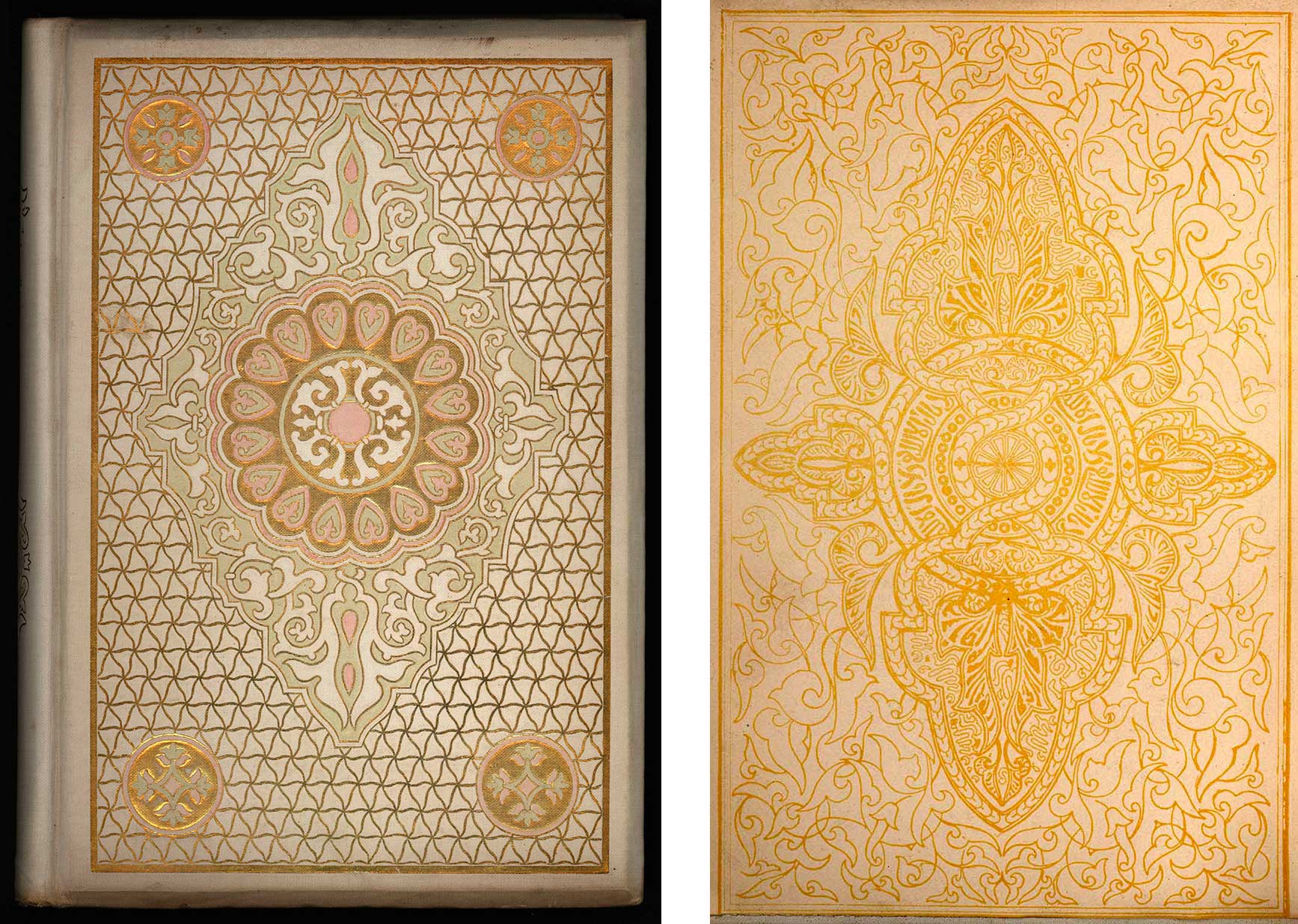

ILL. #2 Hymenaeus, 1869. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). Oil paint over gold leaf on panel, 32 1/4 x 21 1/2 inches, frame: 36 x 49 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935. ILL. #3 Study for Hymenaeus, undated. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). Charcoal and wash on brown paper. Private collection. Above, left to right: Chronicle of the conquest of Granada by Washington Irving, cover design by Alice C. Morse (New York: Putnam, 1893) M.G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. | Endpaper possibly designed by Alice C. Morse from The Alhambra by Washington Irving (New York: Putnam, 1892) Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives.

Above, left to right: Chronicle of the conquest of Granada by Washington Irving, cover design by Alice C. Morse (New York: Putnam, 1893) M.G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. | Endpaper possibly designed by Alice C. Morse from The Alhambra by Washington Irving (New York: Putnam, 1892) Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives. Above, left to right: Just like moons and like suns, still I’ll rise (Fanny Eaton to Maya Angelou), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel. | The ocean could not be swept back with a broom. The truth was out and it illuminated the world. (Margaret Sanger to Madame Restell), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in ceramic vessel.

Above, left to right: Just like moons and like suns, still I’ll rise (Fanny Eaton to Maya Angelou), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel. | The ocean could not be swept back with a broom. The truth was out and it illuminated the world. (Margaret Sanger to Madame Restell), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in ceramic vessel. Above: Daughter of the Sun (Circe’s Garden), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel.

Above: Daughter of the Sun (Circe’s Garden), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel. Above, left to right: The stars tell all their secrets to the flowers, and, if we only knew how to look around us, we should not need to look above. (Margaret Fuller to Simone de Beauvoir), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in ceramic vessel. | Stained with moonlight, nurtured by the stars (Lord Alfred Douglas to Oscar Wilde), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel.

Above, left to right: The stars tell all their secrets to the flowers, and, if we only knew how to look around us, we should not need to look above. (Margaret Fuller to Simone de Beauvoir), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in ceramic vessel. | Stained with moonlight, nurtured by the stars (Lord Alfred Douglas to Oscar Wilde), 2019. Cold porcelain, wire, oil paint, and pastel in glass vessel. Above, left to right: Untitled, 1980s. Mitch Lyons (1938-2018). Clay monoprint, sheet: 33 3/4 × 34 3/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 2012. © Estate of Mitch Lyons. | Untitled pot, not dated. Mitch Lyons (1938-2018). Ceramic, 10 3/8 x 6 ½ inches. Collection of the Estate of Mitch Lyons. © Estate of Mitch Lyons. Photograph by Carson Zullinger.

Above, left to right: Untitled, 1980s. Mitch Lyons (1938-2018). Clay monoprint, sheet: 33 3/4 × 34 3/4 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 2012. © Estate of Mitch Lyons. | Untitled pot, not dated. Mitch Lyons (1938-2018). Ceramic, 10 3/8 x 6 ½ inches. Collection of the Estate of Mitch Lyons. © Estate of Mitch Lyons. Photograph by Carson Zullinger. Fig. 2. Landscape Box (closed), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

Fig. 2. Landscape Box (closed), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong. Fig. 3. Landscape Box (open) (detail), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong.

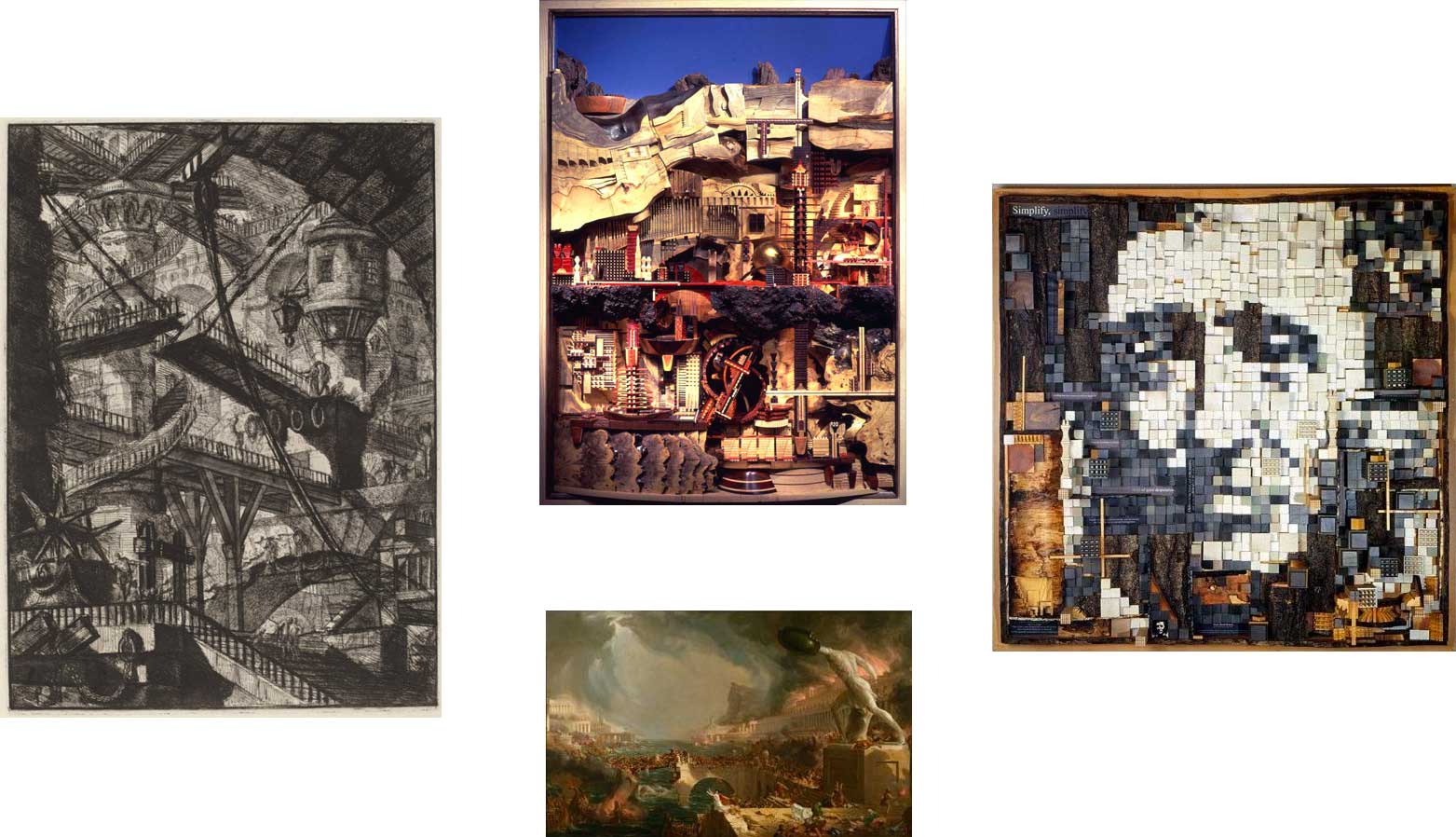

Fig. 3. Landscape Box (open) (detail), c. 1988. Po Shun Leong (born 1941). Cherry burl, wenge, mahogany, and Hawaiian koa woods with built-in lamp, 19 × 21 5/8 × 6 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Nancy and Joe Miller, 1998. © Po Shun Leong. Clockwise, from left: Fig. 4. The Drawbridge, from Carceri, 1780s. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Etching, engraving, scratching, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. Fig. 5. Mesa Verde, 1994. Po Shun Leong. Buckeye burl woods, 55 x 40 x 9 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 7. Portrait collage of Henry David Thoreau, 2001. Po Shun Leong. Wood, 60 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 6. The Course of Empire: Destruction, 1836. Thomas Cole. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 63 1/2 inches. New York Historical Society, Gift of The New York Gallery of the Fine Arts.

Clockwise, from left: Fig. 4. The Drawbridge, from Carceri, 1780s. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Etching, engraving, scratching, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. Fig. 5. Mesa Verde, 1994. Po Shun Leong. Buckeye burl woods, 55 x 40 x 9 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 7. Portrait collage of Henry David Thoreau, 2001. Po Shun Leong. Wood, 60 inches. Image from Po Shun Leong. Fig. 6. The Course of Empire: Destruction, 1836. Thomas Cole. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 63 1/2 inches. New York Historical Society, Gift of The New York Gallery of the Fine Arts.